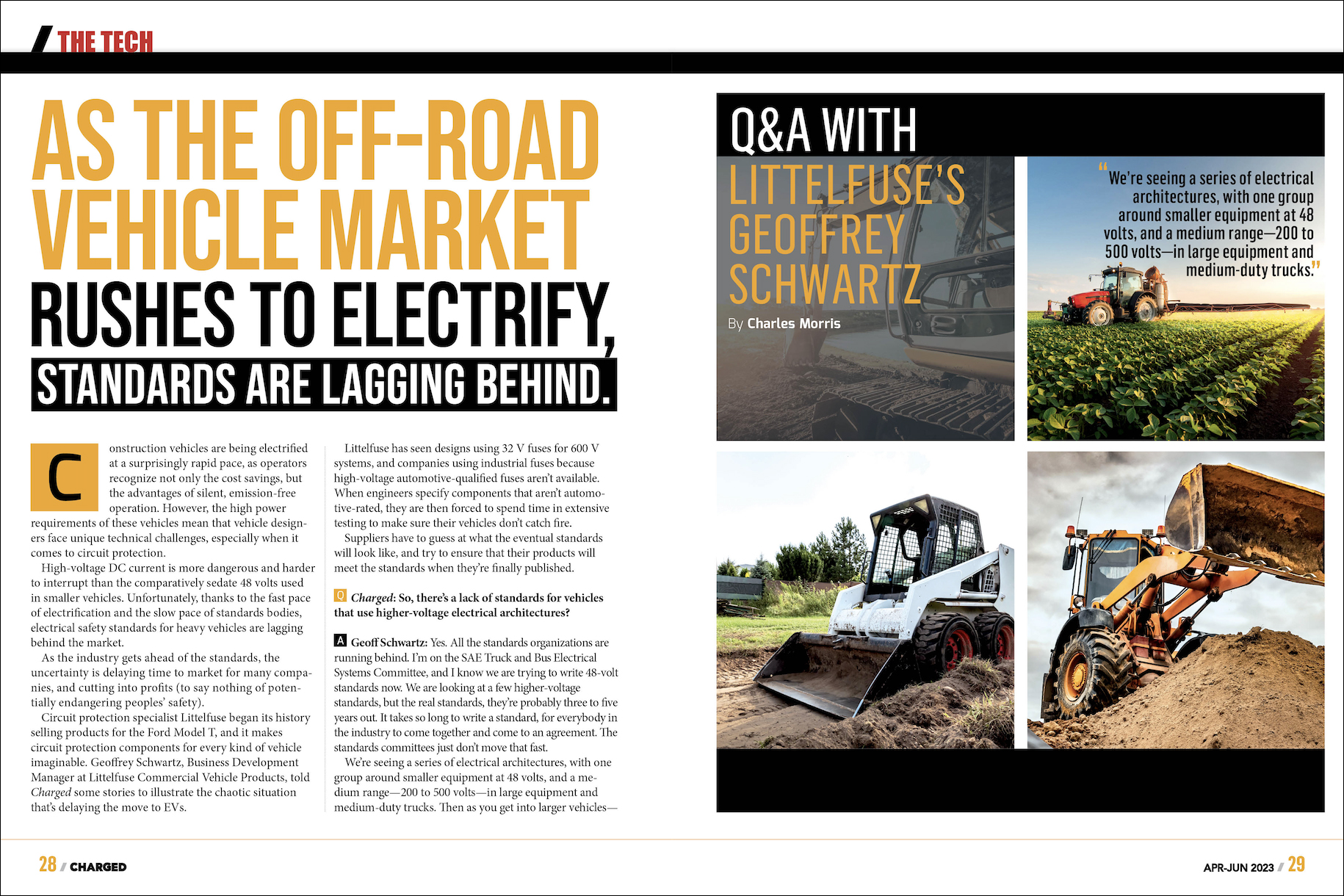

Q&A with Littelfuse’s Geoffrey Schwartz

Construction vehicles are being electrified at a surprisingly rapid pace, as operators recognize not only the cost savings, but the advantages of silent, emission-free operation. However, the high power requirements of these vehicles mean that vehicle designers face unique technical challenges, especially when it comes to circuit protection.

