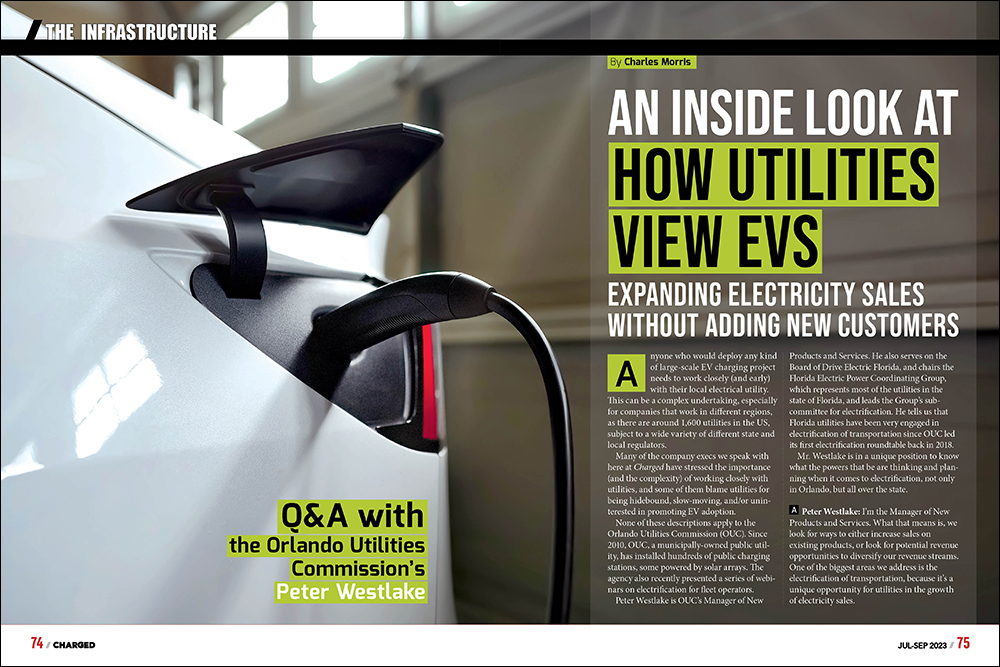

Q&A with the Orlando Utilities Commission’s Peter Westlake.

Anyone who would deploy any kind of large-scale EV charging project needs to work closely (and early) with their local electrical utility. This can be a complex undertaking, especially for companies that work in different regions, as there are around 1,600 utilities in the US, subject to a wide variety of different state and local regulators.

Many of the company execs we speak with here at Charged have stressed the importance (and the complexity) of working closely with utilities, and some of them blame utilities for being hidebound, slow-moving, and/or uninterested in promoting EV adoption.

None of these descriptions apply to the Orlando Utilities Commission (OUC). Since 2010, OUC, a municipally-owned public utility, has installed hundreds of public charging stations, some powered by solar arrays. The agency also recently presented a series of webinars on electrification for fleet operators.

Peter Westlake is OUC’s Manager of New Products and Services. He also serves on the Board of Drive Electric Florida, and chairs the Florida Electric Power Coordinating Group, which represents most of the utilities in the state of Florida, and leads the Group’s subcommittee for electrification. He tells us that Florida utilities have been very engaged in electrification of transportation since OUC led its first electrification roundtable back in 2018.

Mr. Westlake is in a unique position to know what the powers that be are thinking and planning when it comes to electrification, not only in Orlando, but all over the state.

Peter Westlake: I’m the Manager of New Products and Services. What that means is, we look for ways to either increase sales on existing products, or look for potential revenue opportunities to diversify our revenue streams. One of the biggest areas we address is the electrification of transportation, because it’s a unique opportunity for utilities in the growth of electricity sales.

Charged: Can you walk us through how a utility decides to invest in EVs and charging infrastructure?

Peter Westlake: It depends a lot on the structure of the utility. Municipally-owned public utilities and investor-owned utilities have different guardrails as far as what they can and can’t do. For instance, in our jurisdiction, to install electric vehicle infrastructure, we don’t have to obtain approval from the Florida Public Service Commission (PSC), whereas Duke and Florida Power & Light do.

At OUC, we see investing in EVs as an expansion of our service territory by one quarter to one third of a house, if you consider that three to four electric vehicles represent about the same type of load that an additional house might require. As a municipal utility, we’re constrained within our jurisdiction. Supporting EV charging and encouraging ownership of EVs is a unique opportunity for load growth without actually expanding our services to new customers.

