The Biden administration has announced three major pro-EV initiatives in recent months—a revamping of the federal tax credits, an infrastructure funding package, and new EPA emissions standards. However, government programs are always complex, and they tend to undergo major revisions between the proposal and policy stages. To help us sort out how the new policies are likely to unfold, we turned to Margo Oge, former Director of the EPA’s Office of Transportation and Air Quality and author of the book Driving the Future.

Charged: Last May, as the EPA was in the process of developing the new emissions standards, you gave us a helpful explanation of the way the system works. Now I understand the new rules are finalized. Are you pleased with the way they came out?

Margo Oge: Yes, absolutely. Basically, they finalized [rules for model years] 2023 through 2026. For 2026, what they did that I think is very important—and it’s better than the proposal—was to increase the required number of zero-emission vehicles by 2026. I believe the proposal was about 8%, and the final is 17%. By 2026, car manufacturers will have to [make approximately 17% of new vehicles] in their total fleets electric and zero-emission.

To me, that is important for three reasons. First of all, President Biden has made a commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% in 2030 from the 2005 level. Transportation will be, probably along with the energy sector, the key sector that will require to be addressed in order to achieve that goal.

By 2026, car manufacturers will have to make approximately 17% of new vehicles in their total fleets electric and zero-emission.

When the proposal came out—I believe it was last August—he also announced an executive order to federal agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Highway Safety Administration (NHTSA), to set a set of standards starting in 2027 through 2030, and by 2030 about 50% of new cars sold in the US have to be zero-emission. I think having a regulatory requirement for 2026 around 17% will help the car companies to make that jump to 2030. That’s the second reason.

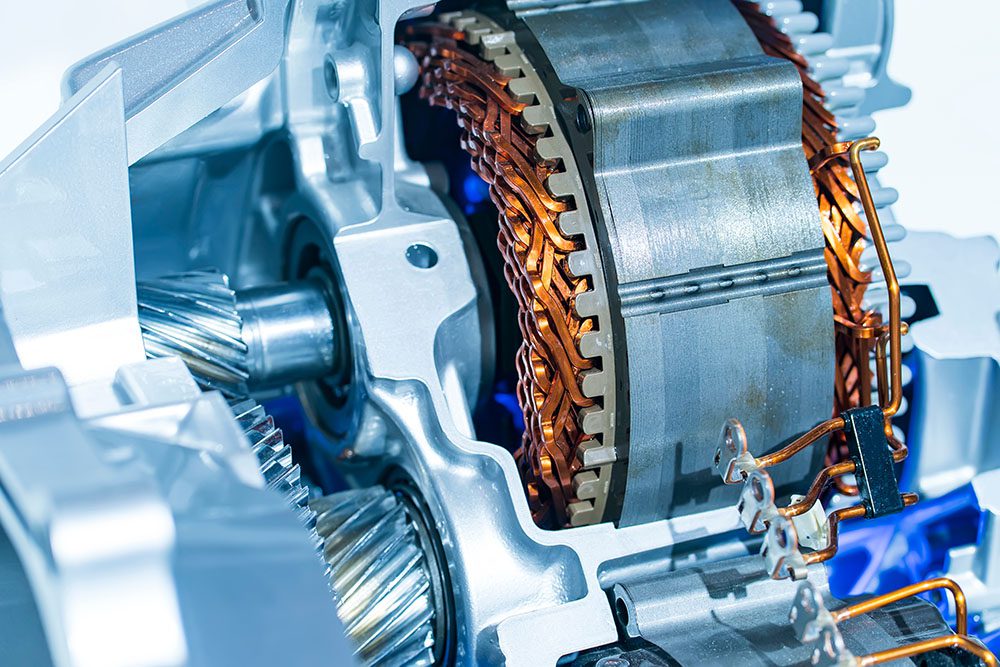

The third reason is that the car companies are making all kinds of commitments. We’re seeing over $350 billion globally put forward from now to 2030 on electrification. Every car company is making huge investments. The last company to make those investments that was dragging their feet is Toyota. They just announced about $35 billion [in investment] by the middle of this decade. GM has made a commitment to 100% zero-emission vehicles by 2035, the same with Ford.

The companies are investing. The market is rewarding those investments. For me, the most important thing is that there is an urgency across the planet to address climate change. Transportation is a key segment of the economy that contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. We cannot get there without clean transportation.

But to answer your question, yes, I’m very pleased with the final standards.

Charged: I understand that the EPA sets emissions standards, and NHTSA sets fuel economy standards. To be clear, what they just finalized was the EPA emissions standards, right?

