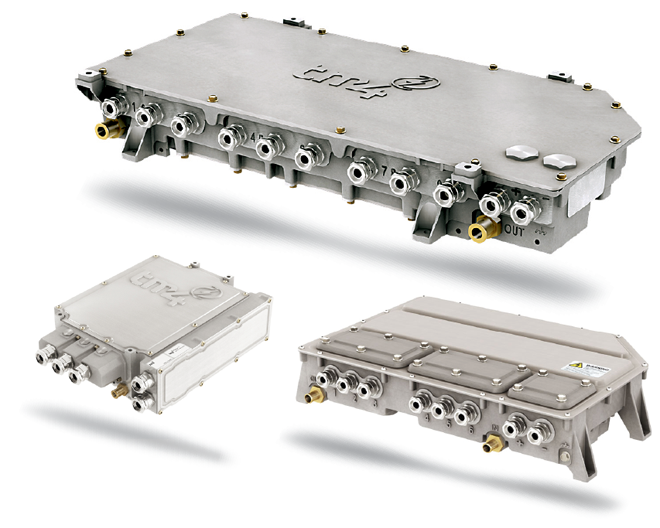

TM4 designs electric powertrains for the most demanding vehicle platforms and duty cycles on the road. Formed as a subsidiary of the public utility Hydro-Québec, the company sells its motor and control products to manufacturers of heavy-duty trucks and buses around the world.

