We all acknowledge the absurdity of ignoring an elephant, when one is present in the very room in which important matters are being discussed, but what about a hulking, jacked-up, V8-powered monster truck? Tesla permanently changed the conversation about EVs when it electrified a sporty two-seater, a luxury sedan and a crossover SUV, but few have been talking about plugging in the most popular vehicle in the US.

An electric pickup? There isn’t even a hybrid pickup available from any major manufacturer, although Ford plans to bring a hybrid F-150 to market by 2020. Over the years, we’ve reported on a few smaller companies with electric pickup plans that have delivered with varying degrees of success, including Via Motors, Torque Trends, Efficient Drivetrains and EV Fleet. Trendsetter Tesla has recently announced plans for an electric pickup (Model P?), but its offering is not expected to hit the market for at least four years.

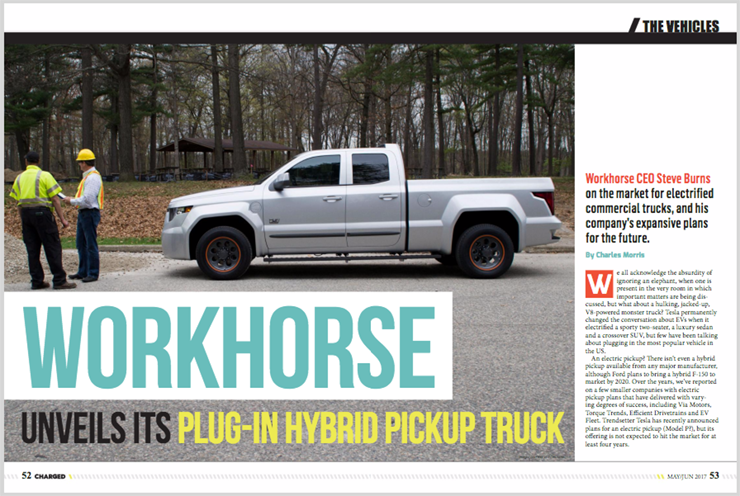

Meanwhile, Workhorse, an Ohio-based public company with about 115 employees, is way past the talking stage. The company recently unveiled a prototype of its W-15 Electric Work Truck, and it already claims to have almost 5,000 orders on its books. Workhorse recently named fleet management specialist Ryder as its primary distributor and service provider for North America. Charged spoke with Workhorse CEO Steve Burns about the current market for electrified commercial trucks, and his company’s expansive plans for the future.

Where are the plug-in pickups?

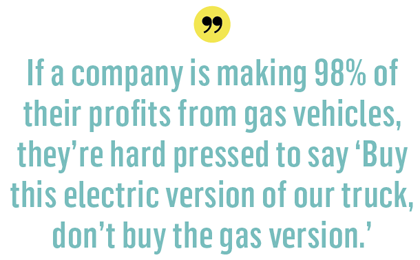

To those who are familiar with the economics of the auto business, it’s pretty obvious why the Big Three have no interest in plug-in pickups. The only thing trucks are better at than guzzling gas is raking in money. The Ford F-150 has been the top-selling vehicle in the US market for 41 years, followed closely by Chevy’s Silverado and Chrysler’s Ram pickup (truck worship is mainly an American phenomenon – on a global basis, the F-150 is second to the Toyota Corolla).

Pickups are not only popular, but profitable. In 2016, CarBuzz calculated that Ford makes nearly $13,000 in profit on every pickup it sells, and quoted industry analyst Max Warburton, who said, “There has been no greater profit machine in the history of industry than the Ford F-Series.”

However, what looks like an unassailable money machine for the big boys could turn out to be a huge opportunity for smaller startups. “This is a classic case where a new fresh idea is not going to come from the incumbents,” Steve Burns told us. “If a company is making 98% of their profits from gas vehicles, they’re hard pressed to say ‘Buy this electric version of our truck, don’t buy the gas version.’”

