Battery “gigafactories” are under construction all over the world—and none too soon. As EV sales grow, it is critical to establish local battery production and shorten supply chains. However, state-of-the-art cell packaging and chemistries are evolving quickly these days. How will cell manufacturers future-proof their cell production facilities? How flexible will these new plants be to modify formats and chemistries? These are a couple of the questions Charged asked Britishvolt’s Richard LeCain, Director of Cell and Process Engineering, and Ben Kilbey, Director of Communications and Media.

Britishvolt’s goal is to create domestic battery production all around the world, and the company is currently building its first cell factory in the UK. The site in the Northeast of England was selected because of the abundance of renewable energy—it has access to the North Sea Interconnector, so the company can take hydropower-created electricity from Norway and feed wind power back.

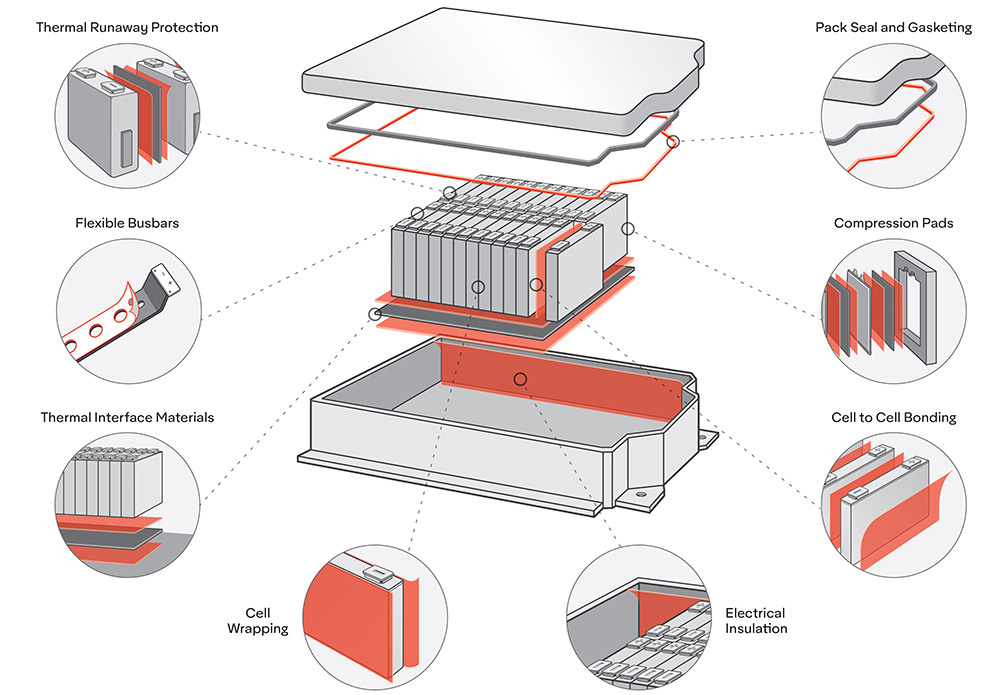

The company recently signed agreements with UK auto manufacturers Lotus and Aston Martin to develop cell technologies designed specifically to support the two brands’ electrification roadmaps. For Aston Martin, a joint R&D team will design, develop, and industrialize battery packs, including bespoke modules and a battery management system.

Britishvolt is also currently looking at sites in the Canadian province of Quebec for its second factory, where it also plans to “create domestic IP.”

Charged: What stage of development are you at right now, and what are the next steps to get to production?