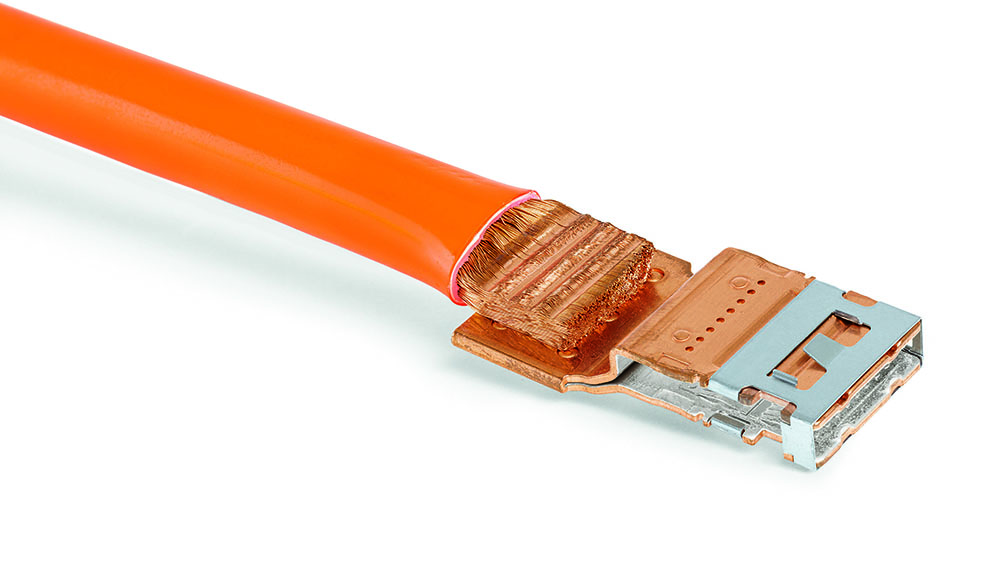

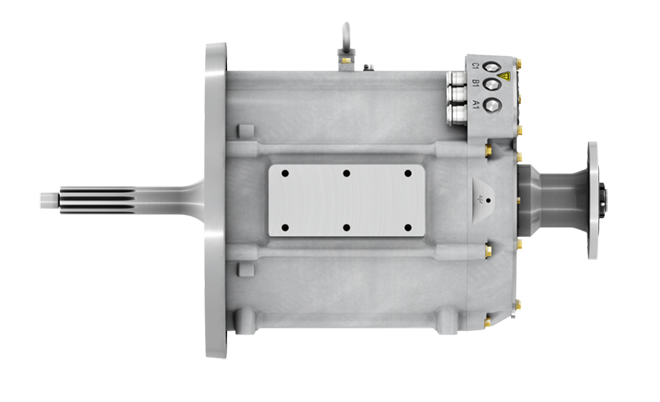

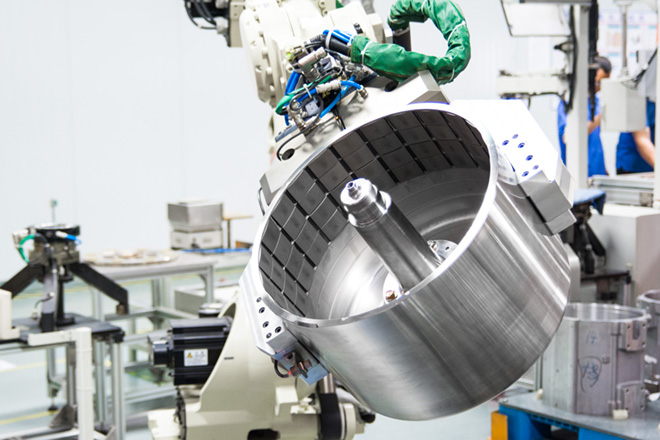

In June, TM4 will release an update to its SUMO product line that now powers thousands of electric buses and trucks. The current technology found inside TM4’s electric motors is based on surface-mounted permanent magnets and outer rotor topology. The updated systems will widen torque and speed operating ranges and decrease the use of rare-earth magnets by 25% using reluctance-assisted technology.

Electric motor torque is produced by the interaction of a moving magnetic field (created electrically) and a fixed magnetic field (either from permanent magnets or an electromagnet). In a reluctance-assisted machine, some of the torque is also produced from the interaction between a magnetic field and a magnetic material (steel).

Charged recently chatted with TM4’s Olivier Bernatchez to learn more about the company’s new motor technology, direct-drive powertrains, in-wheel motors and more.

Charged: How will these new powertrain options fit into your existing product line?

Olivier Bernatchez: Our highest power/torque products are what we call the SUMO HD family, and they’re typically for the largest vehicles – buses that are about 12 meters long or longer (and trucks of a similar weight class). Below that, we have the SUMO MD family which is targeted for buses around 9 or 10 meters (or larger buses that only operate on flat roads or at lower top speeds).

This new technology will be implemented into the SUMO MD family with three new motor options. So, without changing the dimensions of the motor, the new rotor technology will increase performance (torque and speed) by about 40-45%. With reluctance-assisted technology, we’ve managed to improve the performance of the MD family so we’re basically getting more out of the smaller package. Soon we’ll start to implement this technology in our other products as well.

A lot of motor designs are now being driven by the desire to limit the use of rare-earth magnets, due to their high price and volatility. We’ve been able to decrease the amount of rare-earths used in the fabrication of our motors by 25% while increasing torque and speed capabilities. And it’s also safer technology. Reluctance-assisted machines lead to easier field weakening and lower short-circuit current. This means safer fault conditions, as any type of short-circuit generates a very low torque.

Charged: All of TM4’s traction motors use an external rotor design, which is relatively uncommon for production vehicles. What drove the decision to go with that technology?

Bernatchez: We started with external rotor technology because in the 1980s, our initial research work was with in-wheel motors. External rotor motors generate the highest amount of torque with the smallest amount of material.

Initially, we had smaller machines and we were targeting the passenger vehicle market. Over the years we switched our focus to fleet vehicles – buses and trucks – because we saw a huge opportunity in serving this market, especially with the strong incentives in China. Because high torque is in line with what commercial trucks and buses need, we kept the external rotor topology and scaled it up for buses and trucks. While we still have products for passenger cars, the area where we’ve seen the biggest growth is definitely in commercial vehicles.

Having the external rotor helps us to maximize torque, because we can maximize the diameter of the air gap between the rotor and stator. Torque is proportional to the square of the air gap diameter.

We think that direct drive to the differential is a great option for the bus and truck market because it’s the best compromise of packaging constraints, efficiency needs and low maintenance. Without a gearbox, you end up with a bigger motor, but you ultimately save on space, costs and driveline losses. Gearboxes can be expensive in the commercial market, and they have mechanical losses of about 5-10%. For an all-electric bus with 200 or 300 kWh battery packs, 10% in losses is a lot of money.

So, the main rotor technology found inside TM4’s electric motors to date was based on surface-mounted outer rotor topology in which the magnets were installed directly to a rigid carbon steel rotor. Our new technology is still external rotor designs, but we’re moving away from fully surface-magnet-based and replacing some of the magnets with soft magnetic composites.

