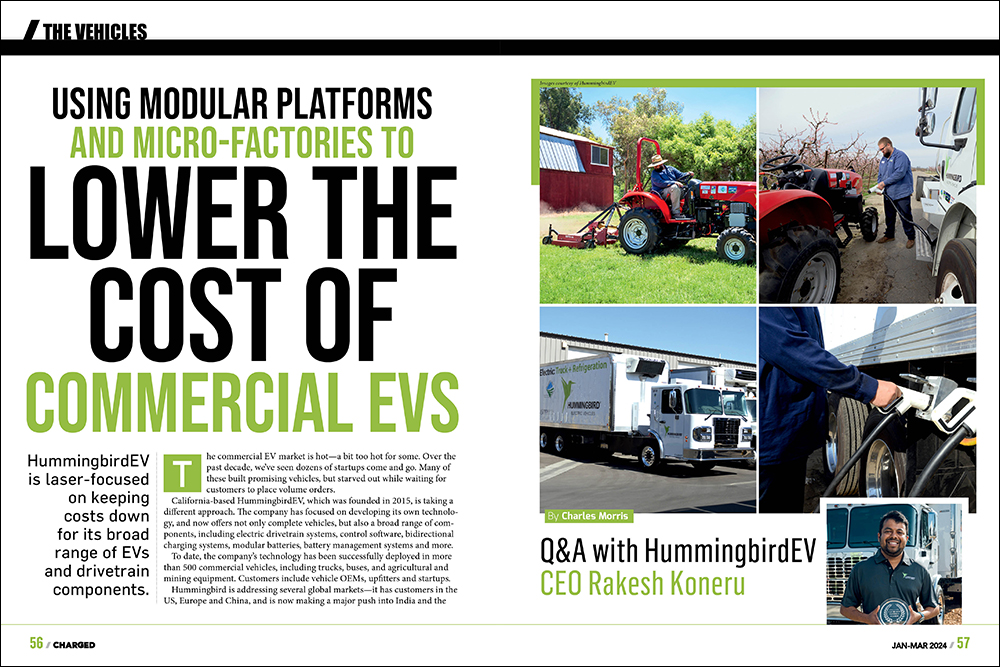

Q&A with HummingbirdEV CEO Rakesh Koneru.

The commercial EV market is hot—a bit too hot for some. Over the past decade, we’ve seen dozens of startups come and go. Many of these built promising vehicles, but starved out while waiting for customers to place volume orders.

California-based HummingbirdEV, which was founded in 2015, is taking a different approach. The company has focused on developing its own technology, and now offers not only complete vehicles, but also a broad range of components, including electric drivetrain systems, control software, bidirectional charging systems, modular batteries, battery management systems and more.

To date, the company’s technology has been successfully deployed in more than 500 commercial vehicles, including trucks, buses, and agricultural and mining equipment. Customers include vehicle OEMs, upfitters and startups.

Hummingbird is addressing several global markets—it has customers in the US, Europe and China, and is now making a major push into India and the GCC (Persian Gulf) region. The company is laser-focused on keeping costs down, and a key part of that strategy involves setting up micro-factories to serve specific customers, and building local supply chains.

Charged spoke with HummingbirdEV CEO Rakesh Koneru about his company’s plans for rapid expansion, and how it has avoided the pitfalls that have trapped other commercial EV players.

Charged: What stage of business development would you say you’re in at this point?

Rakesh Koneru: From a customer traction perspective, we’ve deliberately kept a low profile while we developed our technology. It’s important to know that we’re coming at this with upwards of 14 years of experience in the commercial vehicle electrification space. We’ve retrofitted European chassis, Indian gliders, and US-made OEM trucks. We have seen all the pitfalls, and we’ve tried to address these technological challenges in terms of commercialization. That takes time and focus. How do you build a vertically integrated modular vehicle platform that can not only fit the North American market, but can also scale up to growing markets like India? How do you take a $200,000 truck and make it a $40,000 truck? That’s been the biggest challenge. We believed in the technology, and we’ve focused on building that tech, and that’s what the last seven years were all about. We’re also growing, and want to build up the team to get to mass production in the next three to five years.

Charged: We’ve seen so many commercial EV makers come and go. It sounds like you’re taking a different approach than most of the companies that have addressed this space.

Rakesh Koneru: That’s true. We believe technology and mass adoption have to be done in a different way right now. Everyone’s doing electric, and whether it’s a traditional OEM or a new company, everyone has their own set of problems. The traditional guys come in from a compliance standpoint, not from a standpoint of acquiring the market, so there is a high initial cost to building and selling the product, which, to a regular user and a consumer, is well out of reach. On the flip side, the new-age companies, they’ve gone through SPACs in the rush to raise money, and companies went public too early, burning cash too fast, misinterpreting the demand and not having the right technology. They’re getting into the market with the wrong technology and high capital investment costs.

The new-age companies, they’ve gone through SPACs in the rush to raise money, and companies went public too early, burning cash too fast, misinterpreting the demand and not having the right technology.

