In the late 1990s my wife, Cathy, decided she wanted her next car to be electric.

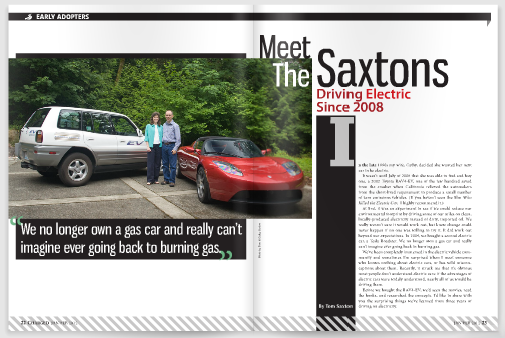

It wasn’t until July of 2008 that she was able to find and buy one, a 2002 Toyota RAV4-EV, one of the few hundred saved from the crusher when California relieved the automakers from the short-lived requirement to produce a small number of zero emissions vehicles. (If you haven’t seen the film Who Killed the Electric Car, I highly recommend it.)

At first, it was an experiment to see if we could reduce our environmental footprint by driving some of our miles on clean, locally-produced electricity instead of dirty, imported oil. We really weren’t sure it would work out, but knew change could never happen if no one was willing to try it. It did work out beyond our expectations. In 2009, we bought a second electric car, a Tesla Roadster. We no longer own a gas car and really can’t imagine ever going back to burning gas.

We’ve been completely immersed in the electric vehicle community and sometimes I’m surprised when I meet someone who knows nothing about electric cars, or has wild misconceptions about them. Recently, it struck me that it’s obvious most people don’t understand electric cars: if the advantages of electric cars were widely understood, nearly all of us would be driving them.

Before we bought the RAV4-EV, we’d seen the movies, read the books, and researched the concepts. I’d like to share with you the surprising things we’ve learned from three years of driving on electricity.

Range Anxiety

Range anxiety is the term often used for the misplaced fear of driving an electric car with a range that’s lower than what we’re used to from driving gas cars. Conquering this fear requires a shift in thinking from how many miles you can drive on a tank of gas to how many miles you drive in a day.

Today’s electric cars won’t work for everyone. Someone that has an exceptionally long commute, say 150 miles per day, isn’t going to be happy with an electric car that can only drive 100 miles between charges. That’s not range anxiety, that’s just reality.

Like the Nissan LEAF introduced this year, the Toyota RAV4-EV has a nominal range of about 100 miles. We looked at our driving and knew that we don’t drive over 100 miles very often, so we figured that we could use the RAV4-EV, with its limited range, for maybe half of our driving.

We were totally wrong. It’s more like 98% of our driving. Despite doing the math, we were surprised how much 100 miles really is. The only time we needed to drive a gas car was when we needed to be different places at the same time. Since we both wanted to drive the cool electric car, we instituted a simple rule: whoever needed to drive the farthest got to take the electric car.

Cathy’s parents were skeptical about the electric car. They thought we’d end up stranded somewhere with no charge. Shortly after we got the RAV4-EV, the alternator on Cathy’s mom’s car died, lighting up every error indicator on the dash. She had it towed to the nearest dealer and was stranded there. We were out running errands in the RAV4-EV and were down to 70% charge when she called to ask for a ride. We had plenty of charge to pick her up, drive her home and get home ourselves. The car came through for an unplanned side trip outside of our normal driving routine.

Three weeks into driving electric, and range anxiety was dead.

If you’re considering buying an electric vehicle, I recommend you measure your daily driving. Each morning, either record your odometer reading or zero your trip meter. The next morning, see how far you drove and write it down. Do this until you have a good idea how far you typically drive and how far you drive on exceptional days. If you can do your driving on 70% to 80% of a vehicle’s rated range, then that electric vehicle will probably work for you.

Do You Have to Plug It In?

It’s hard to appreciate what a nuisance gas stations are until you stop buying gas to fuel your car.

There’s the obvious problem that gas prices can fluctuate wildly which poses a real problem when you depend on gasoline to get you to work and run your daily errands. All it takes is a disturbance in some unstable country in the Middle East to threaten the world supply of oil and prices spike, turning a normal weekly expense into a genuine hardship.

The inconvenience of gassing up is harder to notice because it’s so normal. When the tank gets low, you have to make a detour and often end up running late. Working the gas pump leaves your hands smelling like gasoline for hours, something I used to hate doing on the way out to dinner.

