Researchers in Italy, South Korea, and Scotland have reported designing lithium-air batteries with major advancements in charge and discharge cycles with little capacity loss.

In the race to build a better battery, researchers are testing all kinds of rare elements and high-tech nanomaterials. How ironic would it be if the miracle material turned out to be…air? Several groups are working on lithium-air batteries, which have the potential to deliver far more energy density than the lithium-ion kind. A recent article in IEEE Spectrum discussed some of the latest advances.

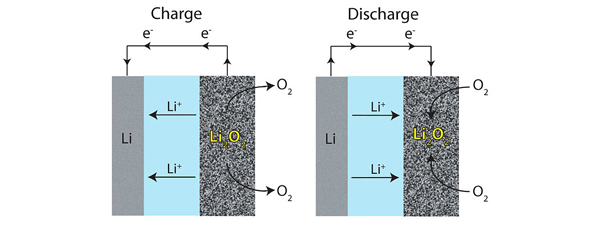

Lithium-air batteries work by exposing a lithium anode to an electrolyte that drives positively charged lithium ions toward a cathode made of a porous material that allows oxygen from the air to form lithium peroxide. Unfortunately, it’s not so easy to reverse the process to create a rechargeable battery. “There’s no electrolyte that currently works well,” explains Stanley Whittingham, an expert in materials science at Binghamton University.

Last month, researchers in Italy and South Korea reported designing a lithium-air battery that overcomes this problem, achieving approximately 100 charge and discharge cycles with little capacity loss. And last week, a research team in Scotland reported in the journal Science that they had achieved 100 cycles with a different lithium-air design.

Some carmakers are exploring lithium-air technology, but most researchers don’t seem to consider it that promising for car batteries. One problem is that in order to provide the same energy density as, say, gasoline, lithium-air batteries require more space – although not much more weight – than the fossil fuel. Professor Whittingham predicts that the technology will be used for large, stationary energy-storage applications rather than for portable batteries. Another problem is that lithium-air batteries are chemically delicate: the lithium gets diverted into dead-end reactions with water or carbon dioxide in the air, so the electrodes may need to be sealed or filtered so that they interact only with dry air and the electrolyte, an added complication.

Source: IEEE Spectrum

Image: Na9234 (wikipedia)