A recent survey of new-car buyers suggests 4 of 5 will be able to charge an EV at home—making it even more critical that they understand how charging is actually done.

If projections from major carmakers are to be believed, the bulk of electric cars that will travel on US roads in 2026 haven’t been sold yet. Over the next five years, EV sales are expected to rise steadily, surpassing in five years the 1.4 million sold in the previous 10 years.

The industry and the journalists who cover it often focus on the 17 million new vehicles sold each year in the US, not the roughly 40 million sold as used cars. But as EV percentages grow, those new vehicles will contribute the bulk of the demand for EV charging by 2026—not the used ones.

To understand how and where those new EVs will be charged, we need to look at the people who will buy them—and not the much larger pool of US drivers overall.

To understand how and where those new EVs will be charged, we need to look at the people who will buy them—and not the much larger pool of US drivers overall.

Buyers of any new vehicle occupy the upper end of the economic scale. With the economic impact of the Covid pandemic unequally distributed—those at the bottom end of the economy were affected far more than the professionals who found they could work from home—that trend has only increased.

And those buyers are now willing to pay more for their vehicles. With income from working during lockdown that they couldn’t spend on vacations or meals out, plus limited supply of new vehicles due to chip shortages, fully 40 percent of new-vehicle shoppers would pay up to $5,000 over sticker price to get the vehicle they want, according to a Cox Automotive study last month.

The result is that new cars have gotten steadily more expensive, and at a faster rate. The average transaction price of a brand-new vehicle sold in April was $40,768, according to Kelley Blue Book.

As the industry tries to predict the charging behavior of all those new EV drivers, data from a 2013 study published by Carnegie Mellon is sometimes used to suggest overnight home charging is only suitable for a small number of Americans.

While it’s certainly not suitable for all EV buyers, a new survey suggests at-home charging will be a much larger part of the total than suggested by the CMU study. And that understanding makes it even more crucial to address the lack of awareness of home charging among potential EV buyers identified in the J.D. Power 2021 EV Home Charging Study.

(Those buyers will separately still have to be educated on the different types of EV charging, how each works, and where they’re found—but that’s a topic for another time.)

SEE ALSO: Shoppers buy more EVs if they understand charging—and now there’s proof (exclusive first look)

The conventional wisdom is wrong

Those who study and project EV charging behaviors may look to the CMU study published in 2013, US residential charging potential for electric vehicles. In particular, the following data from the summary are often quoted as conventional wisdom (our boldface):

“While approximately 79 percent [of] households have off-street parking for at least some of their vehicles, only an estimated 56 percent of vehicles have a dedicated off-street parking space – and only 47 percent at an owned residence.

“Approximately 22 percent [of] vehicles currently have access to a dedicated home parking space within reach of an outlet sufficient to recharge a small plug-in vehicle battery pack overnight.”

The calculation that 78 percent of US vehicles are unable to charge at home is often cited verbatim. It does not take into account that adding a new outlet or charging station to a garage can be a simple modification, though it isn’t always. (My garage fell into that 78 percent until I added a circuit for a Level 2 charging station—at roughly the same cost as adding an electric clothes dryer and its circuit.)

The number of plausible dedicated home-parking spaces throughout the US where charging is practical is likely somewhere between the pessimistic 22 percent and the 79 percent number for “off-street parking for at least some of their vehicles.”

But a glaring nuance has been entirely lost in using data from the CMU study. That paper covers all households in the US—not the smaller subset of households lived in by the people who actually buy new vehicles.

But a glaring nuance has been entirely lost…That paper covers all households in the US—not the smaller subset of households lived in by the people who actually buy new vehicles.

Americans who can afford new cars can charge at home

Looking at new data that surveys only those who can afford new vehicles today, it turns out that four of five of those households have dedicated off-street parking—right at the high end of the CMU number for “off-street parking for at least some of their vehicles.”

That percentage is likely a proxy for household income: the higher your income, the more likely you are to live in a single-family home with its own driveway. The data is from the Escalent EVForward 2021 study, which surveyed 10,000 respondents chosen to reflect all types of current new-vehicle buyers.

They included a small number of existing EV owners—2 percent or less, given the current low sales rate—and some EV-curious + EV intenders, but also EV haters, the utterly disinterested, and everyone in between. No new-vehicle buyers were excluded.

Of that survey group, 84 percent said they owned their own home. 55 percent said they would be able to charge in their garage, and another 33 percent in their driveway. Those percentages are slightly higher than they were in the 2020 survey, which may indicate increasing affluence among new-vehicle buyers, as average transaction prices continue to climb.

Large numbers of those households will likely have to add a 120-volt outlet or 240-volt Level 2 charging station in or on their garages. But buyers who pay an average of $40,000 for a new vehicle will be far more capable of covering that cost than those living in rented apartments or townhouses.