High-voltage DC current is more dangerous and harder to interrupt than the comparatively sedate 48 volts used in smaller vehicles. Unfortunately, thanks to the fast pace of electrification and the slow pace of standards bodies, electrical safety standards for heavy vehicles are lagging behind the market.

As the industry gets ahead of the standards, the uncertainty is delaying time to market for many companies, and cutting into profits (to say nothing of potentially endangering peoples’ safety).

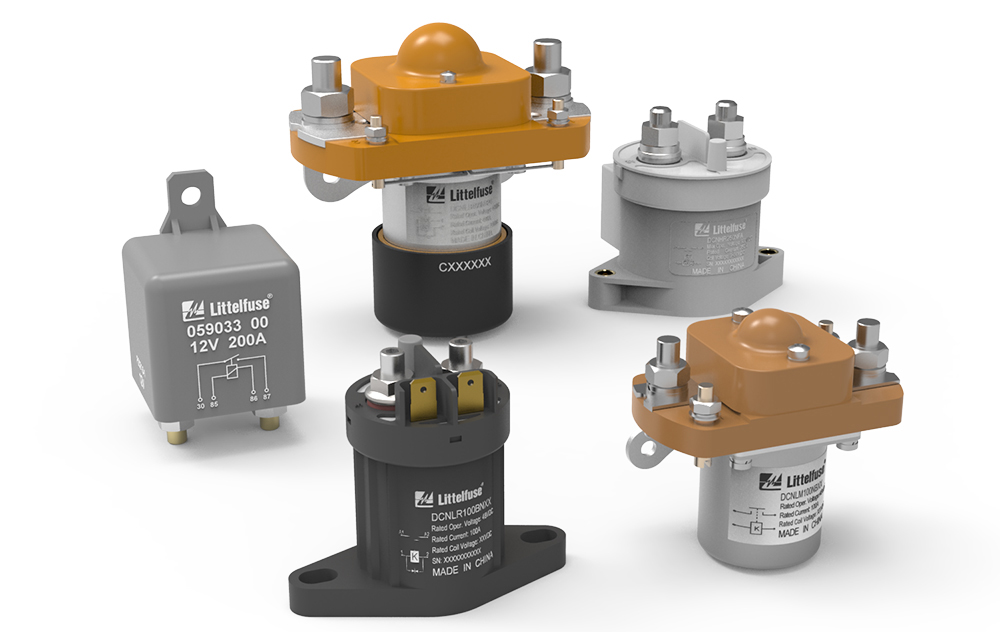

Circuit protection specialist Littelfuse began its history selling products for the Ford Model T, and it makes circuit protection components for every kind of vehicle imaginable. Geoffrey Schwartz, Business Development Manager at Littelfuse Commercial Vehicle Products, told Charged some stories to illustrate the chaotic situation that’s delaying the move to EVs.

Littelfuse has seen designs using 32 V fuses for 600 V systems, and companies using industrial fuses because high-voltage automotive-qualified fuses aren’t available. When engineers specify components that aren’t automotive-rated, they are then forced to spend time in extensive testing to make sure their vehicles don’t catch fire.

Suppliers have to guess at what the eventual standards will look like, and try to ensure that their products will meet the standards when they’re finally published.

Charged: So, there’s a lack of standards for vehicles that use higher-voltage electrical architectures?

Geoff Schwartz: Yes. All the standards organizations are running behind. I’m on the SAE Truck and Bus Electrical Systems Committee, and I know we are trying to write 48-volt standards now. We are looking at a few higher-voltage standards, but the real standards, they’re probably three to five years out. It takes so long to write a standard, for everybody in the industry to come together and come to an agreement. The standards committees just don’t move that fast.

