The prospect of zero emission, near-silent race cars has set moustaches twitching throughout the motorsport fraternity. Many see it as heresy, while the enlightened few realize that we have a golden opportunity to inject some new life into a hundred-year-old sport.

Doug Peck, editor at emotorsportnews.com, explains why the future of racing runs on batteries.

The thrill of racing has been a part of human culture ever since the ancient Babylonians pitted steed and rider against each other in the first organized horse races.

These days our anthropological need for speed has translated into events like Formula One, a lamentable circus characterized by cronyism and crippled by bureaucracy; it’s not hard to understand why a handful of EV evangelists are taking matters into their own hands to shake up the system and demonstrate why the internal combustion engine is as prehistoric as its fuel.

The story of electric motorsport goes back to 1896, when an electric car built by the Riker Electric Motor Company soundly beat its petrol-powered rivals in the first ever automobile race in the US. Seven cars (five petrol, two electric) wheezed and chuntered their way around a dirt oval track at the mile-long Narragansett Trotting Park in Cranston, Rhode Island. Incredibly, the electric competitors took first and second place – beating the best internal-combustion car by over three minutes.

The story of electric motorsport goes back to 1896, when an electric car built by the Riker Electric Motor Company soundly beat its petrol-powered rivals in the first ever automobile race in the US. Seven cars (five petrol, two electric) wheezed and chuntered their way around a dirt oval track at the mile-long Narragansett Trotting Park in Cranston, Rhode Island. Incredibly, the electric competitors took first and second place – beating the best internal-combustion car by over three minutes.

You’re probably wondering why this comprehensive victory for the volt didn’t spur on an electric revolution in transportation, but with oil prices crashing to just pennies a barrel, it was all over for the electric race car.

That is until 1994 when John Wayland astonished the drag racing scene by competing in his electrically powered White Zombie, a 1972 Datsun 1200 converted to run on aircraft starter batteries and a nine-inch DC motor.

John Wayland’s record setting White Zombie, a converted 1972 Datsun 1200

Photo courtesy of Plasma Boy Racing.

The incredible levels of torque it produced soon alerted other drag racers to the potential offered by electric drive, and now the National Electric Drag Racing Association (NEDRA) boasts hundreds of members. In 2007, Pro EV’s Electric Imp was the first EV in over 100 years to win a sanctioned road race against petrol-powered cars, setting the stage for a renaissance of the electric motor in racing.

But what is the point of motorsport anyway? Isn’t it a waste of resources and a huge carbon emitter? Not really, on both accounts. Motorsport has been a consistent contributor to advancing technologies, including material science, aerodynamics and safety.

The aerospace, defense and marine industries have all benefitted, and the modern car would be unrecognizable if it weren’t for innovations such as disc brakes, traction control, ABS, fuel injection, crumple zones, independent suspension, turbo chargers – all of which were tested and proven on the track. In terms of the race teams themselves, they are all very aware of their reputation as polluters and are actively seeking out carbon neutrality, but it is the fans themselves who travel in their thousands to the events that are the real problem. As you’ll read later, electric racing has an answer to this problem as well.

I’m sure you know that OEM car manufacturers are under severe legislative pressure to lower their impact of their products on the environment, and face multi-million dollar fines for non-compliance. Some, like Aston Martin and their Cygnet, are finding innovative ways around this, but the majority are hastily investing in hybrid and electric drivetrains for mass market cars. They don’t really want to, because EVs have historically suffered from image problems as slow, boring and sanctimonious methods of transport. The Prius aside, EVs and hybrids of all persuasions have had disappointing sales results across the board.

Enter, stage right: Mr. Motorsport. It has always been the case for car manufacturers that you “win on Sunday, sell on Monday,” so the OEMs are now looking to their old friend the racetrack to sex up those pesky green cars cluttering their forecourts.

Up the Hill

Of course it’s not only a marketing exercise – as with traditional racing, there is a great deal to be learned from testing out electric drivetrains and cell chemistries in the highly demanding motorsport environment, much of which can be applied to consumer vehicles.

For example, Mitsubishi is preparing a special version of the i-MiEV to tackle the treacherous Pikes Peak International Hill Climb this year. This will not be a highly-tuned, high horsepower car, but one that shares the majority of its drive components with the road car, albeit cocooned in a much lighter, pared down skin.

This enables Mitsubishi not only to promote the i-MiEV in its own right, but also to push the critical components to the limit to find that extra mile per watt-hour, or minimize losses due to heat.

The same goes for Nissan’s NISMO LEAF, which is essentially a carbon fiber version of the consumer car, packing the same power output and cell pack.

Both of these examples are a toe in the water for manufacturers, born ultimately out of government pressure, but it’s not just the OEMs who are feeling the sharp end of emissions legislation.

