The San Francisco Bay Area is widely considered ripe with potential for early and widespread adoption of EVs. Area residents are generally progressive, environmentally concerned, and technologically literate. The area was an epicenter of electric vehicle deployment during California’s earlier EV Mandate era, and nearly 50 years ago the Electric Auto Association was founded by Bay Area residents. Recently the charging point locator company PlugShare listed the Bay Area at #4 in its list of top 10 electric-car-ready cities. The area is also home to several companies in the electric vehicle space, not only vehicle makers like Tesla Motors and Zero Motorcycles, but component and charging companies like Mission Motors, PolyPlus, Envia Systems, ChargePoint, ECOtality, Clipper Creek, and more.

So, it shouldn’t be surprising that the Bay Area has seen a large influx of electric cars over the last two years. But what may be surprising is a hurdle many San Francisco residents face in successful electric car ownership.

Like most urban centers, San Francisco has a relatively high 67 percent of residents living in “multi-unit dwellings” (MUDs) – apartments, condominiums, etc. A much higher portion than the surrounding counties. Those who live in MUDs face great difficulties getting at-home access to charging stations, aka electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE).

The phrase “garage orphan” describes a similar situation, in which a resident has no off-street parking at his or her residence, or has off-street parking, but no access to electricity.

A key factor in electric vehicle success is the ability to charge at home, which is far more convenient than public charging. Anything which prevents the convenience of having an EVSE at home could impede EV adoption.

The real challenge: HOAs and other covenants

An electric vehicle owner living in a single family residence has a relatively easy time installing an EVSE. It can be as simple as hiring an electrical contractor to install it. In some cases it might require permits, inspections, or an upgrade to the utility line or service panel. This is a walk in the park compared to the task of installing EVSEs in a MUD.

A MUD resident faces a maze of property managers, homeowner associations, rules over use of common space, questions surrounding payment for electricity use, charger allocation among residents, and more. These factors can be absolute roadblocks, or can cost thousands of dollars to rectify.

