Stanford researchers have invented a new technology that could eliminate thermal runaway in high-energy-density batteries. Thermal runaway refers to a chain reaction in which an increase in temperature causes further increases in temperature and uncontrollable release of energy.

In “Fast and reversible thermoresponsive polymer switching materials for safer batteries,” published in Nature Energy, Professor Zhenan Bao and her colleagues describe a lithium-ion battery that shuts down before overheating, then restarts when the temperature drops.

“People have tried different strategies to solve the problem of accidental fires in lithium-ion batteries,” said Bao. “We’ve designed the first battery that can be shut down and revived over repeated heating and cooling cycles without compromising performance.”

Techniques that have been used in the past to improve battery safety include adding flame retardants to the electrolyte and smart batteries that provide a warning before things get too hot.

“Unfortunately, these techniques are irreversible, so the battery is no longer functional after it overheats,” said study co-author Yi Cui. “Clearly, in spite of the many efforts made thus far, battery safety remains an important concern and requires a new approach.”

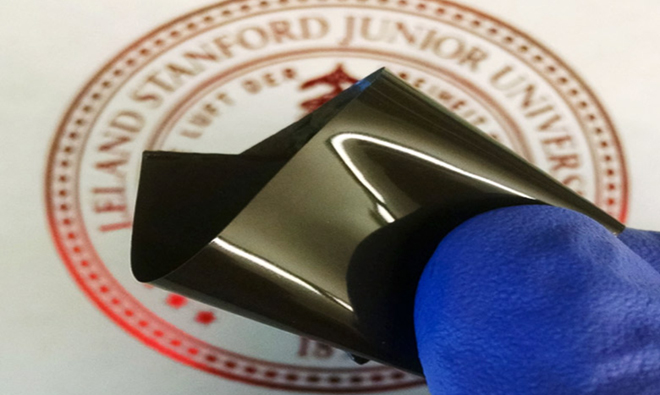

