As EV adoption accelerates, so does the frequency of battery recalls—and the operational expertise they require.

In recent months, a string of recalls from major automakers has underscored the complexities of EV battery systems. Hyundai recently pulled back a limited number of 2025 IONIQ 5s in the US after identifying a short-circuit risk linked to a faulty battery pack busbar. Ford has expanded its recall of 2022 Mustang Mach-E models with extended-range batteries owing to overheating contactors that could cause a sudden loss of drive power. And BMW has faced back-to-back recalls—one affecting more than 70,000 vehicles over a software issue that could cause the high-voltage system to shut down unexpectedly, and another targeting 136 EVs in the US for incorrectly assembled battery cell modules that could lead to power loss or fire.

In some cases, these issues can be remedied with software updates. In others, the battery needs to be removed entirely and replaced.

Unlike traditional vehicle recalls, which can often be resolved with a quick part swap, removing and replacing an EV battery can take hours and must be repeated across hundreds or thousands of vehicles—often under tight timelines. For a recent luxury EV model recall of more than 25,000 vehicles, the removal took nine hours per battery.

Once consumers are notified, an extensive technical response is mobilized. Teams of technicians, transport specialists and supply chain managers coordinate a complex operation to ensure that every recalled battery is safely handled, shipped, and then repaired, recycled or disposed of under strict protocols.

To understand the realities of this process, Charged spoke with Bryce Cornet, Senior Manager of Supply Chain Logistics at EV Battery Solutions by Cox Automotive.

We discussed what happens behind the scenes of an EV battery recall, how the process differs from traditional ICE vehicle recalls, and the safety protocols that determine where each battery ends up.

Charged: What are the first steps when a battery recall is announced?

Bryce Cornet: The first thing that is considered is whether it is a safety recall or a traditional mechanical recall.

When batteries have a safety recall applied to them, most of the time an OEM has had discussions with agencies like NHTSA and then released an announcement to customers. Customers get a letter in the mail saying the battery in their vehicle is affected by a safety recall. There could be instructions, depending on how severe the safety situation is, but for the most part it’s to explain to the customer that they need to bring their car in for battery replacement.

If the recall is large enough, it may be bucketed based on the criticality of potential failures. The OEM will have data around when the production failure happened. Some batteries may be more critical than others, and they have an idea of which Vehicle Identification Numbers, or VINs, have these batteries in them. That’s something we’re able to help with too, because we have a software system that ties into the vehicle.

Often dealers are doing these repairs for the OEM. Is the dealer prepared to take on a large number of recalled repairs? They may go from doing one repair a month to 20 repairs a month. Do they have the space to store battery packs? What are the ergonomics of moving a battery through a dealership network? Do they have the tools?

Another question is whether the recall is pack-level or cell-level. Primarily, what we deal with are module- and cell-level recalls. In that case, the whole battery pack is removed from the vehicle and shipped to us, either for module replacements—maybe we can find the critical module and replace it and certify it—or it could be that the full battery pack needs to be re-cycled, in which case we do disassembly operations to make it safe to recycle.