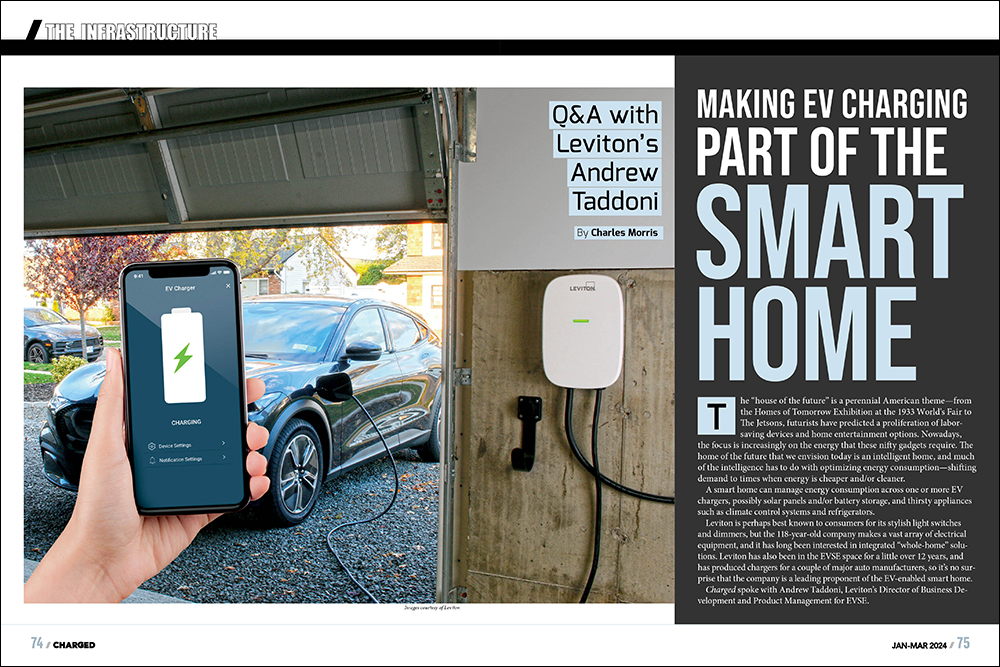

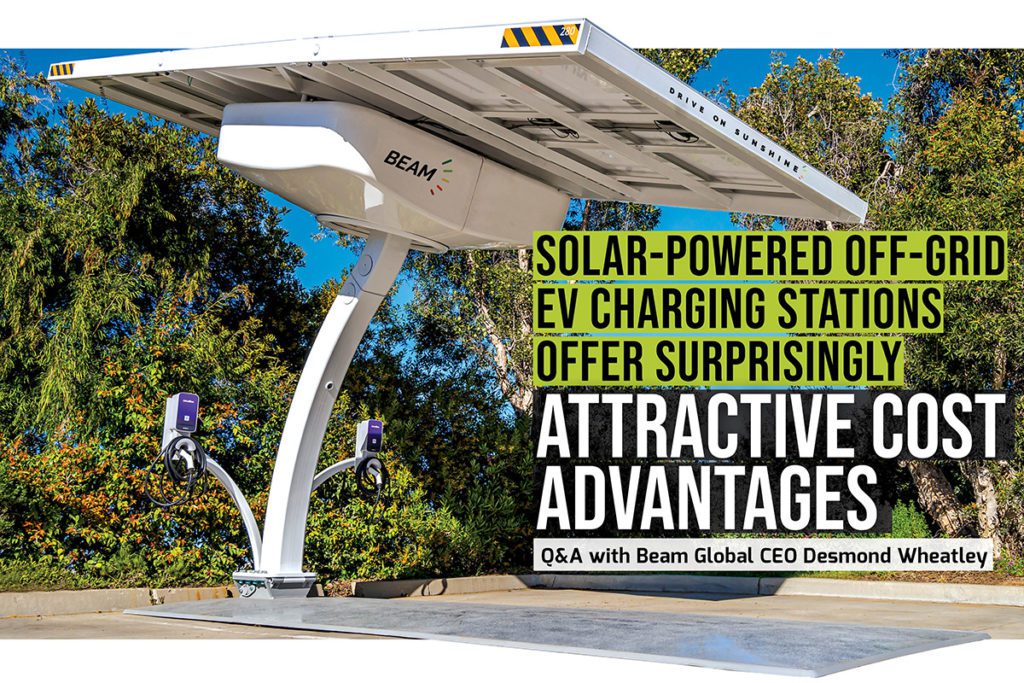

Photo courtesy of ChargePoint

A report by the UCLA Luskin Center for Information offers a list of major challenges (we found similar issues in reports written in Maryland and Seattle, and by staffers with the San Francisco Department of the Environment):

Approval for installation by building management, landlord, or home owners association. The specific situation is different for each building, but clearly the owner has a strong vote in what happens to their building. Residents may fear repercussions if they press too hard. Building management may be put off by the complexity of installing an EVSE. At the same time, an electric car-owning MUD resident has a pressing need to recharge their car while it is parked at their home.

Determining who is responsible for EVSE installation costs. The installation can be expensive. Each building is governed in its own way, with a variety of legal arrangements around the allocation of parking spaces and allocation of costs for common areas. Will the EVSE be seen as an extra benefit for one person? Will the landlord be reluctant to take ownership of the EVSE? If the resident pays for the EVSE, will they forfeit their investment when they move? If the EVSE is installed for common use, who will enforce a sharing protocol?

Determining payment system for electricity usage. If the station uses common “house power,” how can payment for that electricity be allocated to the electric car owner? The EVSE could be attached to a resident’s individual meter, but that could raise too much installation complexity.

Insurance coverage for the EVSE. California laws S.B.209 and S.B.880 prevents home owners’ associations from dismissing EVSE installation, as long as the residents meet a list of requirements, one of which is $1 million of umbrella liability insurance.

Distance from assigned parking to electrical service panel. In some cases residents have assigned parking spaces, and some of those cases will require an expensively long conduit run.

Electrical capacity. Adding one or more EVSEs could push electrical demand to the point of requiring an upgrade to a building’s electrical service. It might not be the first EVSE, but the 4th or the 10th EVSE. Who will be responsible for paying for that upgrade? The unlucky EV owner whose EVSE triggers the need for the upgrade? Or should the cost of the upgrade be carried by the building owner? Or should it be shared by the other EV owners?

WiFi may not be available in underground parking. Some EVSEs use WiFi or cellular system data communications to send data to central computers, and the required signals may not make it to the EVSEs.

EVSE subsidies available only to the EV driver. The government subsidies available to defray EVSE costs are only given to drivers, not building owners.

We’re the government, we’re here to help

Residents of MUDs are faced with contracts governing their residence. In the eyes of the law, this is primarily a matter of contracts between an individual and a property manager. What, then, is the role of government in this issue? Many have made a case that widespread EV adoption serves the common good, and that government’s primary role in society is to enact policies that support that common good. In this situation, some local, state, and federal policy-makers are taking action to rewrite the laws as necessary.

