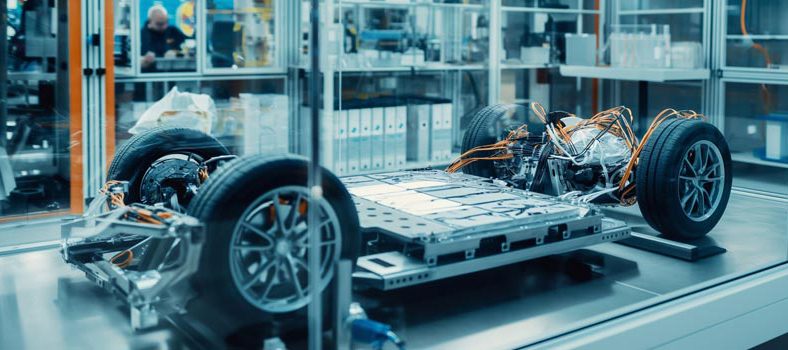

As global demand for EVs increases, many are questioning the adequacy of the existing battery supply chain. A recent article in Transport Dive discusses the challenges involved in building a global supply chain that can keep up with the anticipated growth in EV production.

Elon Musk said in October that a shortage of battery cells is preventing Tesla from ramping production of its Semi. He reiterated that during January’s earnings call, saying that cell supply was “the fundamental limit on electric vehicles right now.”

“We are scaling a supply chain that was capable of supplying the consumer electronics industry to supply the transportation industry,” Celina Mikolajczak, VP of Battery Technology at Panasonic Energy of North America, told Transport Dive. She noted that a phone has one battery cell, and a laptop has a dozen, whereas an EV may require thousands. “How do you quickly scale an industry by 100 times? You need more raw materials, the skilled talent and machines to extract the raw materials, the factories to process the raw materials into cell components, and then the factories to turn those components into cells.”

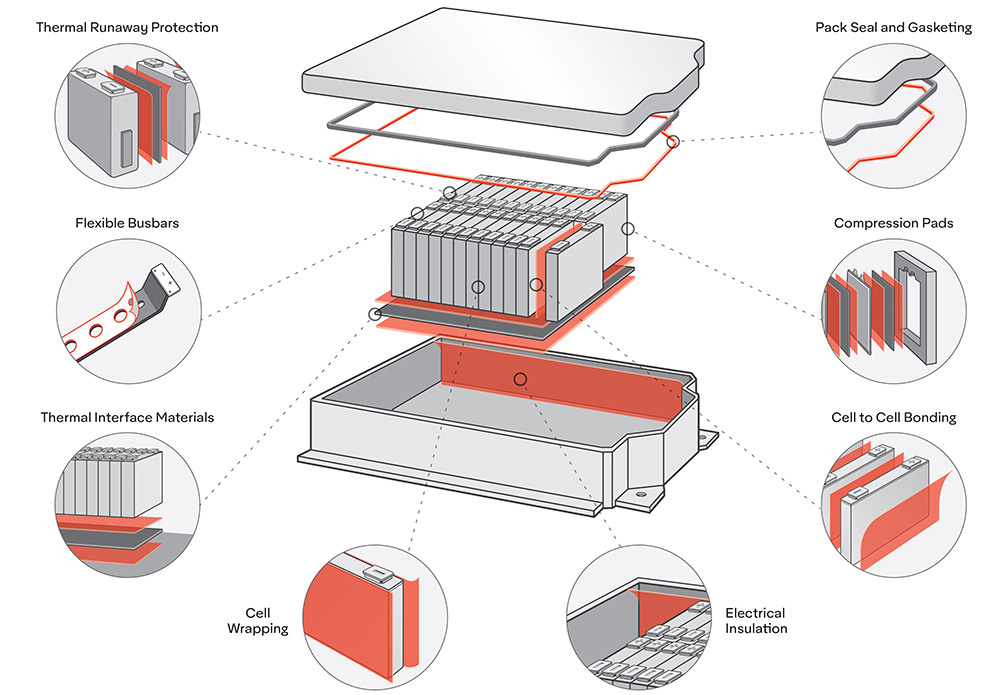

Batteries represent the key component of an EV—about 40% of the value of the vehicle, James Nicholson, a partner with consulting firm EY-Parthenon, told Transport Dive. That’s why vehicle OEMs, including Tesla, GM and Toyota, are increasingly producing cells and packs in-house. “You don’t want that value going elsewhere,” Nicholson said.

Furthermore, the EV battery market is currently dominated by Asian firms. Nicholson says 97% of current EV demand is supplied by battery firms from China, Japan and South Korea. The European Commission recently approved a multi-billion-dollar investment to develop battery production on the Continent, and US policymakers are also taking tentative steps in this direction.

Further upstream, the raw materials for cells, especially lithium, nickel and cobalt, present another set of problems. “There’s plenty of lithium around in the ground. There’s not a physical shortage of it,” Nicholson said. “But there’s an economic shortage of it, which is [that] lithium prices don’t support the mining investment that’s required to get it out of the ground profitably.”

“There are sources of nickel in North America and Finland and Russia and in the Far East and in China, but you also have to refine the nickel, and there’s a limited number of places you can do that,” said Nicholson, adding that most of the refining capacity is in China.

As for cobalt, its unsavory reputation is such that automakers are trying to eliminate it from the equation altogether. “Panasonic has already established the technology to produce cobalt-free batteries, and it is expected to be commercialized within the next two to three years,” Mikolajczak said.

Recycling battery cells is also imperative, not only to avoid the environmental damage of junking them, but also as a source of raw materials. Redwood Materials, the battery recycling venture founded by former Tesla CTO JB Straubel, is a pioneer in this field, and is working to establish a circular supply chain for cells. “The largest lithium mine is in the junk drawers of America,” Straubel recently quipped.

Source: Transport Dive