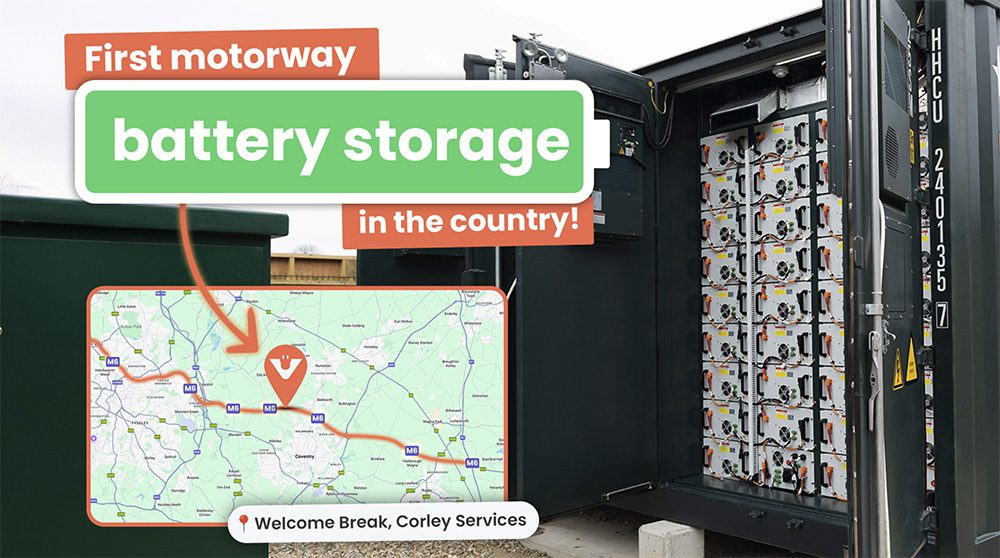

On top of disassembly and recycling, there is a storage component to consider. Some of these battery packs may be held for a certain amount of time, but they need to be held safely.

Our warehouses at EV Battery Solutions have high-pressure fire suppression systems. We support the dealer in getting batteries away from the dealership as quickly as possible, because they often don’t have a lot of extra storage for battery packs. The important thing is getting the pack and storing it if we have to, or getting it quickly to recycling, to get rid of any type of risk.

Charged: How is transportation handled, given the risks of shipping large lithium-ion batteries?

Bryce Cornet: EV batteries are packaged more robustly if it is a safety recall. A portion of this is planning, to safely transport a battery from a dealership or from distribution sites. That battery has to move through public ecosystems on trucks.

When a safety recall hits, the battery falls under a hazmat regulation in 49 CFR with the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, PHMSA, which states if the battery is damaged, defective or recalled, it cannot be transported by air or other means. We’re passionate about making recycling as close to a dealership as possible, because you don’t want to transport batteries far that potentially could have safety recalls.

Charged: Can you walk us through the logistical process of removing and handling a recalled battery?