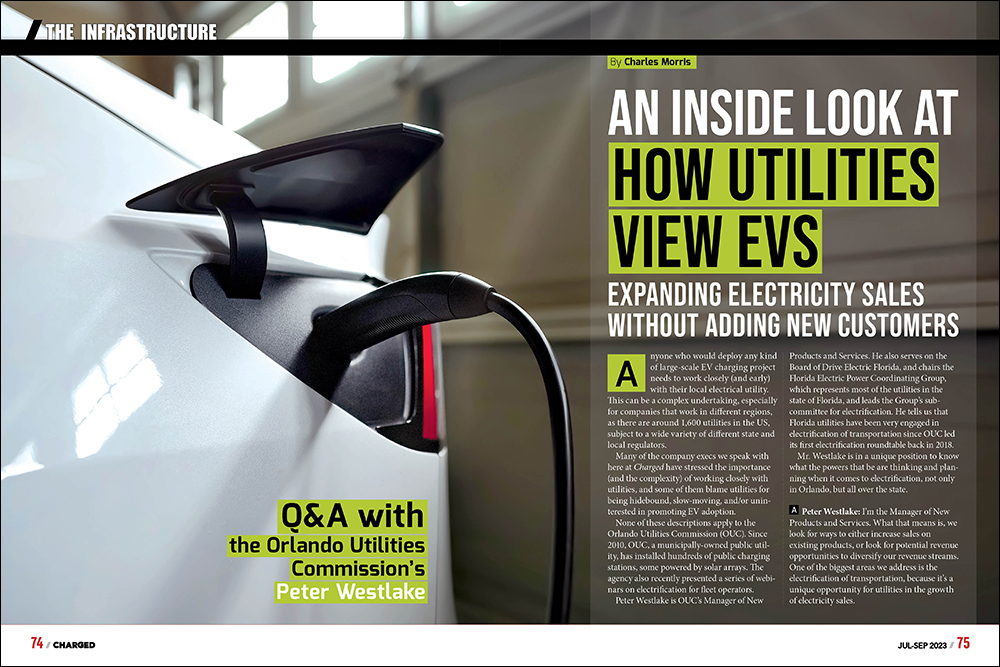

Photo by Alex E. Proimos

The California legislature passed two laws, S.B.209 and S.B.880, that together seek to address whether a property owner can take a hard-line position of preventing EVSEs. Essentially these laws restrict a property owner from outright dismissal of a resident’s request to install a charger, if a list of requirements have been met. Some of the terms include:

- That $1 million liability insurance policy we mentioned, to be carried by the EVSE owner, with the HOA listed as the beneficiary.

- The owner of the EVSE, and subsequent owners, are required to pay for maintenance or replacement, as well as electricity consumption.

- The installation must be done by a certified electrician using certified EVSE.

- An HOA is free to install common-use EVSEs in common areas, and develop rules over their use.

- In some cases, an EVSE that’s designated for the use of one resident can be installed in a common area.

Another EVSE-related policy change is seen in the Los Angeles Green Building Code, which went into effect on January 1, 2011. One of the requirements is that new MUD construction building must make 240 volt, 40 amp circuits available in 5 percent of parking spaces. Compliance with this requirement is not a panacea, but offers only a partial solution.

Technology fixes

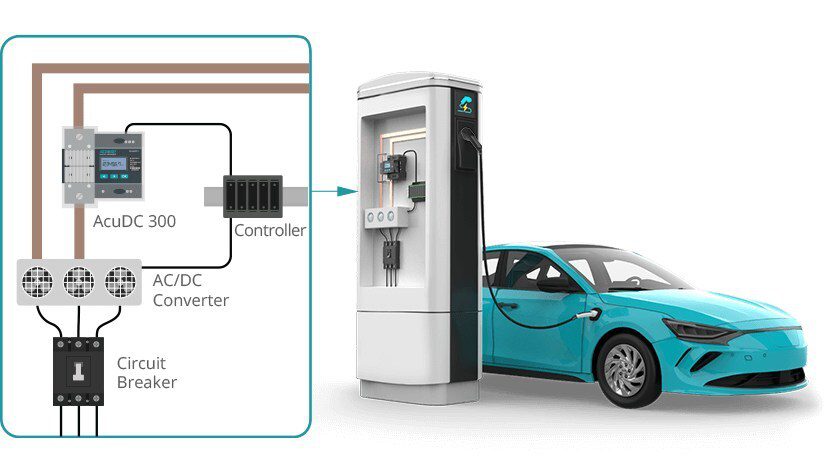

There is a risk that adding an EVSE will outstrip the electrical capacity of a parking area. It might not be the first EVSE that triggers this condition, but eventually it will be triggered as more electric car owners request EVSEs. The question is: who pays for the upgrade in the service capacity for the parking area?

