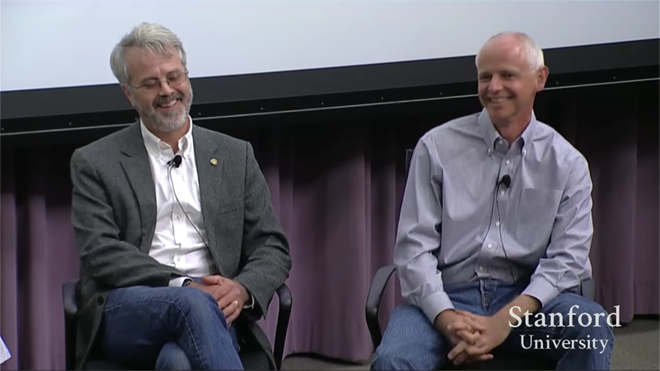

Here’s a treat for any EV fan: a long and meaty talk with Tesla founders Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning, delivered at Stanford last October. While there are several substantial talks with Tarpenning available on YouTube (he also graciously granted me a lengthy interview for my book about Tesla), Martin Eberhard has seldom sat down for a public interview since his controversial departure from Tesla. And as far as I know, this is the only recent video that lets us hear the two engineer/entrepreneurs together.

Eberhard and Tarpenning didn’t start with the idea of building electric cars. “My interest was simply using less energy,” says Eberhard. “I spent some time doing a real careful well-to-wheels energy analysis for every kind of technology I could find, and built a spreadsheet that calculated the actual energy footprint and carbon footprint of every pathway I could find. To both of our surprise, the electric car pathway was not just better than the other choices that were out there – that included hydrogen, every form of petroleum, natural gas and so on – it was dramatically better. It was so much better that it was stunning to us that nobody else was doing it.”

Today, 14 years after the founding of Tesla, there are still people arguing that EVs are no good for one reason or another, and that some other solution would be better. It’s instructive to keep in mind that these two examined all the different options in great detail before deciding to place their winning bet on lithium-ion batteries.

Eberhard tells another wonderful story about their decision to market their vehicles not to penny-pinchers or greenies, but to wealthy car enthusiasts – a decision that may have been the single most important factor in Tesla’s success.

Toyota’s first-generation Prius was an ungainly-looking vehicle based on the Echo, the company’s low-end platform. At $1.20 per gallon, gas was almost free at the time. But to everyone’s surprise, the ugly green duckling started eating into Lexus sales. “Their absolute richest consumers were buying their cheapest car that got the best gas mileage,” says Tarpenning. Toyota had expected to sell the Prius to “a few poor people who couldn’t do math very well [but] it was people who spent far more on lattes than on gasoline that were buying them because they didn’t want to use gas.”

Meanwhile, Eberhard had figured out what Toyota hadn’t. “When I was thinking about ‘Who is our customer for Tesla?’ I drove around the streets of Palo Alto and took pictures of people’s driveways, where you saw a big old BMW or a Porsche parked next to a Prius. And I looked at that and said, ‘That is my customer.’ Someone who likes a fun-to-drive hot car, but also feels bad about the gas mileage.”

Now, you’d think a bunch of Stanford students would go easy on these two elder statesmen, but in fact the questions from the audience covered many of the objections that people tend to raise to EVs. It’s a pleasure to watch two such experienced and well-spoken industry pioneers rebut each of these in an easy-to-understand and factually documented way. If you tend to meet people who, on finding out you own a Tesla, insist on challenging you about things like hydrogen fuel cells, a looming lithium shortage, the “long tailpipe,” etc, some select clips from this video could be handy to have on your phone.

The fuel cell rears its head around 22:00. “Stop me if I start ranting too long on this,” says Eberhard. Hydrogen is not a fuel, it’s a storage medium, and its efficiency, using the best current technology, is around 20-22%, or even 10% when you take the costs of transporting and distributing hydrogen into account. A lithium battery is on the order of 95% efficient. “Your hydrogen fuel cell car will require 3 to 4 times as much of whatever your source fuel is [natural gas, solar, wind, etc] per mile.”

Then why are automakers bulling ahead with fuel cell vehicles? “The reason is that the [California Air Resources Board] in their infinite wisdom has deemed that a fuel cell vehicle gets 10 times as many Zero-Emission-Vehicle credits as an electric car does,” Eberhard explains. “When government mandates a technology instead of mandating an outcome, they almost always get it wrong.”

The dreaded lithium shortage comes up around 19:00. “Lithium is a very common element…there’s a lot of it in places like Bolivia lying around in practically pure form,” says Eberhard. “Lithium is still in the zone of walking around with wheelbarrows and shovels,” Tarpenning agrees. They also remind us that, unlike oil, lithium is not a fuel and is not consumed in vehicles. At the end of a battery’s life cycle, the lithium can be recycled, as almost all of the lead in lead-acid batteries is today. The recycling of lead is well-established in countries around the world, and it shouldn’t be hard to do the same with lithium.

The long tailpipe is likewise snipped off right at the muffler. As many, many studies have shown, EVs generally have lower well-to-wheels carbon emissions than ICE vehicles, even if their electricity comes from coal. Tarpenning and Eberhard explain the physical reasons why this is so. First, electric motors are much more efficient than ICEs. Gasoline is a wonderfully energy-dense fuel, but when burned in an engine, at best 20% of that energy is converted to forward motion. Electric motors are over 90% efficient. Second, utility-scale power plants are far more efficient than the engines in cars, and the electrical grid also has an efficiency of over 90%. Coal may spew more carbon pound for pound than gasoline does, but when used to power an EV, much more of its energy is converted to motion.

Looking to the future, Eberhard predicts that the demise of the ICE is within sight. He’s currently involved with a startup company that’s working on batteries, and he’s seeing “dramatic” improvements in battery performance and cost. “It’s still on a very good curve right now.” Tarpenning agrees: “It’s kind of a slow Moore’s Law – doubling every 7-10 years in capacity, or price, or whatever metric you’re looking at.” Looking solely at the cost curve of batteries, Eberhard forecasts that, by 2020 or 2022, EVs will be cheaper than legacy vehicles. Guess what happens then.

Source: Stanford