- The electric road ahead for heavy trucks is not exactly clear, and there are several roadblocks, some obvious and some far less so.

- Fleets don’t want to go electric at scale until they’ve done years-long pilots, but the Advanced Clean Trucks regulation will artificially constrict that timeframe. Soon they won’t have a choice.

Q&A with electric truck expert Rustam Kocher

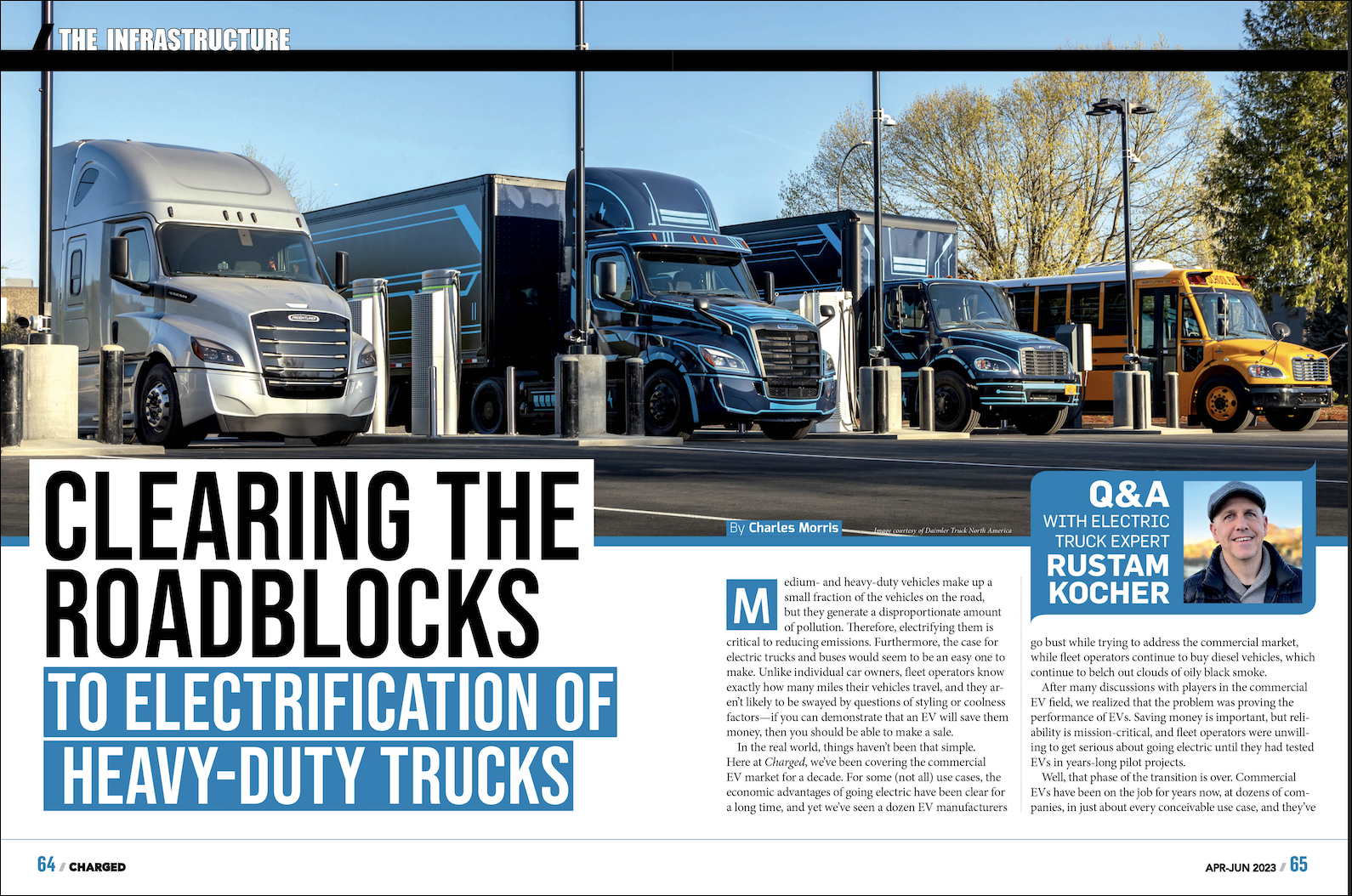

Medium- and heavy-duty vehicles make up a small fraction of the vehicles on the road, but they generate a disproportionate amount of pollution. Therefore, electrifying them is critical to reducing emissions. Furthermore, the case for electric trucks and buses would seem to be an easy one to make. Unlike individual car owners, fleet operators know exactly how many miles their vehicles travel, and they aren’t likely to be swayed by questions of styling or coolness factors—if you can demonstrate that an EV will save them money, then you should be able to make a sale.

In the real world, things haven’t been that simple. Here at Charged, we’ve been covering the commercial EV market for a decade. For some (not all) use cases, the economic advantages of going electric have been clear for a long time, and yet we’ve seen a dozen EV manufacturers go bust while trying to address the commercial market, while fleet operators continue to buy diesel vehicles, which continue to belch out clouds of oily black smoke.

After many discussions with players in the commercial EV field, we realized that the problem was proving the performance of EVs. Saving money is important, but reliability is mission-critical, and fleet operators were unwilling to get serious about going electric until they had tested EVs in years-long pilot projects.

Well, that phase of the transition is over. Commercial EVs have been on the job for years now, at dozens of companies, in just about every conceivable use case, and they’ve proven that they can do the job better, quieter, more safely and above all, cheaper. Upfront costs are steadily approaching parity with legacy vehicles, purchase incentives are available, and new programs at the levels of federal (IRA, BIL), state (California’s ACT and ACF) and local (city zero-emission zones) government are driving (some would say “coercing”) companies to move forward quickly.

However, the electric road ahead is not exactly clear. There are several roadblocks on the way to an electrified trucking system, some of them obvious and some far less so.