Margo Oge: Right. But NHTSA is going to finalize [its standards] in the next month or so. We have to understand that NHTSA’s final action will affect 2024 through 2026, whereas the EPA’s final action affects 2023 through 2026.

The reason that NHTSA cannot mandate that car companies meet a new standard in 2023, is that they need to give 18 months lead time before implementation. As you know, many companies, for the year 2022, most of these decisions have already been made and cars have been certified in 2021. That’s the difference. That’s why we didn’t see a NHTSA final action yet. The final action would not affect 2023. It would be 2024.

Charged: But it’s all kind of a package, right? The EPA and NHTSA standards are interrelated.

Margo Oge: It’s a package, that’s how I would look at it. It will be very consistent, in my expectation, with what the EPA announced for 2023 through 2026. I strongly believe that NHTSA will be very comparable for those years as well.

Charged: Would it be fair to say that the car companies are already designing their cars to comply with this new standard? They’ve known this was on the way.

Margo Oge: Yes, absolutely. And also, let’s not forget that the car companies are not designing cars [only] for the US market. They’re designing cars for the global market, most of them. GM and Ford have big roles in China, in Europe. These are global companies, and Europeans are moving forward with even more stringent standards. They have proposed 55% new car sales to be electric in 2030, and 100% by 2035.

It provides a level playing field. If the CEO of a car company leaves today and the board changes, those commitments can go away. You need the companies to be able to go to their boards and say, “We have to continue to invest because this is what is required.”

The car companies are preparing, are investing, are making commitments, but having the regulations in place [is important] in my mind. Somebody has said, “Well, if the car companies are doing this, why should the government have any role?” I think it’s one thing to have a commitment for 2030 and 2035, and it’s another thing to have to meet legal requirements and standards. It provides a level playing field. If the CEO of a car company leaves today and the board changes, those commitments can go away. You need the companies to be able to go to their boards and say, “We have to continue to invest because this is what is required.” We saw that happening in Europe in 2021, when the European market for EVs became second [only] to China, because they had a strong CO2 standard for 2021. The car companies had to meet that standard.

Charged: They’re already designing cars to meet the more stringent European standards, so it’s not going to be any challenge for them to meet the new US standards.

Margo Oge: Exactly.

Charged: As we discussed last time, the Trump administration tried to water down the federal regulations. They had four years to do that, but the clock ran out on them. I find it interesting that Biden’s EPA was able to finalize these new regulations in about a year.

Margo Oge: The Trump administration did finalize the standards in 2020, [but] they got legal challenges. The environmental groups, the states, California challenged them. It has been on hold. The Biden administration walked in and they said, “We don’t want to go to court and challenge those standards.” The courts put them on hold, all these legal challenges.

In my view, the Biden administration was able to propose and finalize the standard in a 12-month timeframe for two reasons: the first and most important is that the agency evaluated what California had done with the six car companies. If you remember, six car companies joined California—they cut a deal to have standards that would be more stringent than what the Trump administration was proposing, but somewhat less stringent than what Obama had put in place. That program was already in place, and there was broad support by six major companies. That’s one issue.

The second issue is that the EPA had done all the analysis, what it would take for the 2025 and 2026 timeframe, where the companies were and where the science was. The Trump people, they were designing a program based on fiction, not science, they had to make up stuff. As you know, there was not this analysis that they were putting in place. They were legally very vulnerable. Let’s assume that the Trump administration [had won in] last November’s elections—they would have had very big challenges in court. They could not [have sustained] what they finalized.

I think Biden’s EPA benefited from the California work and also benefited [from the fact] that they had done all the analysis even during the Trump administration, and were pushing the Trump White House where the science should lead these types of standards.

Charged: Do you think the new standards will also face legal challenges?

Margo Oge: I very much doubt it. The reason I say that is that I don’t see any of the car companies challenging them. Potentially, there could be a challenge by somebody in the dealers’ associations, but I think it will be very hard to show harm. I’m not a legal expert, but I’ve been around lawyers for a very long time. If you challenge the standards, you have to show that there is harm, and I don’t see that a dealer can do that. I very much doubt it would be challenged. If they get challenged…I don’t see any reason that there will be a victory from the other side. I think you’re going to get a number of car companies [to support] the Biden administration to keep those standards in place.

Charged: The car companies don’t have any real motivation to challenge the standards, do they, because they’re going to easily meet them.

Margo Oge: Exactly.

Charged: The political media is predicting that, unless some sort of a miracle happens, the Republicans are going to retake control of the House in November, and I’m sure they’ll be very interested in undoing or watering down these regulations. Will there be anything they can do to turn the clock back?