We’re seeing a series of electrical architectures, with one group around smaller equipment at 48 volts, and a medium range—200 to 500 volts—in large equipment and medium-duty trucks. Then as you get into larger vehicles—trucks, tractors, large construction equipment—that stuff’s all going to 800 volts up to 1,000 volts.

We’re seeing a series of electrical architectures, with one group around smaller equipment at 48 volts, and a medium range—200 to 500 volts—in large equipment and medium-duty trucks.

When will they need to go higher than 1,000 volts? I’m pretty convinced that’s a 2035 problem. The EPA requirements are that commercial vehicles will have to be 40% electric by 2035. And there’s 40% of the Class 8 market and the medium-duty market that [drives] under 250 miles a day. With current technology, they can hit those numbers. You can get 250 miles a day even with a full load nowadays, so that technology is there for right now. But the problem is going to come in 2035 when they exhaust that 40%. Then you have to look at longer-range vehicles, and that’s when I suspect you’re going to see them go above 1,000 volts, because they have to pack more power into the device.

A couple of things are holding that up right now—number one is the power electronics. Most automotive power electronics are maxed out around 1,200 volts. You’re starting to see some creep up to 1,500, 1,800 volts, but most of them, and most of the volume and affordable ones, are 1,200 volts and under. They can’t go much above 800 to 1,000 volts in battery technology with their electronics only at 1,200 volts.

Charged: Would you say the biggest standards gap is in safety best practices?

Geoff Schwartz: Yeah, things like what’s the proper spacing of wiring and stuff like that. What do you need for gapping in the wiring, and what are the connectors you need at that level? And then there’s interoperability and all those standards that we take for granted in the 12- and 24-volt world. They don’t really exist in the 800-volt world.

Right now I’m working on a committee where we’re defining the standard for an ePTO (electric power take-off) connection. We’re talking about the physical connector, but there’s also the communication side of things, the electronic handshaking routine that has to take place—when you plug this thing in, it’s got to acknowledge and say, Okay, I’m connected correctly, and then turn on the power. With the HVIL [high-voltage interlock], you’ve got to turn the power off when you pull the plug out of something.

One of the things that standards organizations do is try and make it about the interface and about the performance rather than the actual design, so that there’s some freedom for companies to find a base for competition. As long as they are interchangeable, what you do with the rest of it is a competitive advantage.

Charged: Do the same standards bodies oversee on-highway stuff?

Geoff Schwartz: Yeah. The SAE committee covers on- and off-highway. There are specialty committees that cover special areas of off-highway, but mostly they kind of count on the truck and bus committee to write the electrical standards, so there are rarely separate standards for those things. And there’s enough [overlap] between those organizations in membership that we share information nicely and we try and work together.

It’s the Wild West. A lot of people out there are running industrial fuses in vehicles. And yeah, they’ll work, but industrial fuses are not built for vehicle-based vibration and shock.

Charged: How are vehicle designers dealing with the lack of standards? And what do you recommend to designers right now that are tasked with designing these systems?

Geoff Schwartz: It’s the Wild West. A lot of people out there are running industrial fuses in vehicles. And yeah, they’ll work, but industrial fuses are not built for vehicle-based vibration and shock. They’re built to go in a building, so they’re just not capable in a lot of cases of maintaining life in a vibration situation, which is typical of a vehicle.

As for designers, find somebody who knows what they’re doing and work with them. There are any number of suppliers out there who have the expertise, who are willing to work with you. Talk to them early, bring them on board, make them a partner. They’ve brought experience in from other people. They’ve been doing this for a long time. That’s probably the best advice I can give: Find a supplier partner and bring them in.

The biggest problem with the lack of standards is that it’s hard for suppliers. It’s hard for OEMs to figure out what to make, and therefore everything is essentially custom. So a lot of this stuff ends up costing more because it’s one-off. It’s also very low-volume right now, so that tends to drive the cost up as well. Standards will help drive consistency, and they’ll drive volume improvements and cost improvements.