Rustam Kocher has been a pioneer in the commercial EV field. When Charged first spoke with him in 2021, he was the Charging Infrastructure Lead at Daimler Trucks North America, and also the Chair of CharIN’s Megawatt Charging System (MCS) task force. He later served as Transportation Electrification Manager at Portland General Electric, so he’s worked both sides of the electric fence. Now nominally retired and living in Portugal, he remains active in the infrastructure space as a consultant, and closely follows the development of the EV charging ecosystem. If you want to stay up on developments in the commercial EV space, you could do worse than to follow Rustam’s LinkedIn feed.

Charged: You recently wrote, “Commercial vehicle battery packs are tough to source.” Lots of fleets will be placing orders for heavy-duty EVs over the next few years. Is the supply of battery packs going to be a bottleneck?

Rustam Kocher: I think it’s going to be an issue for any company that has a large battery pack. Tesla, for instance: if you look at their battery pack in the Semi, it’s roughly 800 kWh, and you’ve got 74 kWh on a Model 3, which means you could make roughly ten Model 3 battery packs with the same number of cells as you’d need for one Semi. So, Tesla can make more margin selling ten Model 3s than they can on one Semi.

You could make roughly ten Model 3 battery packs with the same number of cells as you’d need for one Semi.

Every company is going to be faced with that issue, whether or not they make light-duty and medium- and heavy-duty EVs, because the battery manufacturers are also going to look at quantity and volume, and if they can sell at a higher volume to light-duty and consumer vehicles, then they’ll be less interested in providing packs for larger EVs.

It’s easier to sell to the light-duty market. It’s less time and effort. If you’re CATL, you can sell in mass quantities to GM and Ford. Supplying to Volvo Trucks or Daimler Trucks or whoever is more burdensome.

Also, the demands for medium- and heavy-duty battery packs are much more complex. In a commercial vehicle, you have a lot more forces in play, such as G-forces on a truck, that you have to test for. For commercial vehicles, the cells have to be able to perform at a different level.

For example, the kingpin that the truck smacks onto when the driver backs up to pick up a trailer, the G-force in that transaction is significant. But that’s also where the battery pack sits, so that battery pack has to be mounted in such a way that when that truck backs up and hits the kingpin and grabs the trailer, it doesn’t jar it and cause shorting issues or whatever else over the long-term life of the battery.

