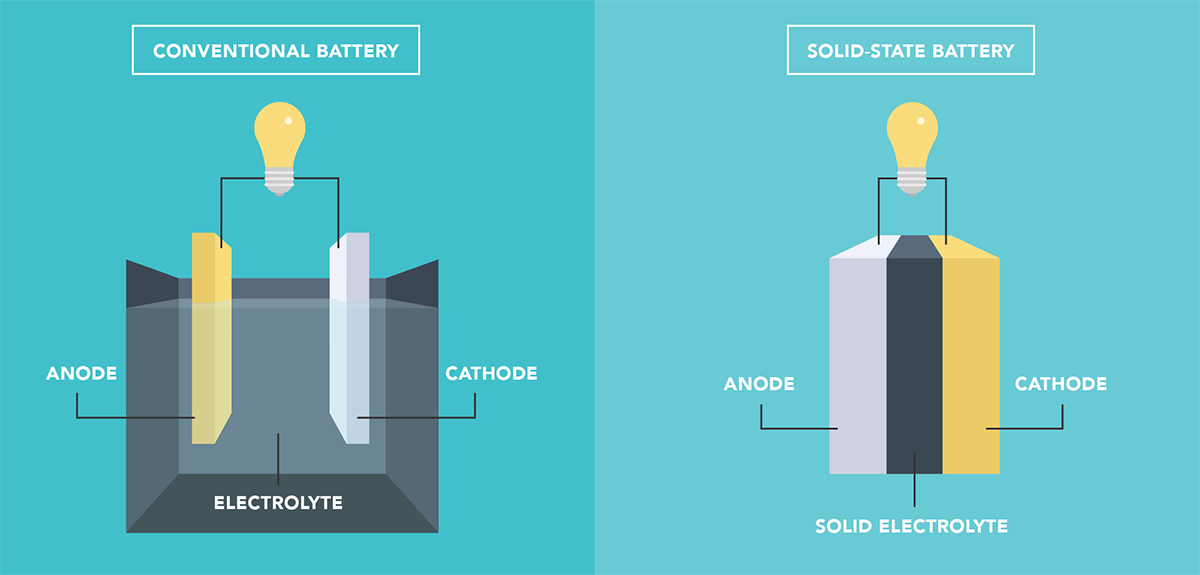

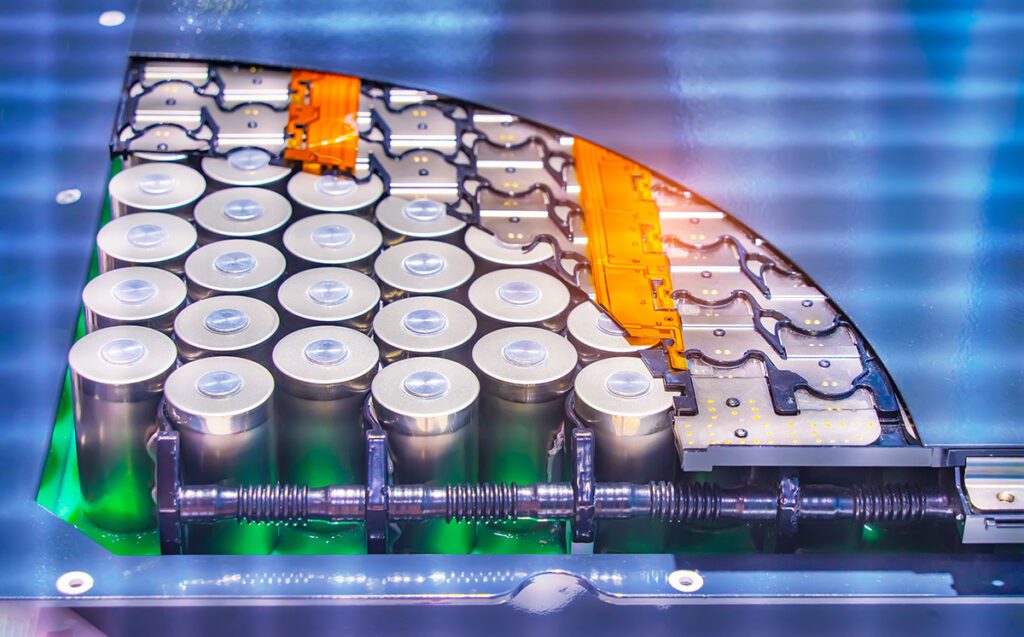

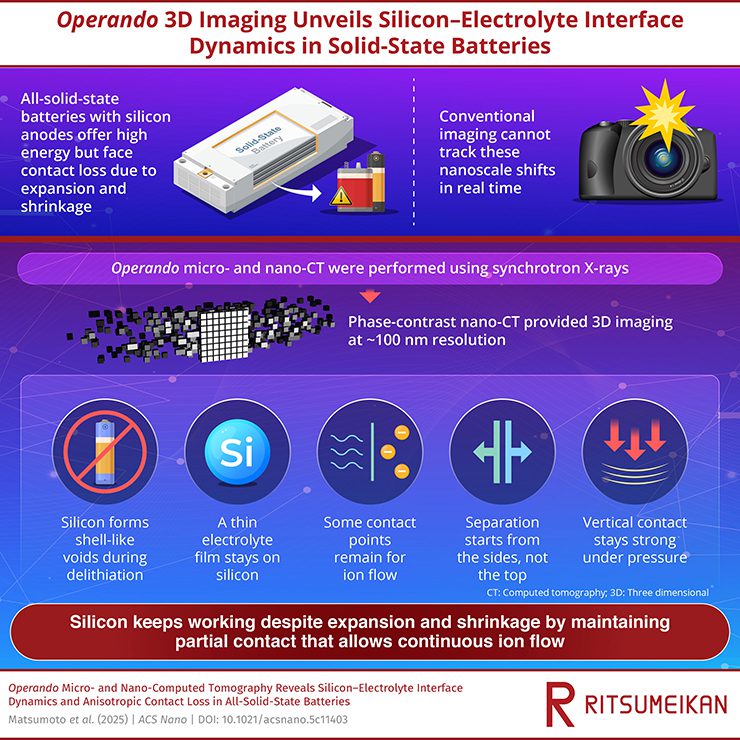

Silicon anodes can greatly boost the energy density of all-solid-state batteries, but their large volume changes often cause contact loss with solid electrolytes. Si can store more lithium than graphite, but its volume can expand by as much as 410% during charging, generating mechanical stress that cracks particles and weakens their contact with the solid electrolyte.

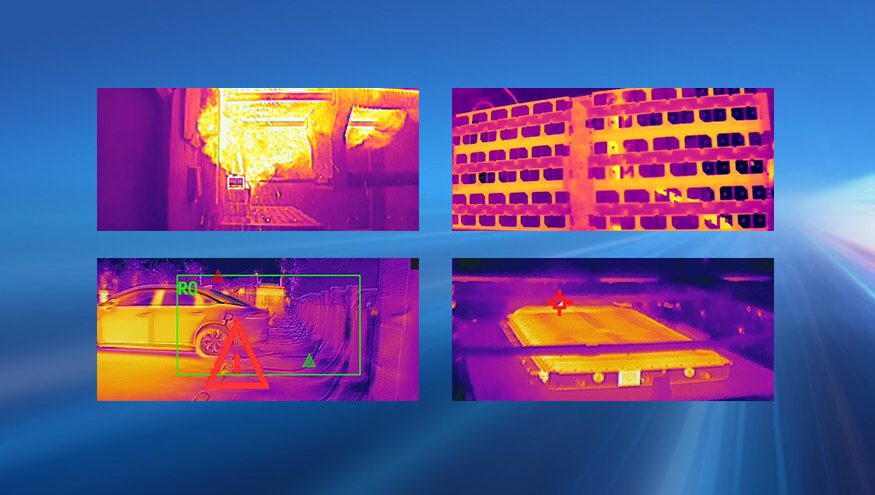

Using operando synchrotron X-ray micro- and nano-computed tomography, researchers at Japan’s Ritsumeikan University directly visualized the 3D evolution of the silicon-electrolyte interface during charge and discharge cycling. They found that even as silicon expands and shrinks, the thin, solid-electrolyte layers remain adhered, preserving partial ion pathways and enabling stable operation.

The research group, led by Professor Yuki Orikasa from the College of Life Sciences at Ritsumeikan University, reported its findings in “Operando Micro- and Nano-Computed Tomography Reveals Silicon-Electrolyte Interface Dynamics and Anisotropic Contact Loss in All-Solid-State Batteries,” published in the journal ACS Nano.

“The insights obtained in this study, including the identification of nanoscale interfacial separation phenomena and their effect on ionic transport, deepen our understanding of the chemomechanical interplay in Si-based ASSBs and provide guidance for the design of more robust, high-capacity composite electrodes,” said Professor Orikasa.