Charged: I imagine it affects speed to market as well.

Geoff Schwartz: Of course it does, because everything has to be customized for that particular OEM. This one’s doing it a little bit differently than that one. We do high-voltage PDMs [power distribution modules], and everybody keeps coming in asking for it off the shelf. But nobody wants it off the shelf: “Mine’s a little different. Can’t you do something a little bit differently?”

Charged: How is Littelfuse trying to bridge the gap between the demand for products and the lack of standards?

Geoff Schwartz: We’re already out there in the market with all kinds of products, and the standards are well behind. We’re starting to bring components out now that are getting up into the 1,000-volt realm. The testing involved, because the energy levels are so high, just takes time. We are still working on getting our 1,000-volt fuses out. Once you have the design done and you have it in production, there’s about a year’s worth of testing we need to do for every single one of the [voltage] values to get it qualified.

There’s a 500-volt standard for fuses right now. There’s no 1,000-volt standard. So we’ve taken that 500-volt standard that we helped write and we’re extending it up to 1,000 volts. We’re pulling stuff in from ISO standards, from OEM standards, and trying to pick worst-case of everything. If we can hit worst-case in everything, we will be able to meet everybody’s standards. That’s kind of what we’re designing to.

Charged: I understand you saw a huge variety of electrified vehicles and industrial equipment at the recent CONEXPO.

Geoff Schwartz: I was surprised—I thought that it was going to be mostly small equipment, but there was a lot of mid-sized to larger equipment that was also going electric, including some really large stuff for mining. Probably one of the fastest things out there going electric is underground mining, because one of the big problems is, when you have diesel equipment down in a mine, how do you get all the fumes out?

Small construction equipment is tending to move to 48 volts, for two reasons. Number one, they can get a full day’s work out of a 48-volt battery pack, so they don’t need to go higher. And at 48 volts, they’re below that 60-volt threshold and don’t have to have as much protection and guarding because it’s not considered to be a lethal voltage level.

The other thing is they’ve got a lot of existing infrastructure already built for the material-handling industry. There’s a huge number of 48-volt forklifts and things like that and they’re stealing components from those areas to build their products. Forklifts are a pretty high-volume business in our realm. Not like cars, but they make several hundred thousand forklifts a year, easily—maybe worldwide, over a million. That’s a higher-volume product and that tends to drive lower prices, so they’re using those 48-volt parts, components and architecture.

We’re seeing more and more movement towards electric in construction, and that’s happening for a couple of reasons. Number one, it’s a lot better, particularly when you’re working indoors or when you’re working in an urban environment. Also, it’s a maintenance issue. For those vehicles, maintenance is key. If your car is not working—oh, that’s a pain, but I’ll use the other car or I’ll take the bus. If your excavator or your loader is not working, you don’t make money that day. So maintenance and uptime is really key and electric vehicles are better for that in this market.

Bobcat recently introduced a completely electric vehicle. They even got rid of all the hydraulics. They’re replacing hydraulic cylinders with electric actuators. The hydraulics in those vehicles are usually the number-one maintenance problem, so they are eliminating one of the biggest problems. You would think they can’t get enough power out of them, but they can. Using screws and gearing they can match hydraulics.

We have been saying that a lot of the big construction equipment wasn’t going to go BEV. The work cycle is longer and tougher, and charging becomes an issue. You can charge a small piece of construction equipment on a mobile charger or a mobile battery, but those bigger pieces of equipment take a lot of power to charge and they’re sitting out in a field. So I think the small ones are going to go electric fast, but the big ones are going to go electric slower.

One interesting problem that we have in these EVs that you don’t necessarily have in the diesel ones is that because they’re lighter weight, with fiberglass and all kinds of lightweighting, where do you ground the thing? Grounding becomes a problem, so we’ve actually released a new series of grounding boxes for customers to be able to consolidate ground.