So far, the truck makers have had no incentive to do anything other than exactly what they’re doing. “The barrier to entry to get to be an OEM is so high that until Tesla came, the big boys could say, ‘Look, there’s no competitive pressure to do this – nobody can get through that gate, it’s too expensive,’” said Burns. “And nobody sneaks up in the automotive world. I come from software, and you’re always worried before you launch your world-changing product that 10 guys in their basements are working on it, and they’re going to launch before you. But in the car world, nobody sneaks up. All the vendors, all the engineering, all the testing…nobody sneaks up and says, ‘We’ve been working on this on the side, and here it is.’”

Focusing on fleets

Workhorse didn’t exactly sneak up, but it has brought its potentially disruptive product pretty far down the road in a short time. The company was established as AMP Electric Vehicles in 2007, and went public in 2010. It started out converting SUVs, but lost faith in the economic benefits of conversion and began to focus on electrifying commercial vehicles. In 2015, AMP acquired the Workhorse brand, along with the company’s Indiana chassis assembly plant, became an OEM and formally changed its name to Workhorse Group Incorporated (NASDAQ: WKHS).

Fleets are the company’s target market, and it has already won several substantial customers for its new W-15 pickup. Utilities Duke Energy and the Southern California Public Power Authority have each ordered 500 units, and so has the city of Columbus, Ohio. Other customers include the city of Orlando, Florida, Clean Fuels Ohio and the truck rental and fleet management giant Ryder System.

Part of the reason Workhorse has been able to log so many orders for its pickup, sight unseen, is that it has already established serious cred in the fleet world as a supplier for Big Brown. Workhorse has been working with UPS for four years. Burns told us that making plug-in versions of the delivery giant’s 20,000-pound brown icons is currently Workhorse’s main business. Each successive order has grown bigger, from 2 units to 18 to 125 to a recent order for 200 announced in October. In May, UPS announced it was paying $50,000 per vehicle, and Burns says the per-vehicle price of the latest order is “comparable.”

“We worked a long time to get that drivetrain solid enough for the likes of UPS vans – very good up-time, and economical enough. We have discovered that fleets look at the total cost of ownership – 8 years of gas and 8 years of maintenance. [Until now] there’s never been anything really better than gasoline.”

What are fleets waiting for?

The business case for electrifying commercial vans would seem to be a slam-dunk, considering the substantial and demonstrable savings on fuel and maintenance. XL Hybrids, Orange EV, Efficient Drivetrains, Phoenix Motorcars, Electric Vehicles International (recently acquired by First Priority GreenFleet) and New Eagle (profiled in the March/April issue of Charged) are just a few of the firms that are vying for a share of this promising market. So far, however, there have been plenty of pilot projects, but few large orders.

Meanwhile, several startups, including Azure Dynamics and Bright Automotive, have starved out while waiting for fleet customers to take the plunge. Via Motors, which sells converted pickups and panel vans, has been around for five years, but has yet to start delivering trucks in large volume.

As observers of the fleet market have told us, the missing puzzle piece is proven reliability. Saving money may be tempting, but dependability is mission-critical. Fleet operators aren’t going to commit to deploying large numbers of plug-in vehicles until they’re 100% convinced that they will get the job done year after year, and for that, they need several years of real-world testing.

Well, those several years of testing are drawing to a close, and the day that plug-ins have proven their prowess should be close at hand. UPS is the undisputed king of commercial fleets, and once it turns the key on electrification, other companies will probably have no choice but to follow its lead.

“UPS is not a bakery that uses trucks – they are a truck company,” Burns points out. “So, they are the hardest to satisfy. There’s no [equivalent to] Consumer Reports, other than maybe Charged, in this space. So, if a fleet wants to know if something works, they look to the leaders. UPS is the largest commercial truck fleet in the United States. So, it took many, many years, and a lot of miles, to build something rugged enough for them, and at a price point they can justify.”

“Green is good – everybody wants to be green – it’s a nice by-product. But we realized that if electric is going to take off, it has to be less expensive than gas. It really comes down to that, at least in the fleet world. A meat-and-potatoes fleet guy says, ‘What is the most economical way I can operate my fleet?’ We come in and tell him we are less expensive than a gas vehicle.”

According to Burns, the reason other companies have failed is that, although they were able to deliver on the gas savings, “the asterisk on that statement is that a fleet has to believe the vehicle is going to last. They have to believe it’s going to last for 20 years. UPS keeps their trucks for 20 years.”