Gas stations are outdoors, in the cold and wet. When your favorite station is busy, you end up burning more gas while waiting to creep up in line. If you share a car and the other driver drains the tank getting home instead of stopping to fill up, you get stuck with the chore when you need to drive.

None of this happens when you charge up at home overnight. People new to the concept often give me a concerned look and ask, “do you have to plug it in?” “No,” I answer, “I get to plug it in.” Instead of fueling at a gas station, sending my dollars overseas, and breathing toxic fumes, I charge at home with about the same effort required to charge my cell phone.

The Electric Experience

Internal combustion engines are amazing machines. Through a complex mechanical apparatus, they turn a rapid sequence of small explosions into circular motion that can be used to power our wheels and push us down the road. It’s great technology, but it has some limits. Typical efficiency is only about 20%, meaning that only 20% of the energy in gasoline is converted into usable mechanical power. Engines only produce high torque (acceleration) in a narrow band of RPMs. We compensate for this by putting tachometers in sports cars so the driver can shift gears to take maximum advantage of engine torque. Automatic transmissions handle this for us, but it makes for a jerky driving experience when accelerating and causes delays in response when pressing the gas pedal to go from steady cruising to accelerating when passing. Gas engines can’t produce much torque at low RPMs which is why cars stall.

We all learn how to deal with these limitations when we learn to drive and many take pride in being skilled at driving a manual transmission to get maximum performance, a particular challenge for those living in cities with lots of steep hills.

Electric motors don’t have these same limits. An electric drivetrain can be over 90% efficient. The types of motors used in electric vehicles produce torque over a broad range of RPMs, negating the need for a transmission. Starting from a stop when pointed up a steep hill is no problem. Accelerating up an onramp is smooth. Response to the accelerator pedal is instant, whether you are taking off from a stop or accelerating from 50 mph to pass.

Imagine parallel parking, facing up a steep hill, and wanting to move a few inches forward to fit in the spot. That can be a challenging task in a gas car, but it’s very easy in an electric vehicle.

I’d read about this stuff before we got our RAV4-EV, but I didn’t really understand it until I’d been driving electric for a couple of months. Now on those occasions when I drive a gas car, it’s startling how awkward it seems. Soon there will be young people learning to drive in electric cars. I suspect those people will look at driving on gasoline the same way we think of horse and buggies: quaint, but not something you’d want to do every day.

Charge Times

The single most frequent question I answer for people is “how long does it take to charge?” The answer to that question is both complex and misleading. Once you really understand how driving electric is different from driving gas, you realize it’s not even the right question to ask.

We all understand the process involved with fueling a gas car. It’s so simple and common it doesn’t even occur to us to consider the thought process that goes into it. In a gas car, you drive until the gas tank is low enough that you feel it’s necessary to gas up. You drive to a gas station and (assuming you can afford it) you fill the tank up to full. No one pops into a gas station with 3/4 of a tank to add a gallon of gas. Going to the gas station is annoying, so no one does it any more than absolutely required.

Driving electric is different. Charging is easy and convenient, mostly done at home, and requires only a few seconds of your time to plug in. You almost never do a full charge from empty to full, you just charge back up to full each night. This might take a few minutes or a few hours, but you don’t care because you don’t have to stand there while it charges.

If someone asks me how long it takes to charge the RAV4-EV and I tell them five hours, it can picture the image going through their head. They imagine me driving to the grocery store, realizing I’m running out of charge, pulling into a charging station and waiting five hours before I can go buy my gallon of milk.

That’s how it works with a gas car, but only because filling up is inconvenient but quick. With an electric car, you start every day with a full charge so you don’t run out of charge on the way to the grocery store. If an electric car won’t let you do your typical, and even exceptional, daily driving without waiting for a mid-day charge, then you shouldn’t buy that electric car.

Also, you don’t have to fill up all the way. If I drive 60 miles to the nearest shopping mall, leaving only 40 miles of range, I don’t need to wait to replenish the full 60 miles. I only need to add about 30 miles of charge to get back home with a comfortable buffer.

The RAV4-EV with a 100-mile range takes about five hours to charge from empty to full. Charging from the same source, the Tesla Roadster with an over 200-mile range takes about 10 hours to charge. If we drive each of them 40 miles, they take about the same time to charge. An electric vehicle’s charge time doesn’t depend on the size of the battery pack, it depends on how much it’s been driven since the last charge, how much is needed for the next drive, and how quickly it can take in power.