One company, EverCharge, has developed a solution that avoids the need for expensive electricity service upgrades. It works by sequencing the charging of EVs, controlling all the EVSEs in a parking area, turning them on and off cooperatively to manage total electricity consumption. According to Mario Holdsworth of EverCharge, the company “bills the EV owners for our service and provides a zero-cost solution for HOAs.” That service includes a complete package of insurance, membership structure, reimbursements, and more.

An EverCharge Power Manager is installed between each EVSE and its circuit breaker. The power managers communicate with each other wirelessly, in order to sequence the charging of each car and not exceed the electrical capacity.

The company says that two large condominium buildings have chosen EverCharge to manage EVSEs. One system in Irvine, California will be installed this month. The other condominium is in San Francisco.

The system provides an automated version of a solution often discussed: shared access to EVSEs. It is conceivable that residents of a given MUD could cooperate with each other to share one or more EVSEs. But what if one car finishes charging at 3 am? Who will be up to shuffle cars around so the next in the charging rotation is plugged in? The computerized control system embedded in EverCharge can do this automatically, without having to physically move cars around.

The Multicharge SF Project

With these challenges in mind, ChargePoint (previously known as Coulomb Technologies) received a grant from the California Energy Commission to fund EVSE deployment in MUDs in San Francisco. The goal was to develop best practices and a knowledge base that will assist future EVSE deployments in MUDs. The SF Department of the Environment is focused on administration, outreach, education, coordination, and collecting survey data.

SF Environment staffers sent out a solicitation for owners and property managers of MUDs to participate, and representatives of approximately 400 buildings were contacted. Of the 400, 68 applications to participate in the program were submitted with ChargePoint-approved contractor bids.

The 68 applicants included 35 apartment buildings, 27 condominium complexes, 1 co-op, and 5 tenant-in-common buildings. They comprised 159 EVSEs, with a cost estimate per EVSE ranging from $1,800 to $16,800 – the majority falling between $3,000-5,000 per EVSE.

The program ultimately selected 37 MUDs, and 92 EVSEs were installed. The buildings chosen ranged from small, with as few as three units, to large, with 22 of the buildings containing over 100 units.

The largest project was at Park Merced, a massive complex covering 152 acres and over 3,000 units. This project became a small part of Park Merced’s long-term plan to transition into a proper sustainable housing community with integrated transit connections.

Interestingly, older housing stock did not correspond to higher EVSE installation costs. The eight buildings built before 1925 had a cost per EVSE of $3,209. The three buildings built between 1926 and 1960 were the most expensive, with a cost per EVSE of $5,349. Four buildings built between 1961 and 1980 had a cost per EVSE of $4,960, and the remaining 22 buildings, built after 1981, had a cost per EVSE of $4,327.

Why would we expect an EVSE installation in older housing to be more expensive? Because the stereotypical older housing has sketchy wiring that would require upgrades to handle the power requirements of an EVSE. While some of the buildings were described as “museums of electricity” (old wiring), others had been upgraded.

What makes the EVSE installation expensive is the actual work involved. Will the EVSE be a long distance from the power distribution cabinet, and thus require a long run of conduit? Will there be any trenches dug or other construction work? Will the power panel have to be upgraded to support more power?

What makes the EVSE installation expensive is the actual work involved. Will the EVSE be a long distance from the power distribution cabinet, and thus require a long run of conduit? Will there be any trenches dug or other construction work? Will the power panel have to be upgraded to support more power?

For the most part, EVSE installation is no different from that of any other electrical equipment, making the installation itself trivial compared to other issues around EV charging in MUDs.

Some automakers are known to be explicitly targeting customers who live in single family homes, while not targeting MUD residents. The automakers recognize that a sale to a single family home resident is more likely to result in a happy customer. With current circumstances, they believe their marketing efforts are better spent on targeting these customers.

A case in point: Richard Wiesner versus Trinity Management

A case arose in May 2012 involving Richard Wiesner, a San Francisco resident of an apartment building owned by Trinity Management. Wiesner had a brief moment of media attention when he was denied a request to plug his Chevy Volt into the power outlet next to his assigned parking space. He told the local ABC TV station, “living in the Bay Area, you just feel like you have some obligation to be as green as you possibly can,” and went on to explain the ideal convenience of having a power outlet next to his car and recharging it at home.

Photo by DrivingtheNortheast

This represents in a nutshell some of the challenges an electric car owner faces in this situation. The power outlet is right there, but the landlord says “no.”

MUDs come in many forms, from apartment high rises to condominiums. The wide range of covenants governing parking spaces makes it difficult to develop a one-size-fits-all system to enable EVSE installations. San Francisco’s MultiCharge SF project is focusing on collecting information about the real issues and eventually publishing a report. We eagerly await the findings.