Sales of EVs are growing—in some ahead-of-the-curve markets, plug-ins are outselling internal-combustion vehicles—and countries and regions around the world are announcing deadlines to phase out fossil-burners. However, as a recent New York Times article points out, it could take years, if not decades, before electrification leads to substantial reductions in emissions.

The problem, ironically, is that automotive technology has become so good. As every long-time auto owner knows, gas-powered cars and trucks have become quite reliable, and this means that fleet turnover is slow. According to economic forecasting firm IHS Markit, the average light-duty vehicle operating in the US today is 12 years old, up from an average age of 9.6 years in 2002.

“Engineering quality has gotten significantly better over time, in part because of competition from foreign automakers like Toyota,” IHS Markit Analyst Todd Campau told the Times.

Americans buy around 17 million gas-burners every year, and each of those cars and light trucks may be plying US roads for as long as 20 years, after which it’s likely to be shipped off for a second (and dirtier) life in a developing country.

According to IHS Markit’s projections, if EV sales ramp up to 60 percent over the next 30 years, only about 40 percent of cars on the road will be electric in 2050. If electrification is to have the desired effect on air pollution, it may not be enough to encourage the sale of EVs—policymakers need to consider strategies proactively scrap older vehicles, and/or to reduce Americans’ dependence on the automobile by expanding public transit options.

“There’s an enormous amount of inertia in the system to overcome,” said Abdullah Alarfaj, a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University who led a recent study that explored ways to speed up the rate of turnover. The study suggested that policymakers focus on electrifying ride-sharing programs such as Uber and Lyft, and on programs aimed at removing older, polluting cars from the roads.

Senator Chuck Schumer recently proposed a $392-billion trade-in program that would give consumers vouchers to exchange gas-guzzlers for zero-emissions vehicles. A previous program of this kind, dubbed “Cash for Clunkers,” was implemented in 2009, and spent about $2.9 billion to help 700,000 car owners upgrade their vehicles. However, it was widely criticized for evolving into more of an auto-industry bailout—many of the rebates went to drivers who traded in SUVs for newer, slightly more efficient SUVs. “It’s a blunt tool, although there are likely ways to improve the program,” Dr. Christopher R. Knittel, an economist at MIT who has studied the policy, told the Times.

A carbon tax, or an emissions-based tax on new vehicles such as the one that Norway has used to great effect, would probably be a far more efficient way to incentivize drivers to upgrade to cleaner vehicles. However, any proposals with the word “tax” in its title is probably a non-starter in the US, and to be fair, unless it were carefully crafted, any such tax would be a regressive one, hitting low-income drivers harder.

Another, potentially powerful option would be for cities to redesign their housing and transportation systems to reduce dependency on cars, as many European cities have done. One example is the city of Heidelberg, Germany, which has made reducing car dependency a central priority.

Of course, many in the EV industry are predicting a much faster shift to EVs than the decades-long timeline discussed above. Author Tony Seba, among others, believes that once autonomous vehicles become the norm, owning a gas vehicle will quickly become uneconomical. Elon Musk has made similar predictions, saying that once Tesla’s fleet of Robotaxis is up and running, owning a gas-burner will be like owning a horse—something people do for recreation rather than for everyday transportation.

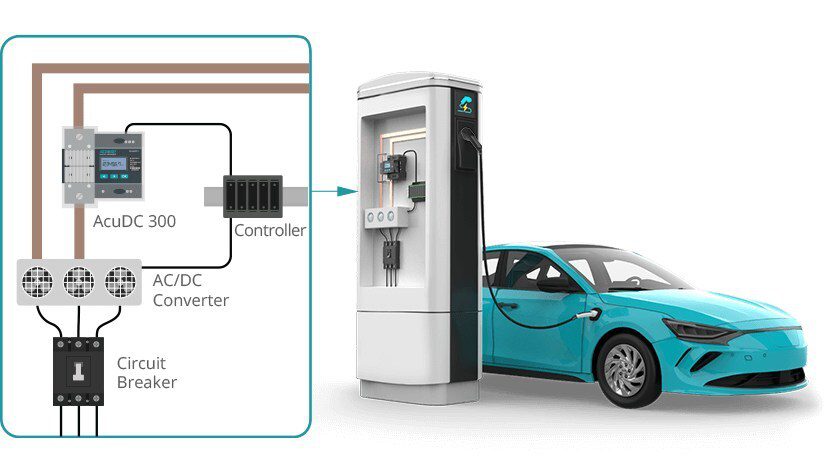

“It would not shock me if the transition eventually starts accelerating,” said Dr. Knittel of MIT. “Right now it can be inconvenient to own an electric vehicle if there are no charging stations around. But if we do get to a world where there are charging stations everywhere and few gas stations around, suddenly it’s less convenient to own a conventional vehicle.”

Source: New York Times