In mid-July, Tesla Motors made a trio of Model S update announcements. The new options included a 70 kWh rear-wheel-drive base model, an upgrade for the high-end battery pack from 85 to 90 kWh (providing about a 6% increase in range), and Ludicrous mode, which offers a 10% improvement in the car’s 0 to 60 mph time, to 2.8 seconds.

The media was most enamored with the extra fraction of a second of acceleration in Model S’s new Ludicrous mode, and they should be. As many outlets pointed out, the new top of the line P90D accelerates from 0 to 60 mph faster than many gas-powered “supercars” that cost more than $1 million from the likes of Ferrari, Lamborghini, Pagani, McLaren, and Porsche. Very few cars are faster than the newest Model S, and none of them are 4-door sedans.

In addition to the awesome engineering achievements that push the power limits to new heights, CEO Elon Musk revealed a bit more about the increase in energy density of the cells in the new 90 kWh pack. During a conference call, Musk told reporters that “it is, actually, as a result of improved cell chemistry. We’re shifting the cell chemistry for the upgraded pack to partially use silicon in the anode. This is just sort of a baby step in the direction of using silicon in the anode. We’re still primarily using synthetic graphite, but over time we’ll be using increasing amounts of silicon in the anode.”

Introducing silicon into automotive-grade lithium-ion cells represents a huge milestone for the EV industry. Silicon is widely considered to be the next big thing in anode technology, because it has a theoretical charge capacity ten times higher than that of typical graphite anodes. “It’s a race among the battery makers to get more and more silicon in,” Jeff Dahn, the prominent battery researcher who will begin an exclusive partnership with Tesla in June 2016, recently told Fortune.

However, further advances in silicon anode technology will not come easily.

![]()