Everything on a commercial vehicle has to be more rugged. Most commercial trucks are engineered for 1.2 million miles.

Everything on a commercial vehicle has to be more rugged. Most commercial trucks are engineered for 1.2 million miles, so the engineering that goes into making those vehicles be able to perform and last that long has to apply to the battery pack as well. So, it’s a technical challenge and it’s a lot of cells.

When we were first starting off at Daimler Truck, trying to find a battery cell supplier that would build us a pack that was good in the truck was difficult. Your supplier pool is restricted to who can make what you want and who wants to make what you want, so you have to deal with a smaller number of suppliers. The more suppliers you have, the more competition you have, which means the pricing and performance from those suppliers are going to be better. If you’ve got a limited supplier pool, they’re going to be less inclined to give you a good price for good performance.

Charged: You’ve also said that heavy-duty charging is going to be a huge hurdle.

Rustam Kocher: It is. I was a big part of building the first-of-its-kind—at least in the Western world that we knew of—heavy-duty charging site in Portland, Oregon. It’s called Electric Island.

You’re not going to be able to pull a Class 8 truck up to a consumer charging station and charge it towing the trailer. It won’t work. We’re going to need purpose-built sites, and we [decided to] build one so we could show people what it would look like.

Electric Island did what we hoped it would do, which was to kick off a movement towards knowing what was possible and what needed to be done. If you don’t build something like that, people can’t refer to it. What Tesla did with their Supercharger network was really difficult because no one else had ever done anything like that. They thought through all those problems: Where should the charge port be? How long should the cable be? How should the vehicle interact with the charger? All those things. And they came up with a pretty bulletproof solution.

What we wanted to do with Electric Island was play with all those things. In fact, the code name for it internally was “the sandbox,” because we wanted to be able to build up a sandcastle and learn from that process and knock it down and build another one. The site was built with maximum flexibility so that we could change things, swap out chargers, move things around and learn from the process of installing battery electric storage or putting solar on the site or what a megawatt charging unit would do under full power in partnership with the utility. What happens when we plug in 1.2-megawatt chargers? Will the lights all dim?

Portland General Electric was also involved with the West Coast Clean Transit Corridor (WCCC), which is a movement towards getting truck and bus charging stations like Electric Island built from Vancouver down to San Diego so that you could move goods and freight all up and down the West coast, at 50-mile intervals. [This project is currently at the stage of conducting grid readiness assessments.]

What we did, again, was try and show what’s possible, and what needed to be done in order to enable goods movement and usage of battery-electric trucks. So we set out to show the industry what needed to be done so that the Flying Js, the Chevrons, the BPs of the world would understand that this needs to be built and that they had some support in doing so.

The utilities did all the desk reviews, they evaluated each of the sites generally and said, “Okay, it’s going to be this much on upgrades and this much time. We built it out in historical growth segments so that people would know if they’re going to build a site there, how long it would take and what it would take to get a site to 3.2 or 12 MW.

Charged: A couple of companies are building big commercial charging hubs—WattEV (I know you serve on their advisory board) and Terawatt. What’s different about their business model?

Rustam Kocher: There’s also a couple more out there building charging hubs for trucks. There’s the partnership between Daimler and BlackRock, called Greenlane, and Forum Mobility, which is building a charging network for drayage trucks.

We need a dozen companies that are willing to do this. We need Love’s, we need Flying J, we need Pilot, we need all of them.

WattEV saw the need and they moved prior to the market growth. Power to them for seeing it, understanding it, and being willing to be a first mover. Terawatt as well. I’m excited for both of them to be successful—we need more. We need a dozen companies that are willing to do this. We need Love’s, we need Flying J, we need Pilot, we need all of the current fleet fuel and service providers to move to providing electricity for medium and heavy trucks and buses. If we’re going to hit the numbers we need to hit for fleet adoption, we need as many places for those vehicles to recharge as possible.

WattEV’s first site is in Bakersfield. They’re building a massive site with onsite generation, solar+storage, which is important within the Megawatt Charging System. Megawatt charging is going to have really high demand charges [fees that utilities charge if peak demand exceeds a certain level] unless you have some way to mitigate those peaks. And having stationary storage on site will be important for that. They’ve also got a site at the Port of Long Beach and a couple others in the LA area. Those will be public-facing truck-charging sites similar to Electric Island.