Margo Oge: No, absolutely not. Congress has, I think, 90 days or 160 days to act. Usually, Congress acts because there is a lot of private-sector interest. The Republicans would act because the car companies don’t like the standards. By November, the congressional authority [will have] gone away.

The only way in which the November election could impact the EPA would be for the next set of standards, for 2027 to 2030.

The only [way in which the] November election could impact the EPA would be for the next set of standards. As I mentioned last time, when the EPA proposed the 2023-2026 greenhouse gas standards, the White House also put out an executive order directing the EPA to start working on the next set of standards, for 2027 to 2030. I think the deadline that they gave the agency is July of 2024. I could see that standard, depending on what’s going to be finalized and where the car companies are going to be, potentially being challenged by a new Congress.

Charged: Well, we all hope that by that time, the transition to electric will be pretty much accepted, and there won’t be any real motivation to attack the standards.

Margo Oge: Yeah, I absolutely agree with you. I do hope that the financial incentives in this Build Back Better legislation will happen, because there are over $500 billion of climate change [investments], from renewable energy to incentives for electric vehicles. I hope that passes, because I think that will be an important element, especially for the 2030 requirements for 50% of vehicles to be electric in the marketplace.

Charged: Do you think the Build Back Better bill, which includes the reform of the federal tax credits, still has a chance? The last I heard, it sounded like it was pretty much dead.

Margo Oge: Well, I hope that’s not the case. There are a lot of important elements in this legislation, and climate change is one of the big elements. There is an opportunity to break this bill into smaller pieces where the climate change provisions could survive.

Charged: So, some elements of it are likely to survive?

Margo Oge: That’s what I’m hearing.

Charged: There’s a third federal initiative on the table: the infrastructure bill, which is part of what they’re now calling the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. This sounds great—$7.5 billion for infrastructure—but it seems very vague at this point. Can you give us an idea of how that’s likely to be structured and how long it’s going to take before we hear more details?

Margo Oge: The good news is that the Secretary of Energy and the Secretary of Transportation are responsible for implementing this bill, and they already have formed a new group [the EV Charging Action Plan] to implement this piece of legislation. They’re going to come up with criteria, but states are going to have a big [part to play].

I expect, based on what I’m reading, a pretty fast movement of those resources. The main reason I’m saying that is because there is huge expertise in these two departments, both the Department of Energy and the Department of Transportation. I have a lot of respect for both of those secretaries. I expect the money to get out very fast.

Charged: It’s going to go through the states, but does that mean that every one of the 50 states is going to get a pot of money, or will there be something like a competitive RFP process?

Margo Oge: I don’t know, but I would be very shocked if every state doesn’t get resources. The question is more, what type of criteria they’re going to use to allocate those resources—population versus air pollution versus rural communities. Some states like Montana, for example, it’s less populous, but a big state, so how do you put that infrastructure in place? My hope and expectation is that there will be a set of proposals, [and the public can comment] before they finalize their plans.

Charged: How long before we see that detailed proposal?

Margo Oge: I don’t know. I have no inside information, but my hope is that they move very, very fast because we have zero time to waste here. And you have the car companies that have been thinking about it, from Tesla to Volkswagen to GM. You have states like California that have expertise. There is a lot of expertise right now that can help the administration to move these resources very fast.

Charged: Private companies are going to be implementing most of this, right?

Margo Oge: Yes. I would suspect so.

Charged: I just wrote an article in which I argued that, of the three big federal EV initiatives—the Build Back Better Act, the Infrastructure Bill and the new EPA regulations—the EPA regs are the most important, because they take effect right away, and because, as you said, it’s something that’s going to be difficult for the anti-EV crowd to undo.

Margo Oge: I would say that the first installment of the EPA standards is the most important, but it will not be the most important if they don’t implement the executive order and put [the next set of standards] in place from 2027 to 2030, that mandate that 50% of all new car sales in the US are EVs. If the only thing we see from the EPA is the first installment and not the second, a strong second installment, that will be the biggest disappointment for me.

Charged: Because as you said, the first installment is really just putting us back to where we were.

Margo Oge: Exactly, with a little bit more ambitious program for 2026, because the Obama program ended in 2025. What Biden’s EPA did was to increase the [requirement] for EVs for 2026. By itself though, it’s not significant if they don’t successfully implement at least 50% for 2030. I personally believe that there should be 60% EVs in 2030, because a recent study by the International Energy Agency [found] that we need 60% EVs globally by 2030.

To answer your question, it will be the most important if they’re successful with the second installment as well.