We were expecting the heavy truck market to electrify a whole series of their auxiliaries and take the loads off the motor. What we’ve heard is they’re going to skip that step entirely and go straight to BEV.

Charged: Are you seeing a lot of auxiliary systems being electrified on those large systems?

Geoff Schwartz: Not really yet. I’m a little surprised. We were expecting the heavy truck market to electrify a whole series of their auxiliaries and take the loads off the motor. What we’ve heard is they’re going to skip that step entirely and go straight to BEV. There’s a new greenhouse gas requirement on large vehicles for 2027 engines, and California’s adopting that next year. We thought that was going to drive a lot of 48-volt stuff, but everything we’re hearing now says they’re going to skip right by that and go pure BEV.

Charged: Is there any other commercial off-highway stuff that you think is a fast-growing market?

Geoff Schwartz: I’ve seen a lot of interest in small farm tractors. I know that Case New Holland has launched an electric tractor, and Monarch is going electric. Particularly for small and specialty farmers where they’re working in tight with the crops. There’s a company called GUSS that does a fully autonomous sprayer, and now they’re bringing an electric version out as well.

I’ve seen a lot of small equipment, a lot of harvesting assist equipment. There’s a company called Burro that makes an electric crop hauler. It runs from where the picker is working to a central location—the picker is hand-picking specialty crops, and the Burro is right by his side, he loads it up, so he can just concentrate on picking.

We’re also seeing interest for hybrids based on digestive materials. For instance, a farmer could take all his scraps and put them into a digester, make his own fuel and use that to run a hybrid tractor. Case New Holland brought out a methane-powered tractor that [runs on methane] made from farm waste.

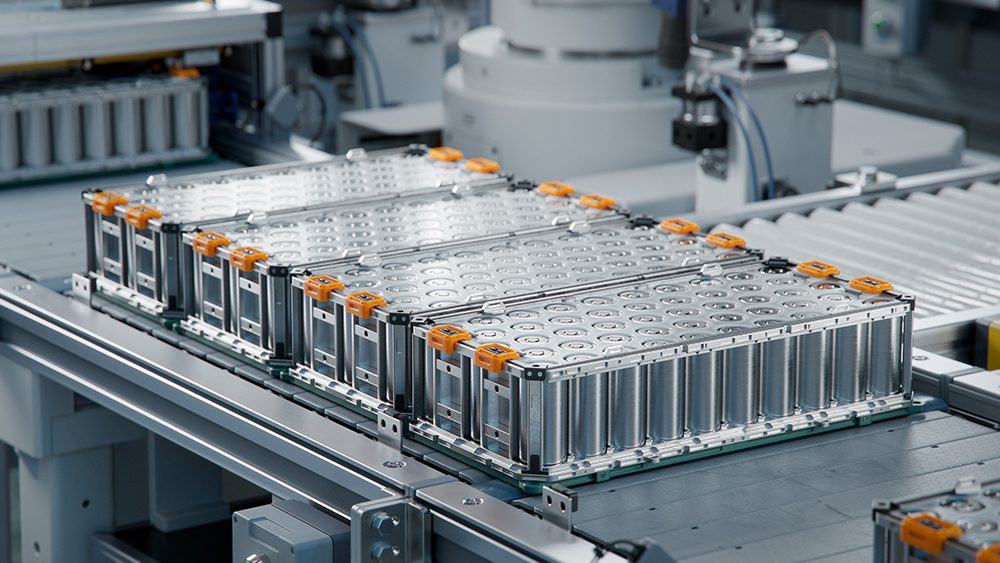

Littelfuse recently expanded its lineup of DC contactors to support next-generation commercial EVs

The other thing of course is that drivers love them now, which is fantastic. We hear comments like, “It’s easier on me, less vibration, less noise. I don’t come home smelling like diesel. I don’t come home as worn out and tired.” In the truck market, driver retention is a really big issue, because there’s just not enough truck drivers out there. If they’re not getting treated right, they can move relatively easily, so you want to retain your drivers.