Silicon versus graphite

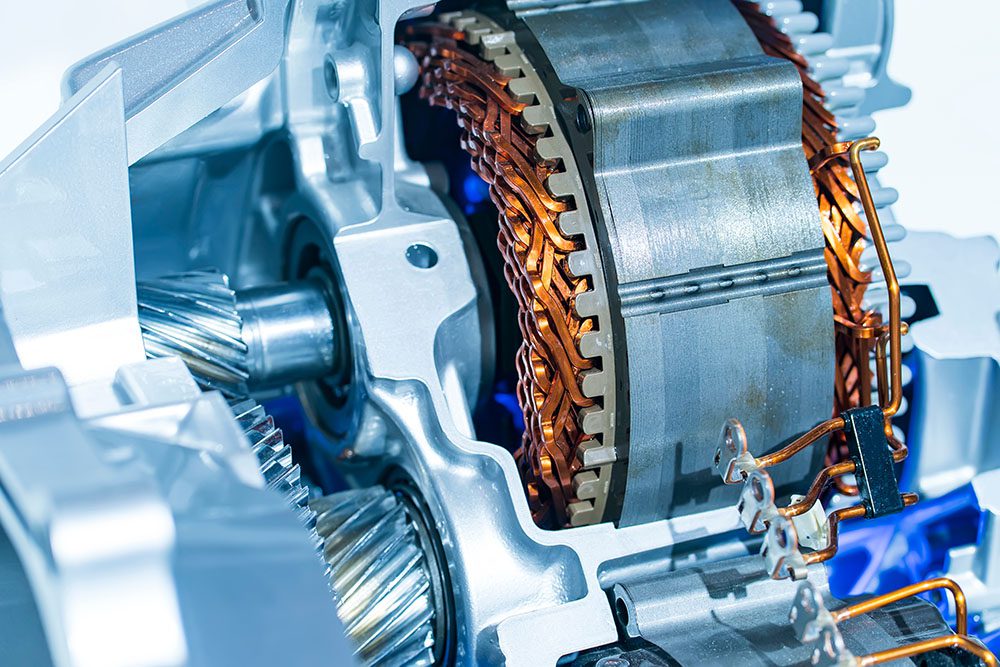

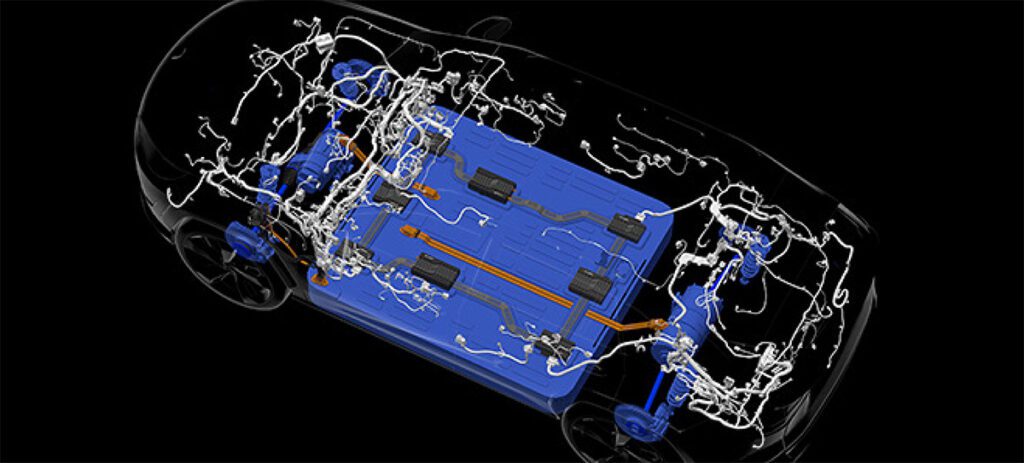

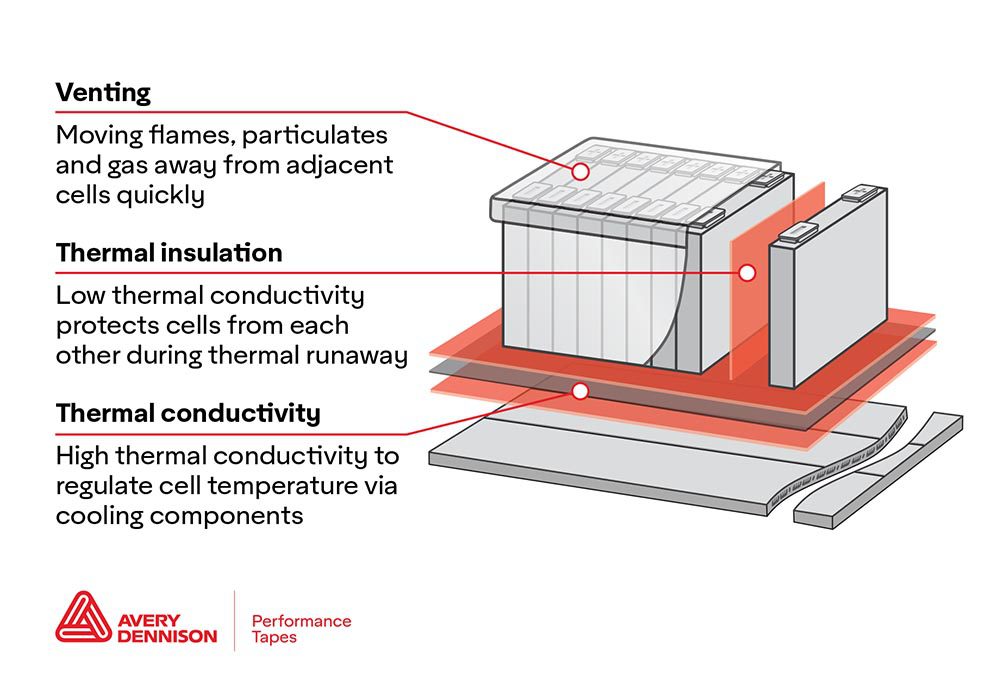

Replacing the graphite in a cell with silicon means that you can use less anode material and fill up that extra space with more cathode material – effectively increasing the overall energy that is contained within the same volume. This is due to a fundamental difference in the way that silicon “stores” lithium.

The layered graphite structure absorbs the lithium ions through a process called intercalation. It is essentially sheets of graphene where lithium ions can be stored between the layers.

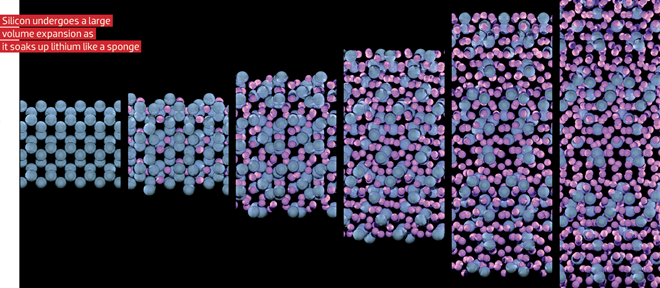

Silicon, on the other hand, can absorb more lithium ions, because the two materials form an alloy with a theoretical specific capacity much higher than that of graphite.

Image by Rees Rankin, courtesy of Argonne National Laboratory (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Silicon’s challenges, however, arise from the same attributes that make it attractive. Unlike the porous graphite material that has specific sites open and waiting for ions, when the lithium-silicon alloy forms, the structure of the anode changes, resulting in large volumetric fluctuations. For example, if a particle of silicon absorbs as much lithium as thermodynamically possible, its volume increases by about 300%. That compares to about 7% expansion observed in the intercalation of lithium into graphite.

The problem with the current state of silicon anodes is that the repeated expansion and contraction during charging and discharging leads to drastically reduced cycle life.

Failure mechanisms

To get a better idea of the challenges of silicon and what researchers are doing to overcome them, Charged talked to our go-to battery R&D experts at Wildcat Discovery Technologies.

Dee Strand, Chief Scientific Officer at Wildcat, explained that when you add a lot of silicon to anodes there are two big failure mechanisms: problems with the electrode itself and with the solid electrolyte interface (SEI) layer.

“The electrode is a whole bunch of particles glued together,” said Strand. “When you have particles that change dimensions so dramatically with every cycle, they tend to fall apart. The particles themselves pulverize. They crack. The glue comes undone. And your cycle life is very short.”