But then they did something interesting. They said, “We’re going to build new sites and there’s simply not enough trucks on the road today for us to get the volume we need for the site to be profitable.” And they recognize that there’s a lot of small fleets that serve drayage in and of the ports of Long Beach and LA that are served by owner-operator fleets that only have a few trucks. Those guys don’t have the wherewithal to finance a battery-electric truck that costs twice as much as a diesel truck, and they’re usually buying third- or fourth-owner diesels anyway, that are super-cheap. So WattEV is going to offer truck-as-a-service. They will own, maintain and insure the trucks, and then the owner-operators can rent them on a daily, weekly or monthly basis. WattEV will also provide the charging for those trucks, so it’s a way to allow some of these smaller fleets that serve freight in and out the ports to be able to comply with the California regulations so they can stay in business and keep operating cleanly. And it generates flow through the WattEV site so that they get a consistent number of trucks coming through. Because the flatter your demand curve is, the lower your power costs are from the utility. If you have a really peaky and spiky demand, your power costs can be really high because utilities don’t like that, and they charge accordingly. They want a nice solid demand line, so if you can keep a site active as much as possible, then you’ll have lower overall power costs.

Charged: Tell us more about issues with the utilities and how that can be a bottleneck.

Rustam Kocher: Public utilities are there to serve the public—whether they’re investor-owned, co-ops, city-owned, whatever, they’re there to serve the ratepayer. When your home was built or when the business next to you was built, they went to the utility and said, “I need a hookup to the grid.” They didn’t have to pay extra for that hookup if it wasn’t exceptional—if it wasn’t very far to where they needed to get hooked up, that cost was essentially free.

It was free to the builder, but it wasn’t free to the utility. What they do is they rate-base that work. In order to get half a megawatt to the supermarket down the street, they had to trench, they had to make the connection, they had to make sure they had enough generation, they had to serve that site. That cost is spread among all ratepayers for that utility. That’s an accepted practice for utilities because that’s what a utility has done over the last hundred years.

What hasn’t normally been done is transportation electrification work—what’s on the utility side of the EV. So if I’m Tesla or Electrify America, or a truck fleet that wants to have an electrified depot, and I go to Southern California Edison, and I say, “I need an interconnection to grid for this transportation electrification site,” there’s no stipulation that says that that work should be offset by the ratepayer, so that cost is typically born by whoever’s building the site, which gets expensive. If Tesla needs to come in and build a charging site, they’ve got to pay for the grid connection.

California has passed Assembly Bill 841, [signed into law in 2020] which says that transportation electrification must be treated just the same as building construction. So now that utility-side work can be done in a rate-based manner, which means that the individual site builder doesn’t have to pay for that work out of their own pocket, which is what needs to happen everywhere.

The way that you can spread that cost to the ratepayer for transportation electrification sites is important, and it needs to be done with every publicly-owned utility across the nation. The problem is those laws are all state-based and every state has to make that change at the level of the utility commission.

Charged: It’s not just the cost—time can also be a big factor. As someone pointed out to me, if you’re building a factory and it takes two years to get your utility connection, that’s okay, because the factory’s going to take two years to build anyway, but a charging site can be built much more quickly.

Rustam Kocher: I told this story over and over to the utilities every chance I got. It’s like gravity has changed for the utility industry. From the time of the first utilities until today, everything took a certain amount of time. If they needed to make an interconnection because a building was going to be built, they had 18 to 24 months, because you don’t build a building faster than that. Gravity always worked in a certain way—you always had this much time to do whatever needed to be done. Today, Sysco could order trucks from Tesla or Daimler and get electric trucks in a month or two, and they can be connecting temporary charging solutions to their warehouse when the trucks arrive. Utilities don’t respond to grid upgrades and interconnection upgrades in two months. They just don’t operate that quickly. They never have, they’ve never needed to. Well, suddenly gravity is heavier. A lot heavier.

The trucking industry is very, very old-school, very, very conservative. You’ll see pushback from them until TCO becomes positive operating the vehicles.