Also headed up the hill in July are a handful of custom EV builders, like Southern California’s EV West in their converted 1995 BMW M3. Since John Wayland awoke the tinkering world to the possibilities electric power, many independent racing fans have joined the e-party.

EV West’s 1995 BMW M3 electric conversion

Photo courtesy of EV West.

EV West also has its eye on the new Ultra Green class of the Baja 1000.

Formula E

The Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) governs world motorsport, and was told in no uncertain terms by the European Commission that they had to create a new series based on alternative propulsion. You cannot imagine how much this must have riled the old guard, who would rather send a Maserati Tipo 61 Birdcage to the crusher than pander to the eco-warriors. After some protracted beard stroking they came up with Formula E, an electric race series modeled on the current Formula One format that will see a grid of up to 24 electric cars in a global competition.

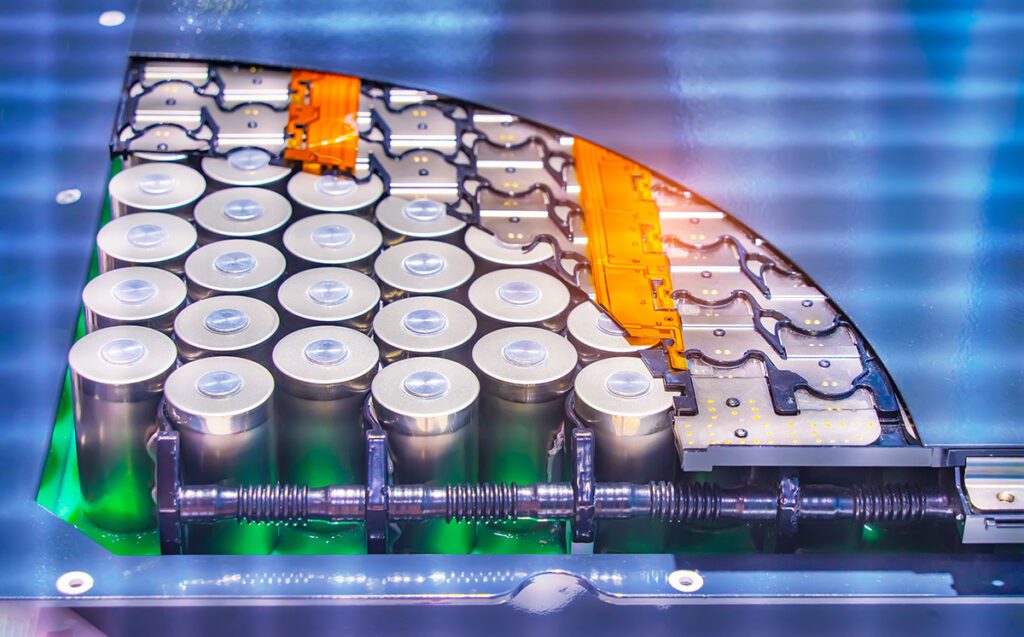

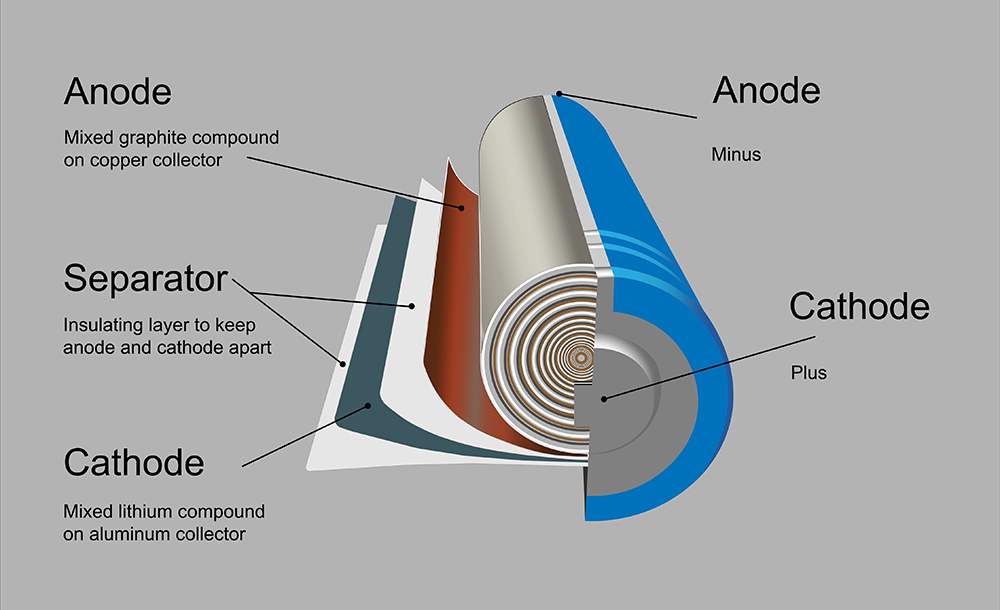

As an organization that has solely focused on the internal combustion engine for the last 108 years, they were blissfully unaware of the two major limitations of electric racers. Even with the most energy-dense cells available, range is still limited to around 20 minutes of racing – any more capacity and the size and weight of the cells interferes with the dynamics of the lightweight cars. Moreover, designing a gearbox that can handle the torque from race-spec electric motors is still challenging engineers, so most cars operate direct drive, which limits their top speed.

Formulec’s EF01 has demostrated a 0-60 run in under three seconds and a top speed of 210 mph.

Photo courtesy of Formulec.

Despite this, the FIA proclaimed Formula E as a “new kind of F1” that would be faster than the petrol variants, and it has taken a concerted effort from companies such as Kleenspeed, Formulec, Quimera and Drayson Racing Technologies to bring them back down to Earth.