To obtain approval for the installation of EV infrastructure, OUC’s financial team must first approve the strategy, and then we formally present it to the board. The strategy behind our presentation is that an investment in EV charging infrastructure promotes the adoption of EVs. The promotion of EVs won’t necessarily show up in OUC’s charging hub, because 80% of charging happens at home or at work, but it will show up in the service territory. So, investing on a break-even or a loss leader basis for Level 2 or 3 charging stations is a good thing, because it removes some of the range anxiety that people have, which is a barrier to adoption. Once you remove that concern, we forecast seeing an influx in vehicles. And I’m happy to share that that forecast has held true.

To provide an example, Orlando is currently number two in the state of Florida, and Florida is number two in the United States, for EV adoption. Back in 2018, there were roughly 2,300 EVs in OUC territory. In January 2022, there were 5,000. This past January there were 10,000, and in April there were 15,000. We’re seeing the S curve. And I’d like to think that a portion of that is because of the programs we’ve put in place to encourage the growth.

If someone only spends $100 with me yearly to charge their vehicle at one of my high-speed chargers, I’m still probably going to see in the neighborhood of an additional $400 or $500 in home charging.

Charged: You are not just providing electricity, you’re also operating charging stations. It seems to me that operating charging stations is a tough way to make a profit—a pretty low-margin business.

Peter Westlake: Well, the high-speed chargers not so much. If we look at a Tesla charging hub that’s operating in our service territory, it drives a fairly significant revenue opportunity. Those are operating in the black very quickly after being installed. We took a charging hub live in July that is one of the largest universal charging hubs. It features 20 CCS DC fast charging stations and it’s located in the heart of downtown Orlando. We believe that it will at least break even, if not better, in the near future. And that’s because, as you get the load up, you start to see more revenue come in.

As a utility, I have the unique opportunity to look at the whole story behind an EV charging hub. If someone only spends $100 with me yearly to charge their vehicle at one of my high-speed chargers, I’m still probably going to see in the neighborhood of an additional $400 or $500 in home charging. So, looking at the whole picture, every EV that OUC helps to put in place represents 1,200 miles of driving. Factor at a rate of 0.33 kWh per mile, and that’s additional energy growth.

Charged: So even if you lose a little bit operating the chargers, you’re winning because that encourages EV adoption overall.

Peter Westlake: Exactly. And no matter who operates the charging stations, we’re the energy source, as long as they’re within our service territory. And honestly, I would love it if charging operators like bp pulse and Tesla come into our service territory and build out the charging hubs, because OUC doesn’t necessarily need to be in the charging business. We need to be in the energy business. But I also know that, if you look back at the history of gas, when automobiles first started out in the early teens, they sold gas at hardware stores and grocery stores and pharmacies and things like that. It wasn’t until Texaco actually started to build gas stations that the fuel ended up in the right spot.

Charged: In California there’s been some backlash to the idea of utilities being charging operators. Some of the independent networks are afraid big utilities will freeze them out of the business. Is that an issue in Florida?

Peter Westlake: I think it’s a perception issue. OUC doesn’t necessarily want to be an operator, so we would happily join hands with somebody who wants to operate, but we need public charging to happen, so in the absence of activity, we take over. Two, three, four years from now, OUC could sell those assets to entities who are interested in solely operating these hubs. And that is not a negative impact to us as a utility, because we’re in the business of selling energy, not charging stations. Right now, with the exception of Tesla, there’s nobody installing enough charging stations to be able to take the load. As a result, OUC is willing to make the investment for the charging infrastructure. But when more people become vested in operating these EV hubs, I am pretty sure OUC would consider handing the reigns over to other entities, from an operational standpoint.

However, I know that there’s going to be areas in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods where it may not be profitable to put in charging stations, but it will be necessary so these communities can have the same access that everyone does. I believe we’ll see the utilities work to solve that problem.

Charged: I see Big Oil moving into the charging space, and having a bit of a suspicious mind, I wonder about their intentions.

Peter Westlake: Well, I think they’ve actually seen the adoption rates for EVs. They’ve seen what’s happening in other countries and what’s happening in the US and they recognize that their market share will fall, and they’ve invested heavily in branches like bp pulse and Shell Recharge and others. I think you’re going to see the gas station model change a little bit and have it serve two masters. And in fact, we’ve had good conversations with bp pulse and with Shell Recharge in our service territory.

Charged: Let’s talk about capacity. The anti-EV crowd is fond of saying that EVs are going to “crash the grid.” Is that a problem? Are you going to run out of generation capacity?

Peter Westlake: From the macro perspective, the analysis is that if every vehicle that’s currently running on gas changes over to electric, you would have to double generation capacity on the grid, and that situation would be problematic.