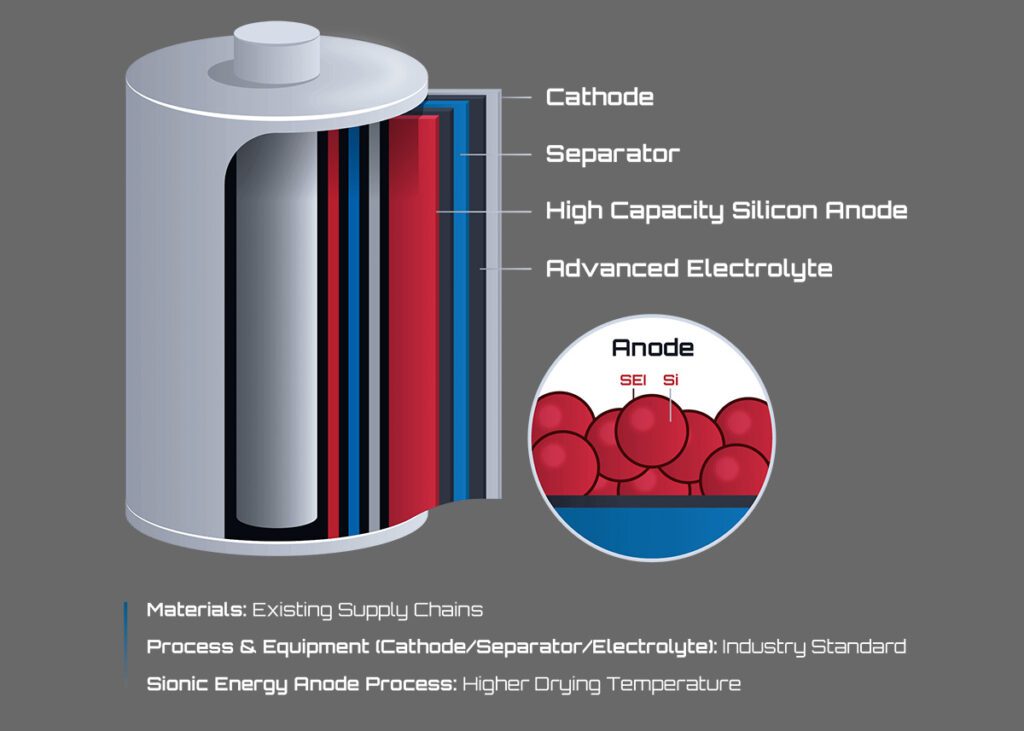

Richard LeCain: Britishvolt is in the early stage of development and scale-up. We’re trying to address the EV market’s challenges, so we are selecting materials and chemistries that align with specific market requirements. We know who we’re trying to reach, and we cascade that understanding into material selection, supplier development, and cell design, to satisfy an array of customers throughout the EV sector.

One year ago we weren’t making any cells, but by the end of 2021, we were going through campaigns to build thousands of cells.

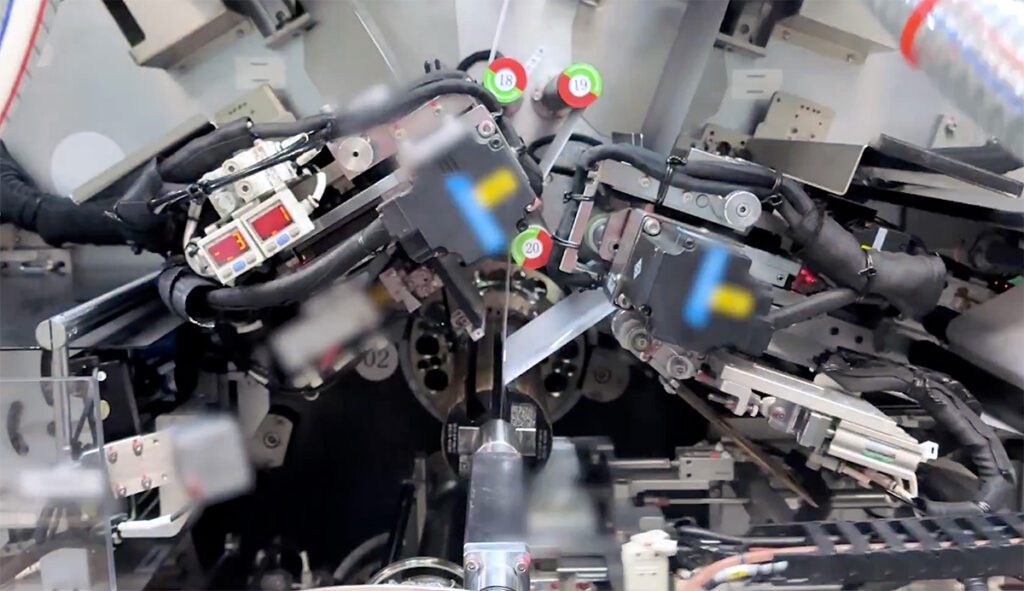

Right now, I’m sitting in Coventry at an organization called UKBIC [UK Battery Industrialisation Centre], who we’ve partnered with to execute that scale-up work. One year ago we weren’t making any cells, but by the end of 2021, we were going through campaigns to build thousands of cells.

