Scare stories about a looming lithium shortage are just that. As informed observers keep pointing out, lithium is not a consumable fuel, it’s easily recycled, and batteries don’t really use all that much of it. Be that as it may, there is a scramble going on to secure supplies of the light white stuff, especially in Nevada, within convenient shipping distance of Tesla’s Gigafactory and BYD’s electric bus plant in Lancaster, California.

The new gold rush comes complete with colorful characters like John Rud, profiled in a recent Bloomberg article. Wildcatter Rud, who holds a master’s degree in geology, goes where the minerals are. “Copper in Canada. Silver in Texas. Gold in Mexico. Iron in Arizona. Uranium in Utah.” His strategy is to find an area with abundant deposits of an element that’s ripe for a price spike, file a claim and wait for the phone to ring. Recently, Rud has been staking claims on tens of thousands of acres in Nevada.

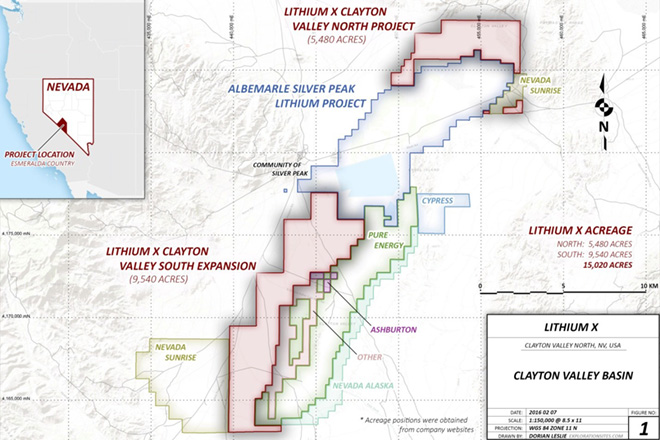

“In my business, you follow the minerals that come in flavor, you might say,” he told Bloomberg. “When uranium prices dropped, I started looking around at what’s going to be hot next. And I thought the batteries for electric cars were just beginning to be nosed around with. We decided on lithium, and where do you find lithium? Well, Clayton Valley was the only place in North America.”

In 2015, just four companies provided 88 percent of the world’s lithium. More recently, at least six startups, including Pure Energy Minerals and Lithium X, have acquired claims in the Clayton Valley area. Industry analysts are predicting that demand for lithium will increase by anywhere from 60 percent to 250 percent over the next few years. Lithium contract prices have increased from $4,000 per metric ton in 2014 to as high as $20,000 today.

In Clayton Valley, lithium is extracted from briny aquifers. Wells are drilled to pump up the brine into gigantic ponds, where the water evaporates in the sun, leaving a concentrated lithium solution. It’s more complicated than panning for gold. “Not everybody can start a plant producing lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide,” says David Klanecky, a Vice President at Albemarle, one of the world’s largest lithium producers and a leading player on the Nevada scene. “There’s a lot of know-how involved in the complexity of the processes – running the chemistry, getting it to concentrate, different specs required by companies we supply to.”

The independent Rud agrees that drilling in Clayton Valley’s soft sediments requires skill and experience. “If you get to a sand layer, it’s easier for the air to go out the side than go up the hole.” That creates a cavern, which can’t support the weight of the drilling rig. “You could tip your rig over,” Rud says. “Total disaster. We have gone through our share of that.”

Source: Bloomberg