The team built a specially designed, all-solid-state cell using a sulfide-based solid electrolyte, Li6PS5Cl, and optimized imaging optics that allowed 3D visualization of the electrode’s microstructure during cycling. These operando images captured how Si particles expand and shrink, forming shell-like voids around their surfaces as they delithiate. Conventional wisdom would suggest that such voids completely isolate Si from the electrolyte, blocking ion conduction. However, the researchers observed that portions of the solid electrolyte remained attached to the Si even after contraction. These residual layers act as tiny bridges, maintaining partial ionic contact and keeping the battery functional despite significant structural changes.

At higher resolution, the nano-computed tomography data revealed that the detachment of Si from the solid electrolyte is not uniform. Instead, it follows an anisotropic pattern. The separation begins along the sides of the Si particles where the pressure is lowest, while the regions compressed vertically remain largely connected. This directional delamination creates zones of preserved contact, enabling lithium ions to continue flowing through parts of the interface. Such partial connectivity explains why the battery continues to operate efficiently after the first few cycles, even though the contact between Si and electrolyte is far from perfect.

“The findings suggest that not all interfacial separation is harmful,” the team concluded. “Partial and directionally constrained delamination can coexist with stable performance if the electrolyte retains limited but continuous pathways for ion transport.”

The researchers also point out that this study illustrates how advanced visualization tools can uncover the hidden dynamics that make next-generation energy storage systems more resilient and efficient, guiding future innovations in EV and grid-scale battery technologies.

Source: Ritsumeikan University