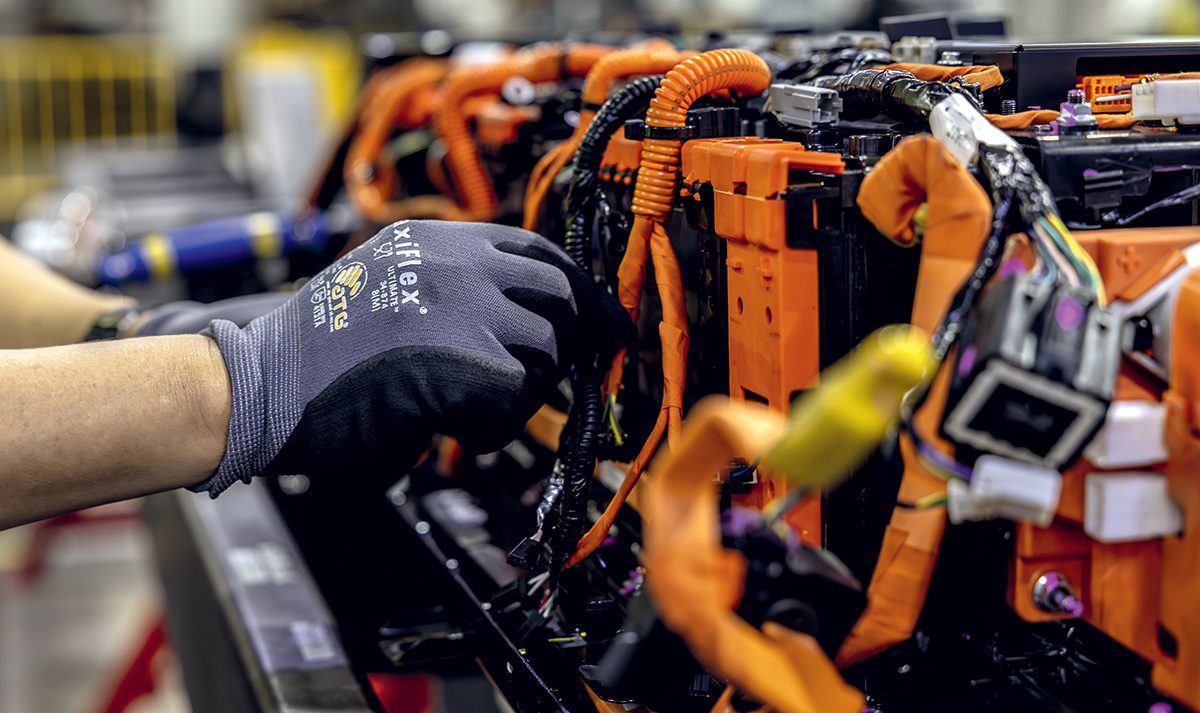

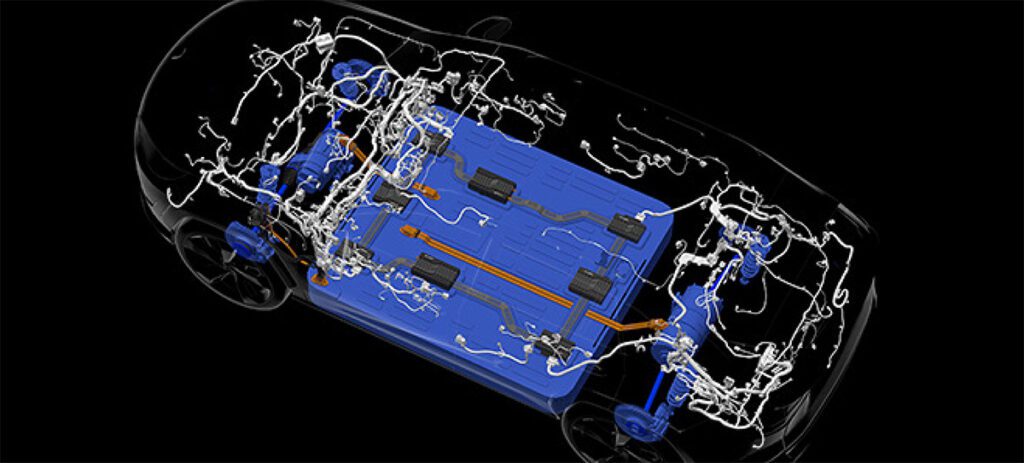

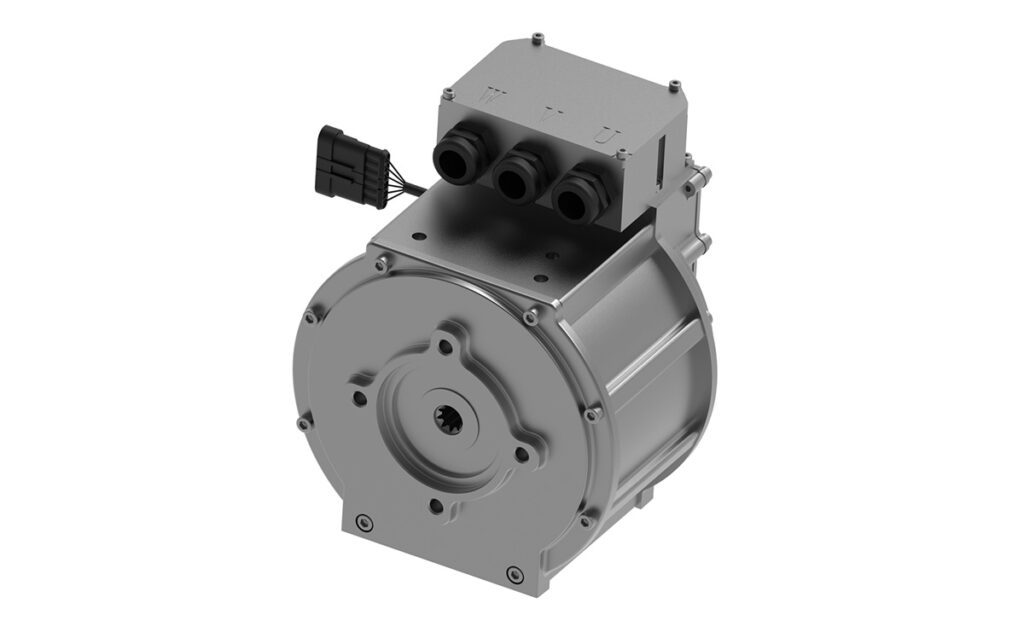

Bryce Cornet: The process varies based on the OEM, because every OEM has their secret sauce for how the battery fits into the vehicle. The form factor is different. You’re often dealing with high-voltage connections, and it may not be easy to get to them to pull them out.