Charged: I’ve been seeing articles from trucking industry groups that say things like, “Don’t get us wrong, we love EVs, but it needs to be a nice smooth, gradual transition,” by which they mean that there needs to be minimal government regulation. An official from the American Trucking Associations (ATA) recently made a speech in front of the US Congress, which contained a number of incorrect statements about EVs. Are we going to see a lot of resistance to electrification from the trucking industry?

Rustam Kocher: Yes. Any change is hard. And this industry is very, very old-school, very, very conservative. You’ll see pushback from them until TCO becomes positive operating the vehicles. Once your total cost of ownership is lower with a zero-emission vehicle, then that’s a spreadsheet decision. Then I can plug that into a business plan and say, “I can offer lower freight rates than Joe down the road, who’s operating diesel trucks, because his cost per mile is more expensive.” Once that happens, then your adoption curve skyrockets. It turns into a hockey stick, which we’re already seeing with passenger cars. And the commercial vehicle hockey stick will be more pronounced, because it is a spreadsheet decision. Nobody buys a commercial truck because it looks good. They buy to make money.

[Editor’s note: A group of the nation’s largest truck-makers have now pledged to comply with California’s Advanced Clean Fleets (ACF) rule.]

Charged: When do you see the TCO clearly becoming better?

Rustam Kocher: My guess for commercial trucks is the early 2030s, but there’s going to be some binary decisions that fleets are going to have to make before then. For instance, in states that have adopted the Advanced Clean Trucks regulation [15 US states at last count], you have to hit certain emissions benchmarks. You’re either operating by hitting those benchmarks with ZEVs or you’re not, so your choice is operate or not operate. And yes, you may have slightly higher costs because you’re forced to operate ZEV trucks as per regulation. And then in Europe, some of the major city centers have created zero-emission zones, so if you want to deliver to Starbucks within Paris, you’d better have an electric truck.

Charged: Early 2030s? Is it really going to take that long?

Rustam Kocher: It depends on a couple of things. I’m watching battery prices, I’m watching component prices, I’m watching the tick-tock of new models coming to market, from gen one to gen two, to gen three to gen four. I call that a “tick-tock,” like what Intel does with the speed of their chips. So, how quickly the OEMs go through their iterations and learn and equip new products, new battery packs, new chemistries, those sorts of things.

You’re already seeing different (LFP) batteries on the Tesla Semi, which is interesting. So now they think maybe they don’t need a 500-mile range, maybe they can get by with 300. Well, that helps the OEMs out there that can just barely reach 300. There’s a lot of use cases for 300-mile trucks out there, so let’s do that with LFP batteries. Iron phosphate batteries are great because they’re durable, they’re cheap. They’re a little heavy and they’re not quite as energy-dense as some of the other chemistries, but they’re a good fit for commercial use because of their durability.

As the industry is able to go through these iterations and get some serious production trucks out there, learning from failure and iterating will make the products better. All these OEMs have had a really slow iteration cycle in the past. Typically, from model to model, it was about eight years, which is just fantastically slow in today’s BEV world. Now they’re down to roughly two, and I think they’re probably going to have to get down to about a year.

It’s going to be a big lift for the industry. They won’t like it because they want to validate everything. They never want to put something out on the road that hasn’t been fully validated, but in some cases, they’re going to have to do virtual simulation instead of on-road validation.

Charged: There’s another bottleneck. Fleets don’t want to go electric at scale until they’ve done pilots for two or three years. Do you think that timeframe is going to get condensed?

Rustam Kocher: It will be artificially constricted by the ACT. They won’t have any choice. And so they’ll choose OEMs that they trust and move forward. Whether that’s Volvo, Freightliner, PACCAR or Navistar, they have relationships with those OEMs and so they’re going to trust them to build a vehicle that will perform under the conditions that they need it to perform. Tesla’s going to have trouble breaking into the market. Nikola I wouldn’t expect to be around much longer, but other companies like Motiv and Proterra hopefully will have carved out enough of a niche to stand on their own two feet.