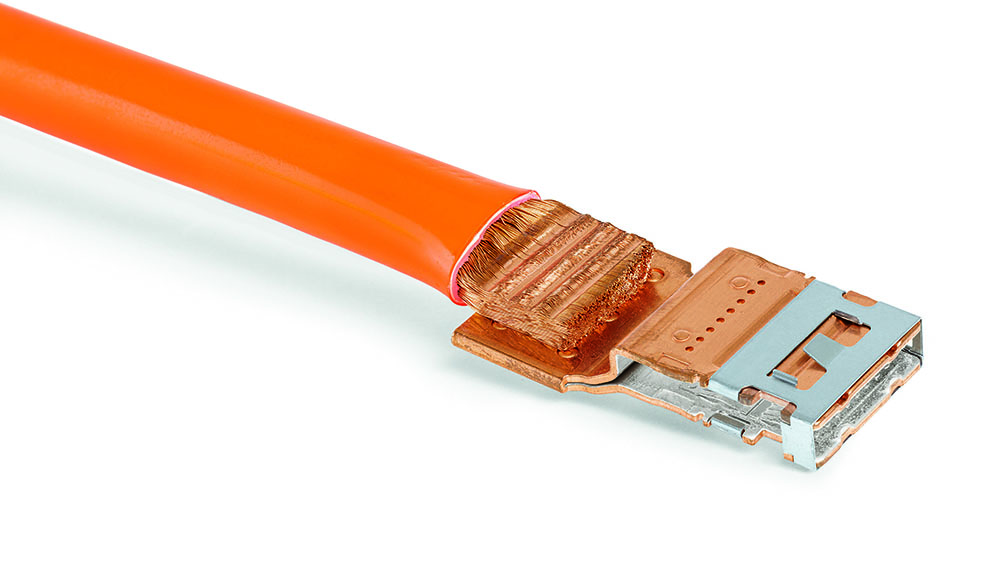

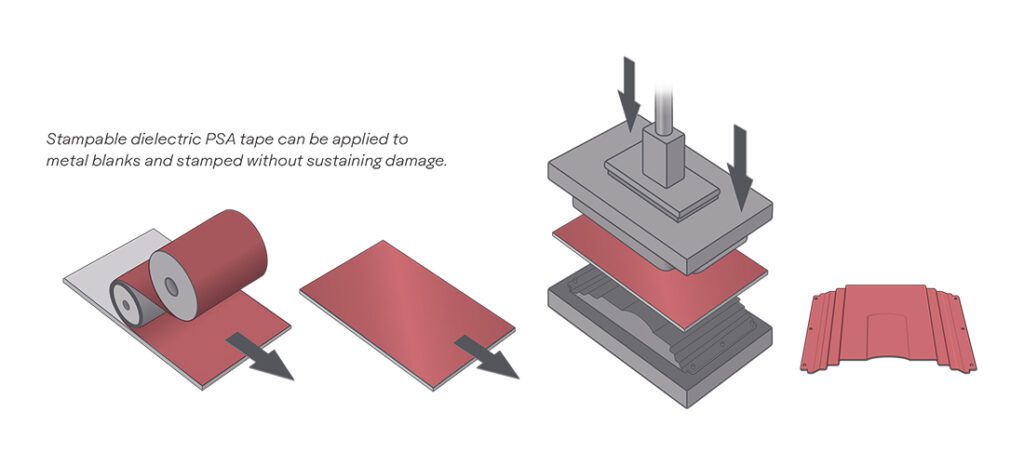

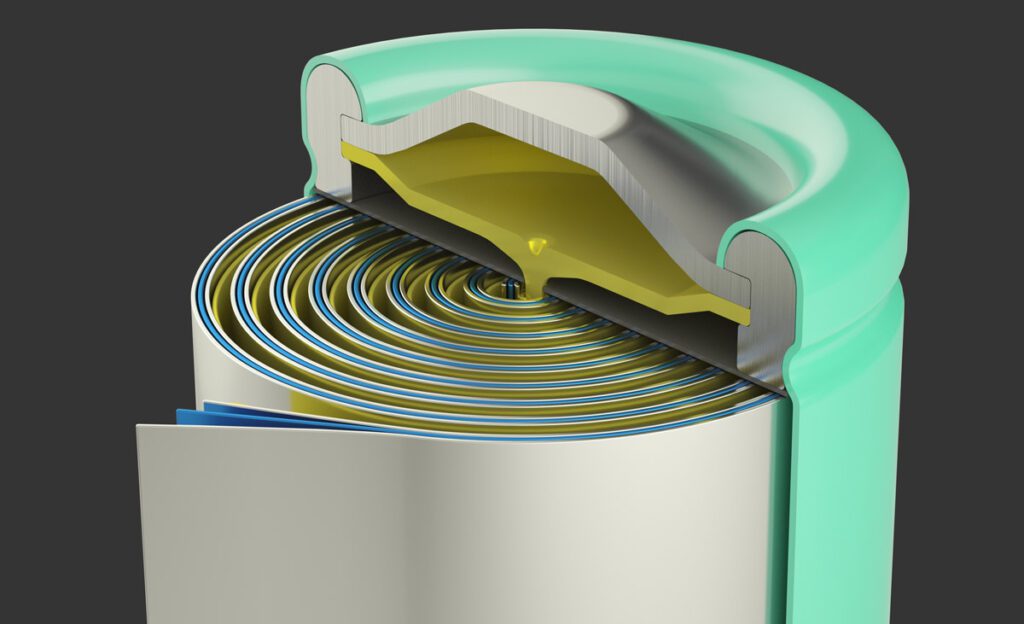

To address the problem, the Stanford researchers developed a plastic material embedded with nanoparticles of graphene-coated nickel with spikes protruding from their surface. Bunched together, the particles conduct electricity. When the battery overheats, the particles separate and current stops flowing. When things cool down, the particles reunite and the battery starts producing electricity again.

“We attached the polyethylene film to one of the battery electrodes so that an electric current could flow through it,” said lead author Zheng Chen. “To conduct electricity, the spiky particles have to physically touch one another. But during thermal expansion, polyethylene stretches. That causes the particles to spread apart, making the film nonconductive so that electricity can no longer flow through the battery.”

“We can even tune the temperature higher or lower depending on how many particles we put in or what type of polymer materials we choose,” said Bao.

“Compared with previous approaches, our design provides a reliable, fast, reversible strategy that can achieve both high battery performance and improved safety,” said Cui.

Source: Stanford University via Green Car Congress