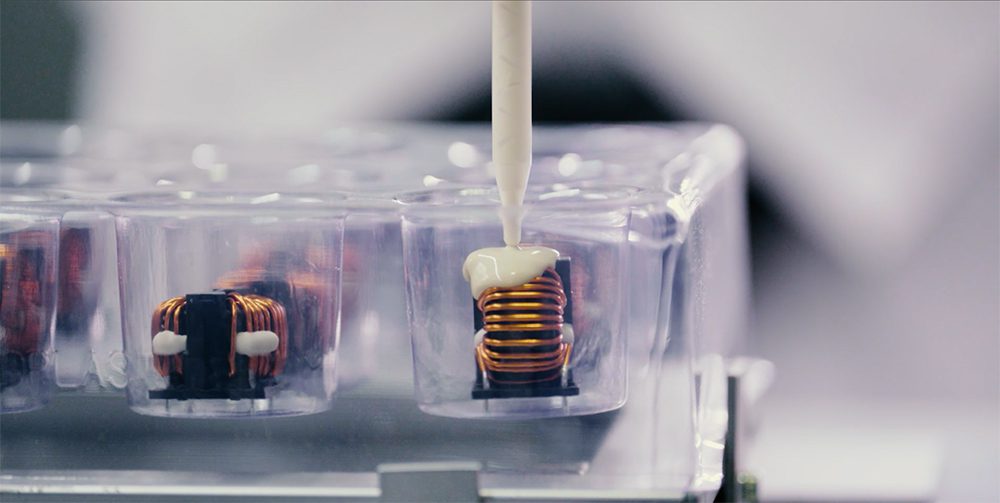

One thing that we often run into, in addition to understanding how difficult it could be for dealers to remove that from the vehicle, is simply when we get it to our sites, there’s another layer of complexity, depending on how the battery shell mounts over the modules. Is it sealed with a glue? Is it bolted down and sealed?

We have to account for the time it takes to do the disassembly-to-recycling option, because often there’s a rush to get these batteries off the road and get them recycled quickly. That can be quite the undertaking, especially as it can take anywhere from four to nine hours to fully disassemble a battery pack.

Charged: What are the biggest safety risks technicians face during battery removal, and how are those managed?

Bryce Cornet: The biggest risk is that you’re dealing with something that has charge within it, which is somewhat different from pulling an engine out. You’re having to work around high-voltage cables. There is a process to limit the voltage on the pack before they work on it, which should be a part of training.

Personal protective equipment, PPE, while they’re doing the job is likely different from traditional repairs and is important. And then after you remove the pack you don’t want to store the battery pack outside.

Depending on what may be communicated by the OEM, if it is a safety recall and there are risks, you have to consider storage and packaging. You want to make sure that it’s packaged in compliant packaging and not left on a pallet outside. There are also requirements to protect the environment that the dealer would need to know.

Charged: Are there enough skilled technicians in the industry to manage the process?

Bryce Cornet: Part of the safety aspect is safe scaling. We often have to train, hire and rehire to stand up more disassembly base. The dealer may also have to dedicate more people and more bays to these repairs, because that’s the quickest way to address long repair times.

Every time we’ve done a recall, we’ve had to hire new people that may not have been involved with EV batteries before, and that’s a risk. You have to be on it with operating instructions, having safety meetings every morning, and training your team before turning them loose on potential repairs. Dealers face the same issues with getting new EV technicians.

The number is growing, but it’s not necessarily at the point where every OEM is happy with the number of EV-certified techs.

We have an initiative inside Cox that is training all of our Manheim Auction sites to be EV-certified. Dealers are doing the same thing and that’s getting better. But finding high-quality, good talent to work on EVs can be a challenge—it is a difference from ICE. You see a lot of ICE technicians moving over to EVs, because some OEMs are adding more EVs to their fleets.

Charged: How does an EV recall differ from an ICE recall?

Bryce Cornet: One thing is the size—the battery can be quite large. One of the recalls we supported was a battery pack that was about 1,000 pounds. It was about 1,800 pounds in a crate in total. You have a dealership inserting an item that may be five times the size of the engines and transmissions they’re used to dealing with.

And that leads into other factors that are different for EV batteries. It goes all the way down to logistics. Carriers are used to moving all kinds of cargo, not just batteries. We need to educate the carrier to take precautions when they’re handling a battery.

There are technical requirements when we take an order. A dealer will contact us to say they have a vehicle down and need a battery. There is specific information we need to take from the dealer about the battery that is different from a transmission.