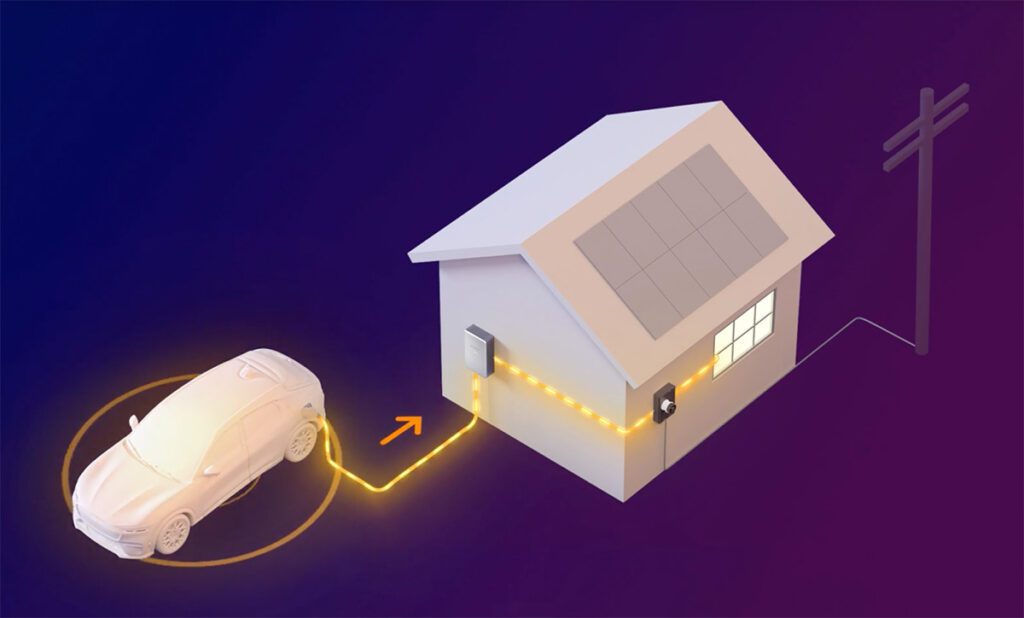

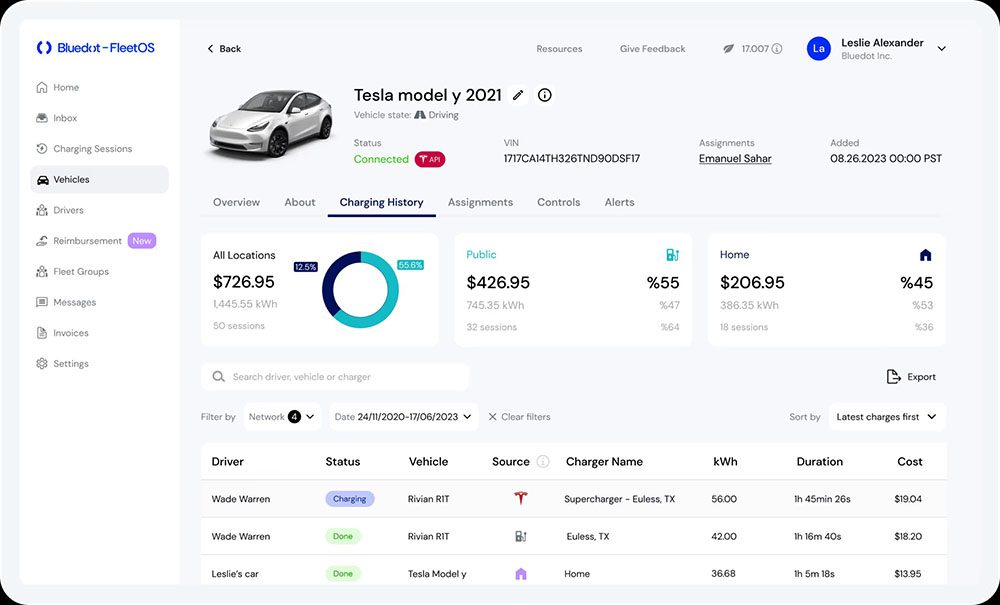

And with today’s longer-range EVs, the need for a “full charge” every night is reduced. Christian Ruoff, publisher of Charged, notes his family has charged its Tesla Model Y in the driveway via a 120-volt plug for more than a year now. They’ll upgrade “eventually,” he says, but it just doesn’t seem necessary when they average only 30 or 40 miles a day.

Once in a while, he noted, he charges the car more fully at a nearby DC fast-charging site. Otherwise, that 120-volt socket works fine—adding 40 miles over 10 hours each night—for a long-range EV used only 250 miles a week. And that may be how many new EV drivers start.

Older houses or those built under more lax local building codes may not yet have 200-amp service from the curb, which allows an EV to charge at 240 volts while the rest of the house is operating at full demand. That requires more effort and cost. But newer suburbs won’t have any problem.

Street-parkers, apartment-dwellers, and used-EV buyers have it rougher

This is not in any way to ignore the very real challenges of charging an electric car for drivers who lack dedicated off-street parking. They include those living in apartment buildings, townhouses with grouped parking areas, and older city neighborhoods with curbside parking.

Over time, used EVs will come into their own as affordable transport with low running costs, if buyers can charge conveniently. This generates significant questions of equity and fairness, which require policies that specifically site public-charging infrastructure in disadvantaged or dense urban neighborhoods for residents who drive but cannot charge at home.

Still, the millions of buyers who will add new EVs to the US fleet over the next five or 10 years represent the low-hanging fruit for electric utilities—which love the idea of selling more kilowatt-hours overnight, during their lowest-demand hours, for very low additional capital investment.

But new-car shoppers, per the J.D. Power study, still don’t know they’ll charge the bulk of their EV miles at home.

But new-car shoppers, per the J.D. Power study, still don’t know they’ll charge the bulk of their EV miles at home. That makes it doubly important that automakers create effective, pervasive, targeted programs to explain at-home charging and make it easily and seamlessly available.

If that doesn’t happen, all the fast charging in the world won’t make a difference, because those potential EV buyers will view charging an EV as akin to buying gasoline, only at “a charging station” somewhere else—and they may think they have to do it every day or two, and it’ll take a lot longer than filling the tank.

In other words, overnight home charging will be a big deal—and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Sources: Escalent EVForward