However, you need to dig into the details and ask: when do they charge? They charge at night. That’s our natural valley when we’re not getting an awful lot of power consumption demand. So it becomes a long time before it starts to tax the grid. Will it be a problem? Most likely there will be situations that we need to address when the tipping point happens. The tipping point is probably at 50%, and we’re still far away from 50% saturation.

They charge at night. That’s our natural valley when we’re not getting an awful lot of power consumption demand. So it becomes a long time before it starts to tax the grid.

80% of charging or more happens at either home or workplace, and if everybody’s charging at home overnight, I don’t see this as being a problem.

We’ve got two EVs in our family. My wife drives a Tesla and I drive a LEAF. We both get our charging at home on Level 1. We didn’t even install a Level 2 charger, because we get enough capacity through Level 1 to replenish what we need for the next day.

Charged: Have you got any vehicle-to-grid projects going on?

Peter Westlake: OUC is starting to think about that. Part of the reticence about getting into vehicle-to-grid was the battery warranties. You start taking the battery and going both ways with it, the manufacturers are a bit leery covering the warranty because you’re using the battery faster than you would naturally. OUC hasn’t gotten involved with it, but there are really only certain use cases, in my opinion, that it makes sense. These are rolling batteries, so they have to be where I need them at the time I need them. Some of the better use cases are things like school buses, where you know where they’re going to be at any one given time.

The other possibility is to mitigate demand. If I’ve got 200 employees that are plugged in at my workplace, I’m going to create demand. And if you create a new peak, then you get into a different rate level. Corporations who sponsor workplace charging are going to want to put in managed charging to make sure that they don’t trigger demand charges.

Those same companies could also say to their employees, “Would you mind if, during the day while you’re plugged in, I use your battery to mitigate my demand level on my building, and I might be able to reduce my energy cost because I’ve done that. I’ll give you free charging if you give me access to your battery when I need it.” Those are models that I think are going to happen.

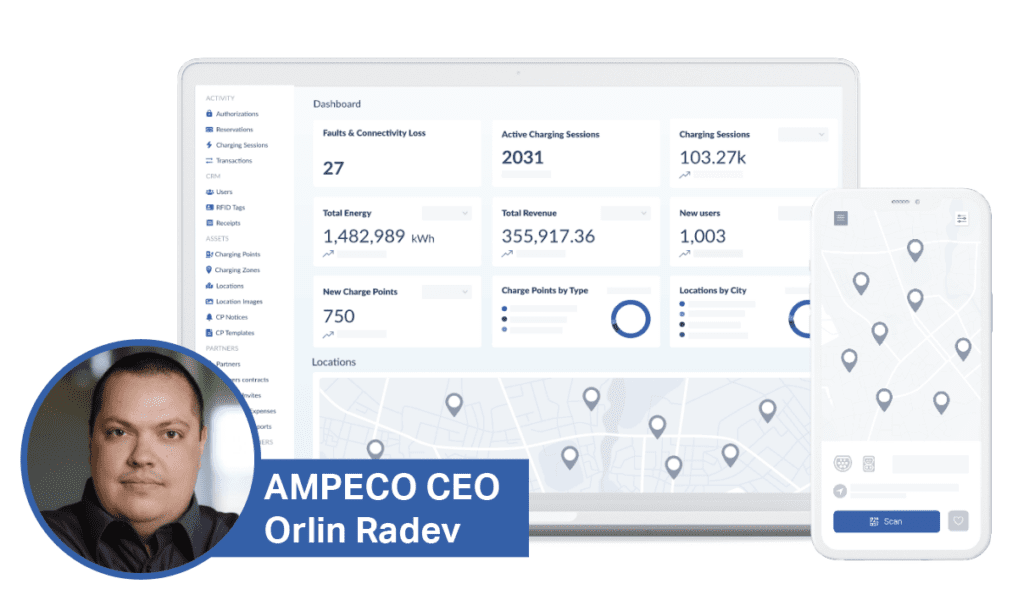

Charged: When you say it matters where the vehicle is, that implies that you need to have some kind of a system to know where these vehicles are plugged in. The CEO of Nuvve, a big player in V2G, told me that in Europe, they’re way ahead of us in terms of information about the grid—more smart metering and that sort of thing.

Peter Westlake: OUC has 100% smart meters in our service territory. We are about to jump into a program where we can determine where people are plugging in EVs, either Level 2 or Level 1. Having that data from our grid will help us understand where EVs are plugging in, so we can better plan our grid and identify areas where we might have concerns.