On a transmission, you’re looking at mileage as an indicator of health. But for batteries, you are looking at mileage, but you’re also looking at state of charge, how much percentage charge is in the battery. That affects how the OEM and how we interact with the battery when it arrives.

When we get a battery in, we’re often assessing if it’s good enough to go back into a vehicle or not. Is it safe? Are there things we can do to repair it, or does it need to go to recycling? There are different technical requirements for EVs, for us to make a decision on its criticality.

Charged: How do you decide whether it’s repaired, recycled or scrapped?

Bryce Cornet: You wouldn’t want to find out that a vehicle that was once a part of a safety recall ever has a battery that is part of another recall. Most of the time these batteries—the full packs—are disassembled and recycled immediately.

When we take in a battery, we get a core of varying health. The dealer doesn’t know of its health, usually, and we transport it here to diagnose it. We run a series of resistance measurements and voltage checks to get a baseline of what we’re looking at. Those baseline measurements are often partnered with diagnostic trouble codes, or DTCs, that tell us if there’s a low cell, a dead cell, or something specific.

Enough of that data leads us to a direction to tell if it is a good repair. If it has this DTC and these readings, we can potentially repair it. If it falls outside that window, we may have to recycle it.

At one time, we were manufacturing our own second-life energy storage systems. We’ve since stopped, but we do support other entities and OEMs with finding and testing battery cores to potentially allow them to do second life.

What we’ve often found difficult is that, to be used for second life, a battery has to be in a sweet spot in between being good enough to go back into a car or bad enough that it needs to be recycled. And as profitable as recycling is becoming, for a lot of OEMs and for recyclers, there’s less of the second use happening.

Charged: What’s the biggest recall you’ve been involved in?

Bryce Cornet: The biggest recall affected about 150,000 vehicles in the US and Europe. My team had been doing 200-300 battery shipments a month, and at the peak of this recall we were doing about 600 battery shipments a day from a site in Detroit and a site in Oklahoma City.

We were shipping out new batteries and getting back the bad batteries. These batteries weighed 1,500 pounds, and there was a process in which we had to move each battery from one crate to another before we could ship it. We had workstations with cranes, and we built a whole process where it was like a pit stop for a battery. We had about four people under that crane and they all had their job. The same thing was done for the shipping process to speed up how many we were doing.

We had a timeline of how quickly this specific client wanted the recall completed. We reduced our fulfillment times from about 20 minutes per battery pack to about five minutes. There were software enhancements that we did to make it more automated. We developed a Quick Connect system to lift the battery pack out that saved five minutes alone. In these large peaks of volume, you start to see a lot of innovation happen.

Charged: Are you seeing innovations in robotics or AI that could be incorporated into the process?

Bryce Cornet: It could be valuable in assessing a battery for damage when it’s brought in. We’re also looking into robotic automation to limit the risk to technicians from having to pull modules out of the battery, and cut out any issues with human error that could happen with tedious tasks like replacing modules.

Charged: As commercial EV adoption increases, how does that potentially affect a big recall?

Bryce Cornet: We have a lot of partners where we deal with battery packs as large as 4,500 to 10,000 pounds, where you’re touching some of those commercial applications.

We have an efficient model to deal with scaling for a recall. But any time that happens we run into issues like truck availability. Moving these large battery packs requires specific types of logistics or carrier transport—specific trailers to move the battery on. That could strain the supply chain, because it’s not traditional for those trailers to be used in high volume.

We’re knowledgeable about that now, because we’ve faced it, but in a high volume we would have to work with our partners to make that change.

Charged: As EV adoption grows, do you expect recalls to become more frequent, or could the technology develop in a way that recalls become less likely?

Bryce Cornet: It’s hard to say. It is true that as the sample size grows, we could have more recalls just from having more EVs on the road, or OEMs trying more things.

But what’s interesting is the changing of chemistries. A lot of OEMs are talking about LFP. The term solid-state is thrown around a lot, and there are a lot of different potential chemistries and ideas. How does LFP affect potential recalls? Does it make it better or worse? Is it easier to handle LFP than the traditional NMC packs? We don’t have the answer yet, but as some of these OEMs change their chemistries, we’ll quickly find out.

This article first appeared in Issue 73: July-September 2025 – Subscribe now.