Business is picking up

The new W-15 pickup is a direct descendant of Workhorse’s UPS van. “We took our UPS drivetrain, and essentially shrank it, and put it in a pickup truck,” said Burns. “Although it’s just been a few years with UPS, the grueling nature of the stop-and-go UPS truck, and the fact that they’re buying more each time, indicates that UPS is realizing these are working, [and that] gave us the pedigree to jump into lighter-duty vehicles. Duke Energy was the first to pre-order 500 from us. When we saw the appetite, that people would pre-order a year or two before the product, and before they could even touch and feel, we really saw there was a desire. We got enough pre-orders, we built the concept, and we really believe it’s going to be the start of a sea change.”

What about the competition? “Everybody says, ‘Are you worried about Ford?’ Ford hasn’t even announced [a plug-in pickup]. Tesla, at least, has announced they’re going to unveil a pickup truck in two years, and build in four years.”

Plug-in beats all-electric

“We really don’t think an all-electric pickup truck will work, because of what people put pickup trucks through – occasionally they have to do something very hard,” says Burns. “Tow a lot, haul a lot, climb the side of a mountain, go far. Duke Energy, if there’s a hurricane in Charlotte, all the Duke trucks from all the neighboring states pack up and head for Charlotte. Although they normally go 50 miles a day, once in a while they’ve got to go 400. Once in a while, they put three big transformers in the back. We built this so that it covers our average day, and then we’ve got a little insurance policy up there. [Even] if it’s a weird day, you’re always going to complete your rounds.”

“We found that out with UPS. If you tell a major fleet that this vehicle is really good but doesn’t do all things, you’ve got to be careful where you put it, they don’t want to hear that. They just want it to be ubiquitous. We just say this can do anything a gas pickup can do. 360 days a year, you’re going to get 75 miles per gallon because you’re running it all electric, and the other 5 days, you’ll burn a little gasoline, but the show will always go on.”

The powertrain

Workhorse’s UPS truck uses a range extender engine from BMW – it’s exactly the same one used in the i3, a three-cylinder gasoline engine producing 50 kW of power. “We buy the whole genset from them, the internal combustion engine, the generator, and the computer.” OEMs rarely sell such high-tech components to other OEMs. However, “BMW’s not into trucks, so we’re in a different lane,” says Burns.

The company hasn’t announced exactly what range extender it will be using in the W-15 pickup. “It could still be a BMW, but…it has to be bigger than the i3’s, because to push a pickup truck from New York to California, on one of those weird days, it has to be bigger.”