Every one of the major OEMs is launching an electric truck series. The primary customers right now are the ports—Port of Long Beach, Port of Los Angeles—and the ports around the country are usually in urban environments. Transporting goods out of that environment tends to have an overly heavy effect, particularly on less opportune communities because they’re kind of built around the port, so they’re very sensitive to that pollution.

Therefore, a lot of electric and hydrogen vehicles are being brought into that market quickly. In most cases they’re running from the port, 50 or 100 miles to a warehouse and then running back to the port, back and forth. They could do three, four runs a day without a problem, without having to recharge. So those vehicles will probably go electric pretty quickly.

The other market that’s probably going to go electric quickly is refuse. Garbage trucks. You’re operating close in neighborhoods, so the quiet is a huge advantage, and you have room to have a pretty good-sized electric actuator on a garbage truck because it’s a bigger vehicle. And also, huge amounts of regenerative braking going on. They stop, start, stop, start, and because they’re doing that, they’re running that electric motor in a range where it’s very efficient in that low end of the torque band.

Charged: In terms of regulations, what are the biggest ones driving the market in the commercial space?

Geoff Schwartz:The MOU is an agreement between California and several other states that are ramping up the requirements for zero-emission commercial vehicles, with the goal to be completely emission-free by 2050. I think it’s gotten up to 17 states total now. That’s for new purchases—the lifetime of a truck is usually at 15 years plus—seven or eight years in the primary market and up to 10 years in the secondary market.

That’s one of the biggest ones, and there’s also a couple of big California regulations. California is shortly going to outlaw the use of diesel engines in transportation refrigeration units. The reefer boxes that are up on trailers or trucks, they’re going to have to go all-electric. Construction equipment, lawn and garden equipment is going electric in California as well. Shortly they’re going to eliminate the ability to buy gas mowers and stuff like that.

Now California just actually moved it up 10 years. They said they want 100% of commercial vehicles to be zero-emissions by 2040. I have doubts whether we could hit that. I think we could hit 50, 60, 70%. But when you get into longer-range vehicles, the problem is still going to be infrastructure.

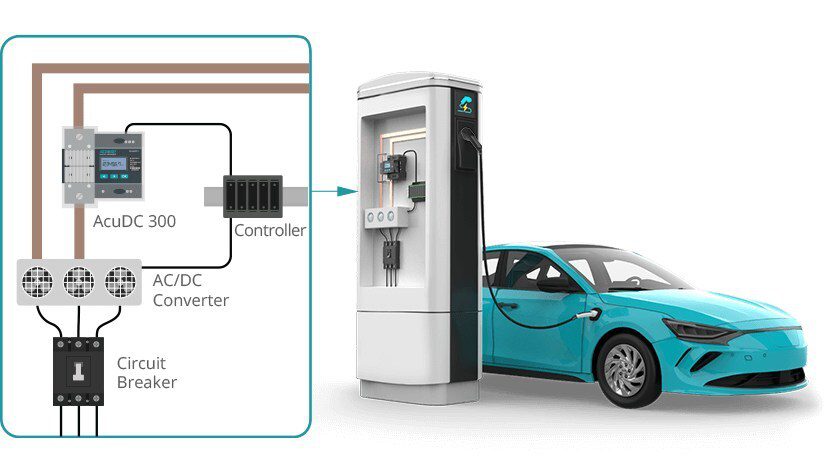

You think it’s hard to charge a car? Think about how much energy you have to pump into a truck. The Megawatt Charging System standard is intended to charge a Class 8 truck in 30 minutes. It’s capable of up to 2.2 megawatts. It’s a huge water-cooled cable. It’s a lot of power. I think the truck technology is going to be there to do it, but I’m not sure the grid will get built out fast enough to do it on schedule.

This article appeared in Issue 64: April-June 2023 – Subscribe now.