Charged: These articles about “sensible regulations” and “smooth transitions” tend to say a lot about hydrogen, CNG and e-fuels. Is there a real danger that the industry will go down one of those dead-end roads?

Rustam Kocher: There is. I am quite worried about hydrogen sucking some of the oxygen and funds out of the room. To me, hydrogen is a way that the oil and gas industry can stay relevant. What are they good at? They’re good at pumping things out of the ground, storing it, refining it, piping it or trucking it to a place, compressing it or putting into the tank and then dispensing it. Hydrogen fits all those things really well. But it doesn’t work. It’s not efficient. It’s extremely expensive. It’s technologically almost impossible to do it safely.

Big Oil’s got a lot of resources and money to push this narrative and you see it all day, all the time. When we look at the federal funding for charging and whatnot, they always have hydrogen in there at a similar amount of money as BEV. There’s no need for it. There are almost no hydrogen vehicles out there because they cost so much more per mile to run.

MCS should put a bullet in hydrogen because the only thing that they have going for them is speed of refueling.

That’s why I love the global effort to standardize the Megawatt Charging System, and hopefully Tesla will come on board with the rest of the industry. MCS should put a bullet in hydrogen because the only thing that they have going for them is speed of refueling. With MCS it’s the same speed. In fact, it might be faster, so hydrogen can go pound salt.

Batteries are only going one way. Gravimetric density is improving, volumetric density is improving, charging speed is improving, and all those curves are heading the right way. None of them are slowing down, so we know that batteries are on an improvement curve that will continue. Solid-state batteries can charge almost instantly. StoreDot has those organic-chemistry batteries, which can charge super-quick. So if you can get your Megawatt Charging System and a big StoreDot battery, we can charge it in maybe 12 minutes, 15 minutes.

Charged: It has long seemed to me that within every automaker there are pro-EV and anti-EV factions eternally contending for the mastery. Is that the case with the commercial vehicle makers too?

Rustam Kocher: Even more so. When I started at Daimler Trucks, a member of the board came by to visit Portland from Germany. As the new hire, I got to ask them a question—this was 2012. I said, “What is the plan for the decline of the diesel engine and the switch over to new technology, whether it’s hydrogen or batteries?” And he literally laughed and said, “Diesel is the drivetrain for the foreseeable future, period, end of statement.”

And I made it my focus for the rest of my time to agitate for electrification because I felt that they were missing the boat. I started a newsletter internally about electrification in the industry, and I sent it to the CEO and the board. And then I got the opportunity to join the e-mobility group and the rest is history.

Charged: So you were one of the pro-EV partisans, agitators…

Rustam Kocher: …lobbing Molotov cocktails over the wall.

Charged: Which of the big OEMs are the ones to bet on to lead in the electric brave new world?

Rustam Kocher: I’ve really been impressed with Volvo Trucks. What they’ve done in electrification, both in the European market and the US market, has been tremendous. There’s still internal factions there, but they seem to be moving very quickly in the right direction. The eCascadia by Freightliner [a US subsidiary of Daimler] is a fantastic product, I’m excited to see more of those get produced out of the factory in Portland and get on the road. The Traton Group [a subsidiary of Volkswagen], is doing great work primarily in Europe, as is Daimler Truck Germany. They’re more regulation-forced because they’ve got some pretty strict deadlines that are coming up for truck electrification within the European Union. They’re really under the gun, so most of the major truck manufacturers are pushing hard to meet those regulations, because otherwise the fines are really, really expensive—in the billions of dollars.

Tesla is on gen five because they built that truck from the ground up to be electric, which none of the major OEMs have yet.

Tesla, obviously, they’ve got a great product. We talk about gen two, gen three with the OEMs right now and maybe PACCAR and Navistar are on gen one, gen two. Tesla is on gen five because they built that truck from the ground up to be electric, which none of the major OEMs have yet. They’ll get there, but honestly Tesla is that many more jumps ahead. Whether or not they can keep their truck intact, maintain it and build the trust within the industry is a good question—we’ll see. I hope they can. I’ve never worked with smarter people. I’ve never worked with a more agile company than when I was working with Tesla on the Megawatt Charging System.

This article appeared in Issue 64: April-Jun 2023 – Subscribe now.