I think everyone misinterpreted the demand to be a curve similar to the car segment, but it’s not. The commercial market is a bit unique and niche, and they’re very traditional too. How do you convince someone who’s been driving diesel all their life to go electric if you have a fixed range and a weight compromise, and by the way, you have to pay double the cost?

There are infrastructure limitations as well. When it comes to commercial EVs, electric power upgrades typically take about 18 to 24 months. And that’s with a handful of vehicles. Now, how do you want to do your whole fleet electrification, and how do you reduce the infrastructure deployment time? How do you increase grid reliability, and how do you manage the peak hours?

Charged: All issues that we’ve heard about from a lot of companies. Can you give me some specific examples of how you got around those challenges?

Rakesh Koneru: For us, technology comes first right now. Cars, to a certain extent, in the next five years, everything’s going to be pretty standardized. Whether it’s a Tesla or a Volkswagen, you’ll get to a point where everyone uses more or less a certain battery pack to drive a certain range. In the commercial vehicle segment, that’s not going to work.

If you take a Class 6, from a walk-in to a box truck to a refrigerated truck to a port vehicle, a tractor, every application is unique, and going in with a traditional mindset of a standard-size battery pack, it’s not going to work.

If you look at the new-age companies and the traditional OEMs, they’re still stuck with the diesel thought process: I’ll give you one or two fixed battery pack combinations and it’s up to you to figure it out. But trucks are used in a gazillion different applications. If you take a Class 6, from a walk-in to a box truck to a refrigerated truck to a port vehicle, a tractor, every application is unique, and going in with a traditional mindset of a standard-size battery pack, it’s not going to work. So, what Hummingbird is trying to accomplish is to bring modularity into a vehicle platform, where on the same production line, we can have combinations of vehicles. Whether it’s a bigger or smaller battery pack size, the type of batteries, the type of motors, you need to have sort of a Lego block design where you can add a thing or delete a thing on the same production line.

That’s from the technology side. From the manufacturing side, we’re trying to localize it. We’re going with a micro-factory approach because our systems are very unconventionally built—we do not need a typical thought process of how factories look. We will not be requiring huge real estate. We will not be getting into foundries and welding and heat treatments. A lot of stuff is minimalized in our case, and also cleaner in how we produce the vehicles. We’re approaching it from both the tech and the manufacturing standpoint to be modular, to enable and deploy for any vehicle application.

We’re going with a micro-factory approach because our systems are very unconventionally built—we do not need a typical thought process of how factories look.

We are trying to be in that end-to-end mobility space. What I mean by that is we look at an application. For example, in India we’re working with one of the biggest e-commerce companies. We worked with the customer to define their duty cycle, and we’ve built a vehicle around that.

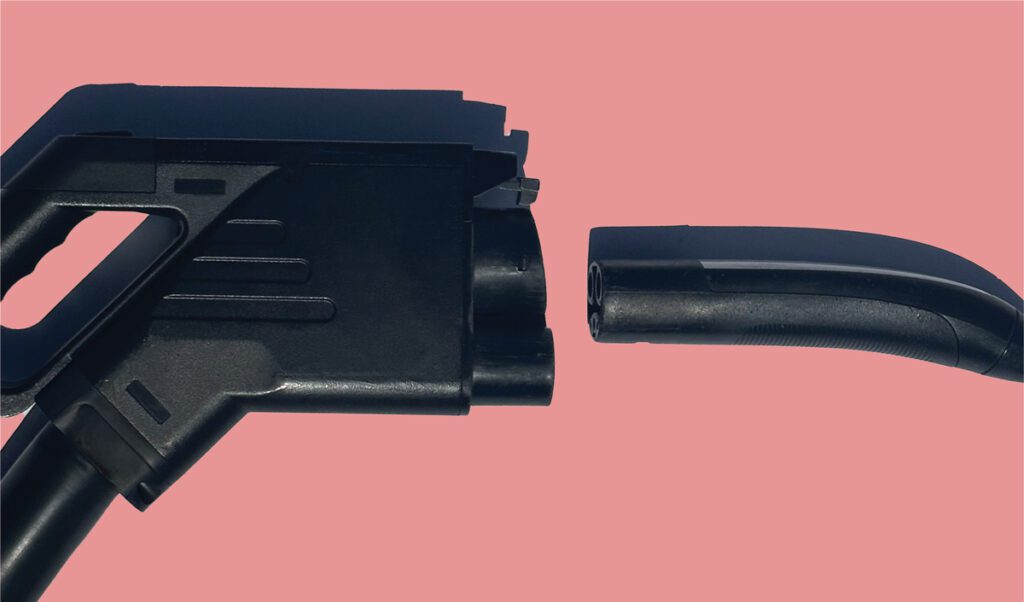

We have a lot of perks from our tech—we have onboard bidirectional charging systems, which enables the customer to do fast onboard charging, which is the first of its kind in the commercial vehicle space. And we also have a fast vehicle-to-vehicle DC charging protocol that is unique to us. We’re looking at an end-to-end, plug-and-play modular vehicle platform that can be built on a low CapEx.

Charged: So, you would set up a micro-production facility for a particular customer?