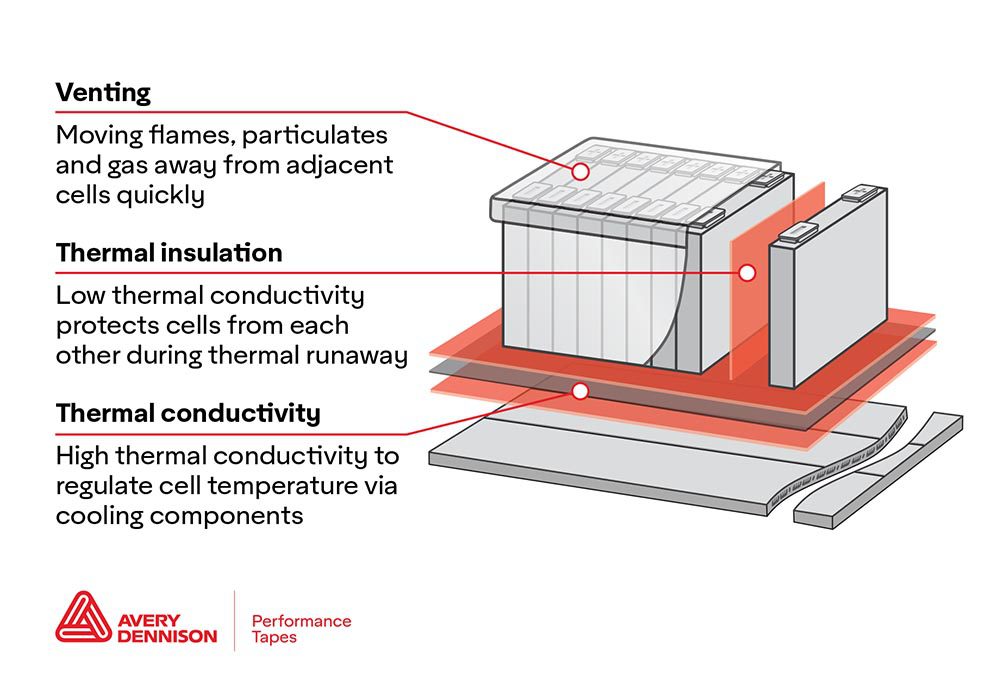

Like Tesla, Workhorse uses Panasonic 18650 battery cells, which it assembles into its own air-cooled and heated battery pack. “Only we and Tesla have been certified by Panasonic to use their automotive-grade cells. It takes a lot – Panasonic has to really test your pack and make sure it’s going to have the longevity and the safety needed.”

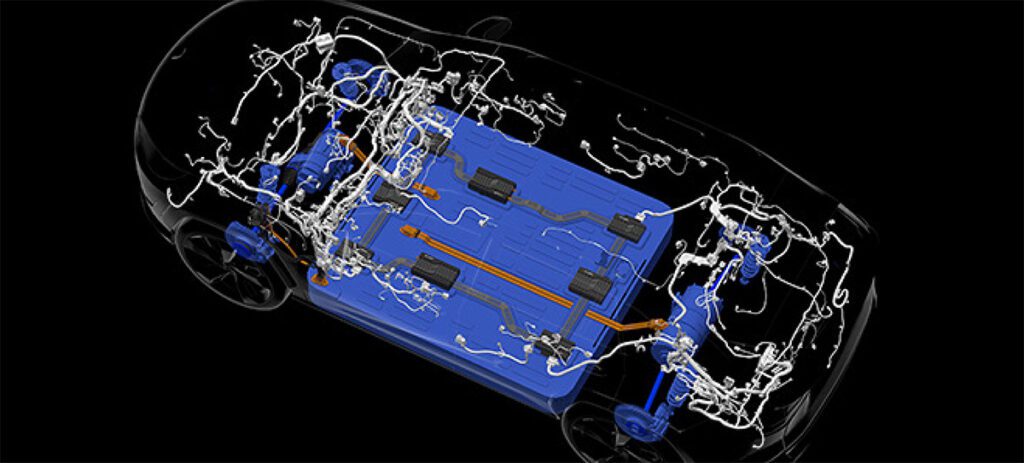

The battery pack is mounted under the vehicle, where it adds rigidity to the truck’s frame. There are front and rear subframes, each with an electric motor, a single-speed reduction gearbox, and a fully independent coil-spring suspension. “The battery pack’s not encroaching on the cargo space at all,” says Burns. “It’s between the rails. If you look at our chassis from a distance, it looks like the dual-motor Tesla chassis – battery in the floor [with] a motor and inline differential on each end.”

Workhorse is using components from familiar companies in order to reassure customers that service and parts will continue to be available. “The reason we use Panasonic cells and a BMW generator is to give a company like UPS, that keeps their trucks for 20 years, the confidence so they can buy the first one, and [know that] Panasonic’s going to make those cells for a long time for Tesla. BMW is going to make that i3 engine and parts for it forever – in 20 years, you’re covered. Those are mainstream commodity parts.”

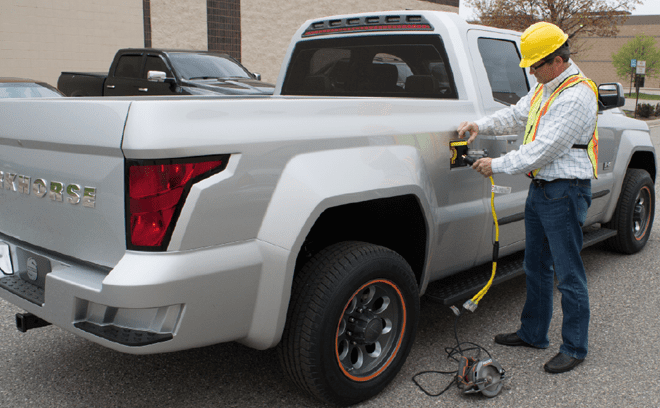

Powering the wheels of the W-15 pickup are two 230 hp/172 kW BorgWarner electric motors, one for each axle. This setup allows for full-time all-wheel drive with active torque vectoring. The vehicle’s top speed is limited to 80 mph for the sake of efficiency. When it comes to charging, the W-15 supports Levels 1 and 2. The initial model will not be capable of DC fast charging, but the vehicle does have a CCS charging port, and a fast charging option is likely to be added at some point.