The electric signature of a charging station is a bit different than a refrigerator or a freezer. You can tease out where a Level 2 or a Level 1 charging station is located by looking at five-minute-interval data. If you plug a car into a charging station, power draw will ramp up quickly and then it will trickle down, whereas a refrigerator will come on and stay on. It’s a signature that people can actually look for. A smart meter gives you the data, but there are software programs that are able to analyze the data and say, “I think a Level 2 is right there.”

Charged: We write a lot about commercial fleet operators, and one topic that’s continually coming up is how getting utility service to a charging depot can be a big bottleneck. Can you give me an overview of the procedure for a charging depot to get hooked up to the grid?

Peter Westlake: A traditional fleet is not a key account for a utility. It’s probably a bunch of trucks that are operating in a gravel lot with a single hut and a light swinging in it and a computer, right? Not much of a power draw. All of a sudden you electrify it, you’ve got a huge customer. So they’re not on our radar right now. We’re not in the business of talking to fleets on a general basis. We talk to Universal Studios, we talk to the airport, we talk to the hospitals, because they’re large customers, and we’re better attuned with what they’re doing. But EV fleets are new things that are happening. At OUC we are taking steps to rectify this by reaching out to local fleet operators.

We’re starting to see the fleets and utilities recognize that we’re two disparate groups that need to work together. As a company, you can’t purchase 100 electric vehicles and then ask your local utility to come set up the charging infrastructure quickly. As a result, OUC is trying to reach out proactively and start to address this need before the fleet is purchased. In fact, we’re trying to organize a commercial ride-and-drive event that would go across the state of Florida in the fall, to reach our fleet customers. We procured a database that tells us who’s investing in fleet vehicles, and we’re trying to engage them in a conversation that says, “Ultimately, you’re going to change your fleet because the TCO (total cost of ownership) is going to force your CFO to make you buy a bunch of EVs. Let’s get ahead of that and start talking about what the true costs are, and let’s talk about the timing. It takes a year to get a transformer. If you’re going to explore installing EVs that will take your power load over what I’ve got allocated for you right now, I’ve got to upgrade your infrastructure. It might take me one to two years to do that, so the sooner I have a conversation with you…”

Now, I can almost guarantee that fleet customers are not going to go all in the first year. They’ve got to get used to a whole new technology, so they might only plug in two or three pilot vehicles to start. And that’s not going to be on our radar because you can do that with an electrician. Ideally, we get them at the pilot stage so we can say, “When that pilot’s successful (and we know it will be), you’re going to order 100 more of these things and you need to be in lockstep with us planning for that so that we can order the transformer, order the upgrades and get them on the list. So when the cars arrive, you’ve got places to plug them in.”

There are currently over 100,000 commercial vehicles in the city of Orlando, and an estimated 1,000 fleets reporting as active in our service territory. If they all decided to suddenly adopt EVs for their fleets, OUC would be extremely challenged with implementing the necessary infrastructure to support that new adoption rate. As a result, we really want to get ahead of that possibility.

We just joined the Trucking Maintenance Council, which is a fleet organization, and we attended their conference here in Orlando. We were one of only two utilities that attended. That’s a national conference, and only two utilities showed up. So these are two groups that need to get together, and they need to start doing it now.

Charged: What about a specific example? Let’s say I call you up and I say, “I got a fleet. We’re going electric, and I need seven megawatts of power.” What steps are we going to have to go through and how long will that take?

Peter Westlake: Well, the answer depends on additional information I would need. What kind of power is already served at the location? Do I have seven megawatts of power capability? I might not have a transformer big enough to be able to dispatch that. At a minimum, if I’m going to upgrade the transformer, it’s probably a year to do that sort of work. If I’ve got to bring power, like a new duct bank or a new primary power source to the location, that could extend the project into two years. If I need to install a new substation, then now we’re talking years. For example, we’ve been in conversations with LYNX, our mass transit agency here in Orlando, for two or three years. We know that they’re planning to add 150 vehicles in the near future, and we know we need to be planning for that. The lead time can be huge in our business, which is why we need to know what your plans are during the pilot stage, not during the transition phase.

Charged: Can you give me any examples of EV fleets that you’re serving right now?

Peter Westlake: LYNX is a big one. Their downtown core of buses is electrified. They’ve won some federal Low-No grants that’ll bring them up to 40 or 50 e-buses. They’re planning to be 50% electric, 50% CNG by 2027. That’s one large fleet that we’re working with. We’re also working with Amazon—they’re looking at hubs for charging in our service territory.

This article appeared in Issue 65: July-September 2023 – Subscribe now.