Charged: TM4 also designs and builds its own line of power electronics. Why not partner with an inverter company, as many other motor manufacturers do?

Bernatchez: We’ve been designing and producing power electronics since the beginning. We think it’s a major advantage for our customers, because it’s always better if you can find both motor and controls from the same supplier for best performance, but also for support and warranty issues. Also, we think that to design and build great power electronics, it is important to really understand motors. When you design your own, it comes more naturally. So as we increase the offerings for the motors, we’re also in the process of optimizing and refining our inverters for cost-effectiveness.

We’ve found that – especially in the bus market – OEMs want to source as many components from us as possible, so this led us to also develop auxiliary power supply products. It was not initially part of our product line, because we were mostly focused on traction inverters, but from a technology point of view the hardware is very similar. So it’s just a matter of developing software that’s optimized for a different type of application.

In the past, the demands from the electronic systems in the bus were much lower. As more and more components were electrified, our customers needed more auxiliary power, and we started getting a lot of requests for power supplies. So now we offer some quite powerful auxiliary inverters.

Charged: It seems that the electric bus market has a lot of momentum around the world as it moves from the demonstration-project phase to actually replacing diesel fleets. Do you agree?

Bernatchez: Absolutely. The electric and hybrid bus market in Europe and North America is steadily growing, but is still small compared to China, where government policies are very encouraging of the technology. The regulations encourage OEMs and cities to go electric in volumes that are really high. So we see really big orders coming from China.

We are based in Canada, but we now have a joint venture plant in China that we established in 2012. Currently, we are selling motors in the thousands per year.

Charged: In the past few years, we’ve heard a lot about the potential benefits of in-wheel motor technology, and TM4 continues to make announcements about new in-wheel research projects. However, the automotive market has yet to adopt them in production vehicles. What are the biggest challenges to adoption?

Bernatchez: Cost is definitely a challenge. A lot of the in-wheel motors have power electronics and motors inside the same enclosure. This makes for a convenient but technologically challenging package. I think the prices for that type of module will go down, but it’s very likely that two wheel motors will always cost more than one single drive motor used in a central location with a differential. This is because the motors need to be bigger in order to produce the torque that you need at the wheels, so they’re not going to get a lot smaller than the wheel itself, and if they do they’ll use some gears and it becomes even more complex, which also makes you lose some of the efficiency advantages that made in-wheel motors interesting in the first place.

We also see that the OEMs have a lot of issues getting these vehicles validated and into production for many different reasons. You need to really redesign the vehicle based on the new weight balance. The unsprung weight is a challenge. There are a few companies that have proven that it can really be minimized, but everything that you use to minimize it is still quite expensive. For now, I’d say cost is the main challenge for the technology. It could change in the longer run.

There are some companies offering in-wheel motors for buses. From a maintenance point of view, especially for the wheel size of a bus, it’s very challenging because you have a wheel that now weighs hundreds of kilograms more than a traditional one. If you have a minor problem with your wheel, then basically your motor is not functional. That’s an expensive problem, even if the problem itself is minor. Think about a simple flat tire event and how complex it now becomes.

I think there could be two different types of markets that drive the adoption of in-wheel motors. There are smaller vehicles where packaging space is highly valued – in fact in-wheel motors are already in use in things like scooters and low-speed vehicles. Then there are very big industrial vehicles where packaging is also at a premium and where added weight at the wheel means better traction. We’ve seen some big mining trucks that are very heavy and need one motor per wheel, and if you don’t use an in-wheel motor, then you need gears, and you need to mount the motor in a way that takes some space under the vehicle. Again, it’s always a matter of tradeoffs between having the perfect packaging and price. For them in-wheel motors make sense, but of course they need to be very big and very expensive. It’s really a niche type of product.

We continue to do development. As part of a recent grant we received, we developed a new type of in-wheel motor that we are testing with an OEM partner – just in the prototyping phase. Even if this work doesn’t end up in production, we still will bring some of the new optimization and technologies into our existing motor and power electronics lines. Just like it was for us when we started as a company, the research done on in-wheel motors helps innovate, because you need to work with very tight packaging constraints and you need to develop some technologies that make the motor more robust.

This article originally appeared in Charged Issue 25 – May/June 2016. Subscribe now.