Ben Kilbey: Britishvolt was founded in 2019 by our CEO Orral Nadjari. When I joined in 2021 we had around 20 employees. Now, we number nearly 200, so we’re growing very quickly. We received government backing at the beginning of 2022, and we announced our first successful A-samples coming out of the UKBIC facility.

One of the reasons we came to the UK is the incredible ecosystem of academic research and development facilities. We will progress to making our own scale-up and R&D facilities, but having them already established here in the UK has allowed us to hit the ground sprinting and is propelling us forward.

Richard LeCain: My group develops cells from early-stage prototypes with the goal of transferring those designs into production. We work on designs that are destined for the gigaplant in Northumberland.

Prior to Britishvolt, I spent 17 years at A123 systems in the US, where I led a group that was focused on developing LFP cells.

Charged: Has that process changed significantly since you started doing it at A123, or is it basically the same?

Richard LeCain: There are always new chemistries, new advances and new claims. And it’s up to us to verify those claims and make sure those chemistries work in our cells.

Leveraging some of the work that’s been done on the modeling and simulation side is an area in which Britishvolt is trying to lead. We’re working with places like Imperial College London, where they’re using modeling and simulation tools to better predict performance of cells with new materials. That’s how we are trying to improve cell development cycle times, by making it less iterative. We hope to be able to cut down on the number of experiments and the amount of work that we’ll perform on new materials, which will speed up our development process.

Charged: Is the bottleneck for development still the huge number of cycles you have to do to get the right amount of data to have an idea of where you’re headed?

Richard LeCain: It can take three months to gather enough data to get a good sense of how your chemistry performs. You can perform accelerated life testing of cells to try and get a look at early failures, but it still takes time to cycle the cells properly and get a real-world look at how they’re going to perform.

It can take three months to gather enough data to get a good sense of how your chemistry performs. You can perform accelerated life testing of cells to try and get a look at early failures but it still takes time to cycle the cells properly.

Charged: A battery manufacturing equipment supplier recently told us that it estimates there are somewhere north of 100 cell gigafactories in the world being built. That must be a huge demand on the suppliers. Do you see your suppliers being pulled in different directions?

Richard LeCain: We’ve seen some constraints in the field around equipment suppliers, material suppliers and people. Battery companies all want the same people with the same skill sets. The world wants terawatt-hours per year of battery capacity, and I think you need about one thousand people for every 10 gigawatt-hours. That’s a lot of battery engineers, and there may not be enough to go around in the world. Britishvolt is working on initiatives to collaborate with universities in the UK to foster the next generation of battery engineers to help fill that space. A clear example of how we overcome potential challenges with tailored solutions.

The world wants terawatt-hours per year of battery capacity, and I think you need about one thousand people for every 10 gigawatt-hours. That’s a lot of battery engineers, and there may not be enough to go around in the world.

Ben Kilbey: One of the things we’ve done in the Northeast to counter the human capital challenge is the creation of the Britishvolt FutureGen Foundation. The idea is to take people who don’t have relevant skill sets and train them. They don’t have to come and work for Britishvolt, however our goal is to create a connection with academia and business to ensure that these bottlenecks and challenges have the potential to become future opportunities. And with these opportunities, come solutions.

Charged: Are there other gigafactory projects in the UK that you know of?

Ben Kilbey: The UK already has the Envision plant in the Northeast. There are rumors of more to come.

The Advanced Propulsion Center in the UK estimates that by 2030, around 90 gigawatts of production will be required to satisfy UK demand. Britishvolt’s full production capacity towards the end of the decade will be about 40 gigawatts. That leaves a demand of 50 gigawatts to satisfy.