Charging Speed

Once you know the range of an electric car, instead of asking how long it takes to charge, the right question to ask is how quickly can it take in charge. As long as it charges fast enough to recharge from your typical daily drive, it doesn’t matter how long a full charge takes. Even if you drain the battery all the way to empty one day, you don’t have to get if fully charged that night. You’ll be good to go if you can pick up enough charge for your next day’s drive.

The RAV4-EV charges at a rate of about 20 miles of range per hour of charging from a special 240V charger. If I drive it 40 miles one day, it will take about two hours to charge back up to full that night. If I drive 60 miles to the mall, I’ll need to shop for about an hour and half while the car adds the 30 miles of range I need to get back home. If it’s only 40 miles to the mall, I won’t have to charge at all.

The Tesla Roadster can charge from a variety of sources, picking up at little as three miles of range per hour of charging from a regular 120V outlet, or as much as 60 miles of range per hour of charging from a full 240V/70A charging station.

Both the Nissan LEAF and the Chevy Volt charge at about five miles of range per hour from a regular 120V household outlet or about 12 miles of range per hour from a 240V charging station.

The typical US driver has a daily round trip commute of under 40 miles. For those drivers, charging a LEAF from a 120V outlet can do the job because they can pick up 50 miles of range in 10 hours of overnight charging. Say you drive 90 miles one day, get home with 10 miles of range, and charge overnight for 10 hours. In the morning, you’ll have 60 miles of range, which is more than enough for a typical 40 mile day, with enough buffer to run some extra errands if needed. If you expect to drive 80 miles every day, then charging from a 120V outlet isn’t right for you. (And really, the LEAF isn’t right for you unless you can also charge while you’re at work.)

When we bought the Roadster, we got the super duper home charger that can add 60 miles of range per hour of charging. As it turns out, that’s just silly. Instead of charging at 70 amps, we charge at 32 amps. In two years and 17,000 miles of driving, we’ve never needed to charge at more than 32 amps at home.

The only time the 70A charging has been useful has been when Roadster friends were driving through town and needed to charge to continue their journey. That’s when charging quickly matters: when you’re driving beyond your single charge range and need to pick up charge away from home during your journey.

Most EV owners don’t need to worry about charging quickly at home, as it will mostly be done at night. While most of your driving will be within your single charge range, it’s very helpful to have the capability to charge faster away from home.

So, to properly evaluate how well an electric vehicle will meet your needs you’ll need to ask two questions: how far will it go on a single charge and how fast can it take in charge (miles of range per hour of charging).

The Joy of Not Burning Gas

Prior to purchasing the RAV4-EV in 2008, we owned three gas cars. Our primary car was a 2001 Honda Insight. It got over 50 mpg and was big enough for the two of us and groceries. When we needed to carry more cargo or more than two people, we drove our 17-mpg 1996 Nissan Pathfinder. Our fun car was a 21-mpg 1995 Acura NSX-T, an incredible sports car that was a joy to drive and still got better gas mileage than the Pathfinder. Shortly after getting the RAV4-EV, we sold the Pathfinder and the RAV4-EV become our primary car, being more energy efficient then the Insight and having nearly as much passenger and cargo space as the Pathfinder. When we got the Roadster, Cathy made me wait six weeks before selling the NSX. She was worried I’d miss the NSX if the Roadster wasn’t everything we thought it would be. When the six weeks was up, I drove the NSX and realized how slow and unresponsive it felt compared to the Roadster. We sold the NSX shortly after that and haven’t regretted it a bit. We waited another year before selling the Insight when we realized we used it so little we should let someone else take advantage of a very efficient gas car.

With only a few models of electric cars available, not everyone will be able to make the switch to all electric, but millions of households in the US have multiple cars and a garage where they can charge an electric vehicle. Many of those households can replace one of their gas cars with an electric. They may think of the electric vehicle as their second car, a limited vehicle that they just use for short trips but, like us, I suspect many of them will find it quickly becomes their main car, with the gas car as the vehicle relegated to occasional long trips. If we can replace just one car in most of the multiple car households in the US, that would be a giant step toward reducing our economic dependence on oil, our political and military costs in trying to stabilize the world oil market, and the impact of our driving on the environment. Plus, it’s a better experience to drive electric than gas.

Photos courtesy of Tom & Cathy Saxton

Illustrations by Nick Sirotich

This article originally appeared in Charged Issue 1 – JAN/FEB 2012