The SEI layer is what enables the battery to operate in an efficient and reversible manner. It’s a film composed of electrolyte reduction products that start forming on the surface of the anode during the initial battery charge. It functions as an ionic conductor that enables lithium to migrate through the film during charging and discharging. Under typical operating conditions, it also serves as an electronic insulator that prevents further electrolyte reduction on the anode.

“With silicon anodes, a nice passivation layer is formed on the particles,” explained Strand. “But as the silicon expands and contracts, it essentially cracks apart that layer and then makes more. Over time it ends up with a very thick resistive film on the anode, which causes it to lose both capacity and power. So that’s the other mechanism that causes the cell to fade very fast.”

Little by little

So how have Tesla and others been able to add silicon to cells that are now commercially available?

Strand explains that, to date, the only way battery developers have been able to achieve long cycle life is not to use very much silicon. The porosity within the graphite matrix provides room for a small amount of silicon particles to expand and contract without disrupting things too much. “When you start using more and more silicon, it’s much harder to keep that electrode and SEI layer bonded together,” said Strand.

The cells that contain silicon today – including those used in consumer electronics that have been on the market for a few years – contain such a small amount that it’s not really changing the equation. It’s a small percentage of the anode material, and the majority of capacity is still coming from the graphite. However, battery-makers clearly intend to find ways to overcome the challenges, and add more silicon. As Musk said in July’s announcement, Tesla “expects to increase pack capacity by roughly 5% per year” (although not all of those increases will be solely due to adding more silicon).

According to Strand, making incremental additions to the amount of silicon will “require better binders that hold the electrode material together, and better electrolytes that form more mechanically robust SEI layers on those particles.” The good news is that there are a lot of potential fixes for both failure mechanisms – it’s just a matter of tweaking, testing and repeating, until formulations are found that work well together (a process that Wildcat is particularly good at).

Better materials

One solution to the SEI layer problem might be found in a DOE-funded project that Wildcat has underway to develop better electrolytes and additives for silicon anodes. Wildcat says the project, named EM4, has been very successful at making more mechanically and electrochemically robust SEI layers on the anode. So as volume changes occur, the SEI layer doesn’t crack.

“The electrolyte formulations that are used in today’s batteries are fairly complex, with a lot of different solvents, salts, and additives,” explained Strand. “Using silicon anodes introduces another level of complexity because we’re applying a new constraint – that is, the ability to expand and contract with the silicon. But that’s really where the power of Wildcat’s high-throughput R&D processes shines, and in less than two years we’ve been able to develop fundamentally different electrolytes that don’t have the typical solvents in them.”

Most electrolyte formulations today contain ethylene carbonate (EC) – a cyclic carbonate molecule – and a linear carbonate molecule blended together. One helps solubilize the salt and one reduces the viscosity and makes sure that you have high enough conductivity. Strand explained that with silicon anodes, people tend to add a lot of fluorinated ethylene carbonate (FEC), because it appears to make a more stable SEI layer than EC. However, it’s still that not great, and you have to put in fairly high levels of FEC, around 10-30%.

So, Wildcat decided to develop a new class of electrolytes that contain no EC, and only a small amount of FEC – around 2%. “That really opens up the door to a lot of different chemistries that you can consider to make that SEI layer more mechanically robust,” said Strand. “We now have non-carbonate formulations that give us 300 cycles to 80% capacity, and perform equivalently, or better, to carbonate-based solvents. Because of our ability to look at many different chemistry families and many different combinations, we will continue to make further improvements upon those 300 cycles. There are lots and lots of additives that we currently have in an optimization phase that look very promising.”

The other piece of the puzzle

Even with the perfectly formulated electrolyte for silicon, there is still the problem of the electrode falling apart. Although Wildcat has lots of experience developing new complex electrode materials, it’s not currently working specifically on silicon anodes. But rest assured, many others are.

For example, last year the DOE launched six applied battery research projects as part of its Vehicle Technologies portfolio – all using some form of silicon-based material for the anode. That included teams led by the Argonne National Laboratory, TAIX, 3M, Envia, Penn State/University of Texas at Austin, and Farasis Energy. Charged has also previously covered a variety of private companies working away to solve silicon’s problems, including CALEB Technology, CalBattery, Amprius, EnerG2, and others.

As Strand explained to us, preventing a silicon anode from pulverization during cycling is just as complex a development problem as finding a stable electrolyte, because, again, there are so many variables. “For example, many people are developing nanoparticles because they can manage the mechanical stresses and they don’t crack,” she continued, “but with those high surface-area materials, it’s much harder to find binders that will effectively hold everything together. That issue is also intertwined with the electrolyte because now you need to worry about making a robust SEI layer on a high-surface-area anode material.”

In spite of the complex challenges, the sheer number of groups working to solve the problem is very promising. The market for advanced battery technology continues to grow rapidly as prices drop and energy density increases. Unlocking the potential of silicon could give a company the edge needed to become an early leader in the gigantic new industry. So it’s no surprise that, as Jeff Dahn told Fortune, “the number of researchers around the world working on silicon for lithium-ion cells is mind-boggling.”

SEE ALSO: A closer look at how batteries fail

Read more EV Tech Explained articles.

This article originally appeared in Charged Issue 20 – July/August 2015. Subscribe now!