Rakesh Koneru: Be where the customer is, and that helps us in multiple different ways, from a geopolitical standpoint to knowing the customer better in the local market. And from an investment standpoint too, to diversify and get local investment rather than raising from one big investor.

Charged: Are most of your customers or potential customers vehicle OEMs, or are they mostly end users like fleet operators?

Rakesh Koneru: They’re mostly end users at this point. We are doing a few things to get into a strategic partnership with OEMs, but I think we’re a bit too early for that. We just have to go with the traction that we have with the end users and we’ll see what comes out of it.

Charged: Tell me more about this vehicle-to-vehicle charging system. We hear a lot about vehicle-to-grid and vehicle-to-building, but what’s the application for vehicle-to-vehicle charging?

Rakesh Koneru: Vehicle-to-vehicle is nothing new when you look at it from a naming convention standpoint, but how we do it is unique. In the market today, you have two different types of vehicle-to-vehicle technologies. One is like a Rivian or a Ford F-150 Lightning that has an onboard charger that charges another vehicle using Level 2 AC charging.

The second application is that you have a diesel truck that has all the EV components in the back of the truck, and that does vehicle-to-vehicle charging using a DC power source. So, you necessarily have two technologies right now—what we’re trying to do is bring in the third. We are building a truck, which is electric and can do V2V at DC power levels. We’re trying to move away from slow charging AC V2V into fast CCS V2V charging. And at the same time, we’re not loading batteries and power electronics in the back, but rather the vehicle itself moves the energy from its battery to the other side.

As an example of the type of end customer that would benefit from V2V tech, say today you run out of gas and you’re a AAA member. You call AAA, they’ll come and bring you a gallon of gas. Now, how do we give you a gallon worth of electricity for that first 25 to 30 miles so you can get home or go to a charging station? How do we do it fast? That is a unique technology that we’re trying to bring into the market. We demonstrated this about four years back on a farm where we were charging electric tractors. You can find a few videos on our company web site.

Charged: You sell a lot of different components: drivetrains, batteries, chargers. Do you manufacture most of that stuff in-house or do you get some of it from suppliers?

Rakesh Koneru: It’s designed from our side, and a lot of it we work with contract manufacturing—a combination of our strategic suppliers and our Tier 1 OEM suppliers where we buy some outside components with our design tweaks in.

Charged: Is that going to be more localized also? For example, you have a customer in India—are you going to build a network of component suppliers there in India, so you don’t have to ship things around the world?

Rakesh Koneru: That’s right. For us it’s just the cost. At the end of the day, we want to be as close to a diesel cost as possible in the next five years without incentives. Now, how do we go there? With all that said, suppliers in India are also there. For example, Dana is in the US, Dana is in India, Dana is there globally. We have local players who know the local markets. How do I take my base technology and work with the local partners in the various regions to get to the price point?

There’s going to be a certain level of raw material that still has to be sourced internationally among all our entities, but our focus is to get at least 75 to 80% of the cost in the local market.

However, there are certain technologies—batteries for example—which cannot be done in India. To a certain extent, the batteries that we use on our trucks in North America today also do not have a local supplier because we’re not using cylindrical cells, we’re using a prismatic cell. There’s going to be a certain level of raw material that still has to be sourced internationally among all our entities, but our focus is to get at least 75 to 80% of the cost in the local market. That’s from chassis, axle, suspension, battery assemblies, building local components. How do we create that local cluster around our micro-factories?

Charged: Is it mostly just batteries that come from China?

Rakesh Koneru: At this point the only thing we depend on China for is battery cells. Not the complete pack but just cells. With the exception of that, I would say 90% of what we do is all sourced in the US and probably about 3 to 4% is from the UK and Europe.

Charged: I guess everyone would like to get their batteries from somewhere other than China, but that’s not going to happen overnight. What kind of timeline do you think we’re looking at?

Rakesh Koneru: I don’t know about the consumer side, but for a commercial vehicle application, optimistically I would say the first batteries are probably four to five years out. Mass production is probably seven to ten years out.

Charged: Any new things in the pipeline you’d like to tell us about?

Rakesh Koneru: We have some cool products that we’re trying to unveil with our own skateboard chassis platform in the next couple of months. That’s our first mass go-to-market product. Our current facility today can produce about one truck a month. By the end of this year, we’re trying to get to one truck a day in California. We’re trying to scale it up into both the two other places [India and the UAE].

But unlike the traditional OEMs, we’re not going to get stuck with just selling a truck. We’re trying to open up a lot of revenue-based models. We will sell a complete truck to an end user, but we will also be selling our skateboard architecture to the users, to white-label for say, their own cab application. And we will also sell different layers of our systems—our powertrains, our onboard chargers, whatever it is. We will get into selling components as well. That’s how we see we can get to high volumes quickly. And because we control the whole nine yards, from hardware to software, it enables us to do things in a flexible manner with a reduced time to market. It’s going to be a completely different approach in how we engage with the market when we start this full-scale in the next couple of months.

This article first appeared in Issue 67: January-March 2024 – Subscribe now.