Workhorse may offer different powertrain options in the future, but to keep things simple, “We’re going to have one product at first. One cab, one bed length, one trim package, one battery pack, dual motor with the range extender.”

Carbon and stainless steel

The W-15’s carbon fiber body and stainless steel chassis delivers what Burns says is the right balance among weight, rigidity and cost. “When you have a carbon fiber body, it’s stiff, right? That lets you require less rails underneath, and stainless steel’s stronger, so you can keep [the chassis] very small and light. [Stainless steel] costs a little more but it’s lighter and smaller [and] the stiffness of the carbon body enables us to use stainless steel down there for the rails. It’s stronger, and will never rust, so you’ve got a body that will never rust – carbon – and then you’ve got stainless steel as the rails.”

When it comes to cost of course, the battery is the main factor. “The key is to right-size the battery. We only have a 60 kW battery, yet we say this vehicle can do anything a gas vehicle can do. If it was all battery, if we had to put a battery in there that could do towing and hauling and go 250 miles, it would be way too heavy and way too expensive. The whole thing is size.”

Workhorse’s announced price point of $52,500 has raised some eyebrows – it seems pretty low for a purpose-built electric pickup. A bare-bones gas pickup costs at least $27,000, and for most fleets the gas and maintenance savings would cover the e-truck’s price premium in pretty short order. Workhorse anticipates that for those keeping inside the 80-mile range of the W-15’s all-electric driving mode, the truck will earn back its premium in just two years. The company projects that over 20 years, a single such truck will save a commercial fleet operator $170,000.