There is so much activity which is driving the risks around the supply of raw materials. We were already looking at huge inflation. Raw material prices have been going through the roof, and the invasion of Ukraine hasn’t helped. I also think we have to factor in all the gigawatt- or terawatt-hours that are being forecasted or spoken about. How many will come to fruition? We have a clear strategy to partner with the supply chain and ensure we have the correct raw materials, sourced in the right and responsible way, in line with our ESG Principles and Commitments. For instance, our responsibly-sourced cobalt supply deal with Glencore and the recent deal with VKTR for nickel sulfate out of Indonesia.

I think people are starting to realize that making batteries isn’t easy. If it were, then everyone would already be doing it. I think you’ll see a failure rate where people don’t make it to market. But if you look at our world-class team, including Richard, our CTO, Dr. Allan Paterson, and our CSO, Isobel Sheldon, we’ve got a really strong team of people, and the UK ecosystem.

We’re hoping the Britishvolt Effect will bring more gigaplants to the country. So, what we’ll do is create this first business in the UK, and use that as a blueprint to replicate across the world. Ideally, that powers up the whole economy, and other people will come and build their gigaplants and create a holistic ecosystem—the Britishvolt Effect in action.

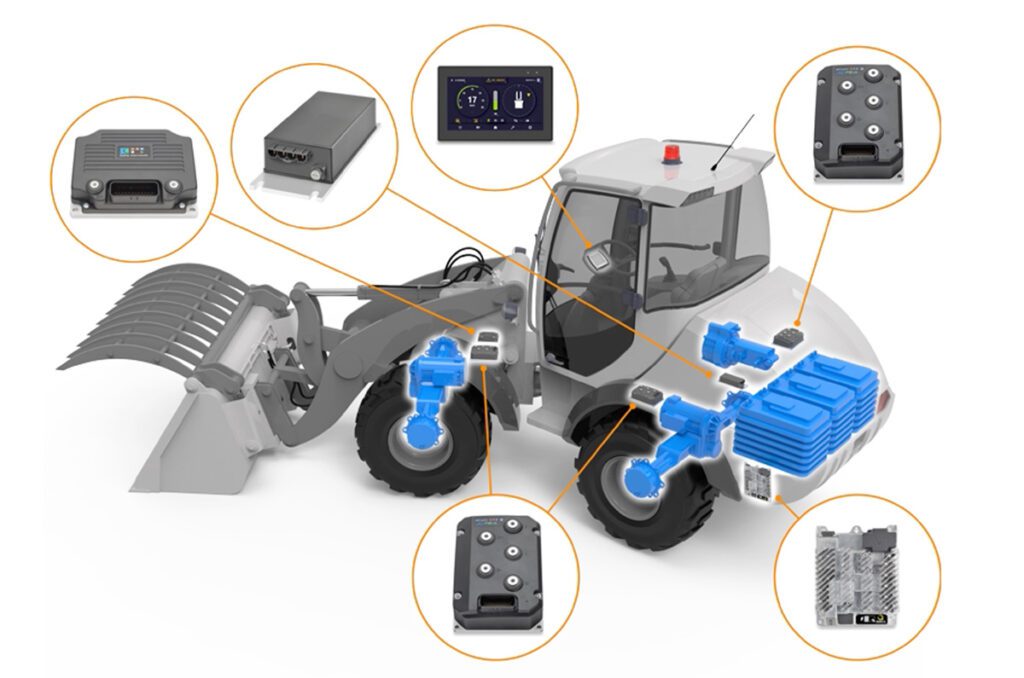

Charged: Once you get into production, are you going to focus on one chemistry and one form factor, or will you be delivering different ones?

Richard LeCain: Britishvolt aims to build a 40 GWh-per-year factory, which we’ll build out in phases. You wouldn’t build a 40 GWh factory all at once based on one form factor and one chemistry, because as the industry evolves, some OEMs will want different chemistries. You want a phased buildout to remain flexible and on the cutting edge. You should end up with a very flexible factory that can accommodate different chemistry types and form factors to satisfy an array of customers.

This article appeared in Issue 59: Jan-Mar 2022 – Subscribe now.