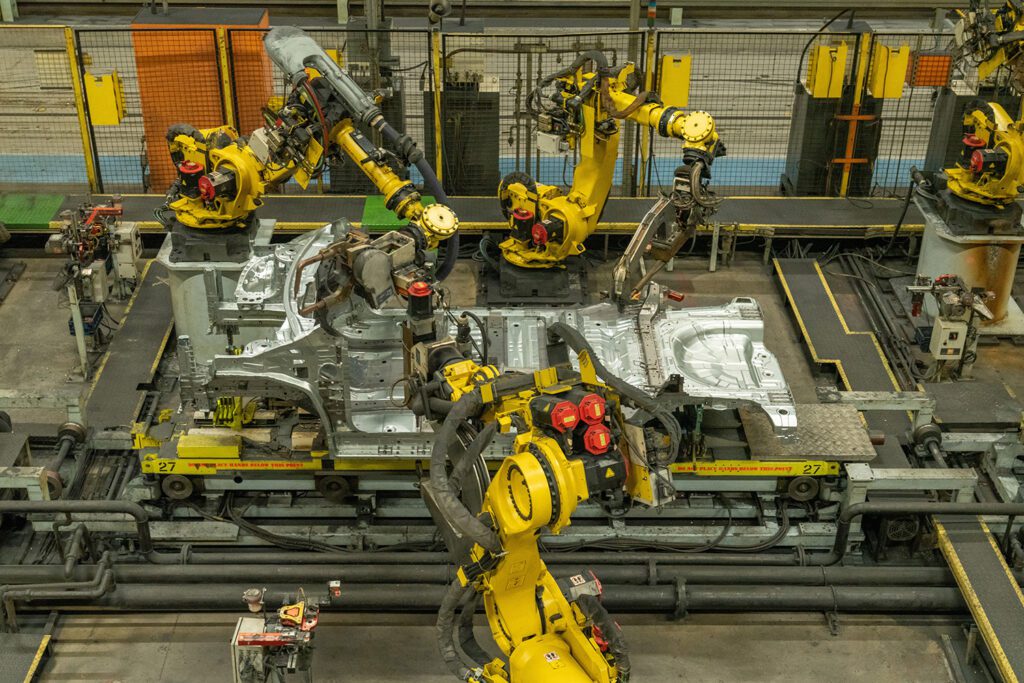

That sounds like a can’t-lose proposition, but how can Workhorse produce its pickup so cheaply? Burns explains that the company has been able to leverage much of the development and equipment for its existing medium-duty truck line. The W-15 will be built in Workhorse’s existing factory, and using carbon fiber means the company won’t have to invest in steel stamping machines, which Burns estimates would cost some 250 million dollars. “Our goal was to get enough pre-orders so that we knew we could make money on the first vehicles, and then pull the trigger. The thing we’re saying out loud now is we’ve received enough pre-orders to commit to the production.”

Built for the modern worksite

The W-15 features a light bar with yellow hazard lights, a sprayed-in bedliner and a power export module that delivers 7.2 kW, enough to power a job site. All the latest high-tech goodies are here, too: most of the vehicle’s functions are controlled through a touchscreen (which is designed to work even with gloves). Workhorse’s Metron fleet management software sends the truck’s location and condition to fleet managers in real time. All the truck’s software can be updated over the air. Safety features include collision warning, emergency braking, lane departure warning, and lane keep assist, as well as adaptive cruise control and a full complement of airbags. Workhorse hopes to achieve the highest-ever safety ratings for a pickup.

Going native

Workhorse is the first company to build a plug-in pickup from the ground up rather than convert an ICE truck, as Via Motors and a few others have done. Burns and his team are convinced that this is by far the better way to go.

On the face of it, converting an existing truck sounds like a good way to save money and avoid “reinventing the wheel.” Other than the engine, transmission and gas tank, most of the other bits of a vehicle – body, interior, lights, electronics, wheels, suspension – can be the same, regardless of the powertrain. However, this approach requires the designer to make a series of compromises that trade away many of the benefits that an electric powertrain can offer. Tesla built the Roadster on a Lotus Elise chassis, but Elon Musk later said that it was “actually an incredibly dumb idea.”

Burns strongly agrees. “We started like Via Motors…we were a converter, because being an OEM, the bar is so high. A lot of us had the same idea ten years ago – let’s convert vehicles. But it’s a tough sell to customers, a converted vehicle, because they know it’s doing something different than its original purpose. A fleet says, ‘Look, if a frame rail breaks, who do I call? The company that originally made it?’ They’re going to say, ‘Well, it broke because you hung a heavy battery pack on it.’ If a control center for that gasoline engine was built not knowing that somebody was going to bolt something onto it later, because it’s already been CARB-approved and EPA-approved, you can’t mess with the software. It’s a tough road – in general I don’t think any conversion company ever made it. It’s impossible to make the numbers work.”

“[Converting] ends up being more expensive, because you’ve got to deal with the hand you’re dealt. That hand wasn’t built for what you wanted to do and then you just wind up compromising, and this is a world where everything’s got to be 100 percent for its purpose.”

Burns and his team had an advantage that other would-be truck builders didn’t – they were able to buy an existing truck OEM. “We bought Workhorse. They were making medium-duty vans and RVs. That enabled us to get a jump on being an OEM, taught us how to handle the factory and the brand and all the electrical problems. We couldn’t have really done it without that. Carmakers don’t come up for sale often.”

The Workhorse W-15 will go into production in late 2018 at a price of $52,500, and it will qualify for the $7,500 federal tax rebate. Burns won’t say exactly how many units the company plans to produce per year, but Workhorse’s factory has an annual capacity of 60,000 vehicles.

Any plans to eventually sell to consumers? “Well, I would’ve said no to that a little while ago, but a couple of things are happening. It’s really good looking – we built it to be modern and professional-looking. We have some aerodynamics to it because we’re worried about energy. Some of our customers wanted a lower hood so they could see pedestrians easier. All that combined into a very unique-looking pickup truck, good-looking enough that every consumer that sees it says they want one.”

This article originally appeared in Charged Issue 31 – May/June 2017 – Subscribe now.