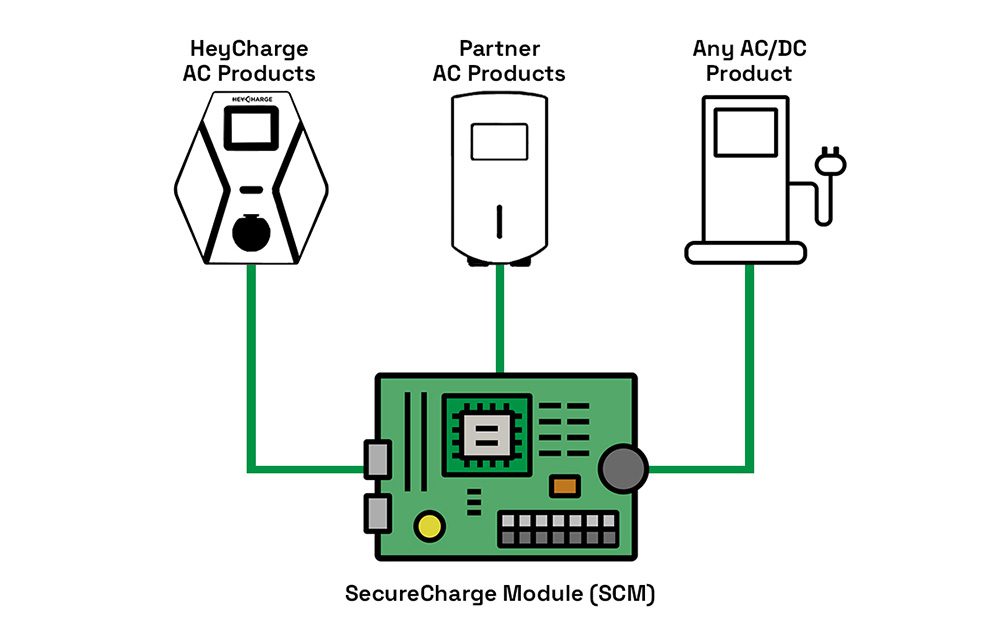

As they now realize, Formula E will never be an F1 replacement. Details as to how race weekends will be structured are still being negotiated, but it is envisioned that like most other electric race series, short heats of around 15 laps each will be contested. There is no news either on whether longer races might be facilitated through hot swapping battery packs, or even if they are considering wireless inductive charging options. We wait with bated breath.

Thankfully, Formula E is on track to launch demonstrations in 2013, with a full series planned for 2014. The rules are fairly straightforward in terms of technical specs: minimum weight of 780 kg, maximum battery pack of 300 kg, and the car must be able to run for at least 18 minutes at full tilt.

Performance from the initial prototype test cars like the EF01 from Formulec is, if you’ll excuse the pun, electrifying. The 0-60 dash is achieved in under three seconds and they will go on to 210 mph (340km/h), with torque levels in the 1000s of N/m. Several consortia are currently pitching the FIA to build these cars, but there is one fly in the ointment – noise.

Did you hear something?

Ask most petrol heads what they love about motor racing and two aspects always come up – the sound of the engines and the smell of the fuel.

The FIA are desperate not to alienate their fans, and although they can’t exactly pump gasoline vapor around the tracks they are putting a great deal of emphasis on making sure there is some kind of soundtrack to the races.

Indeed, this March at a press conference before the Melbourne Grand Prix Gerry Connelly, VP of the FIA Institute, commented, “One of the challenges (with Formula E), of course, is how to get some noise, because the idea of putting in sound is a bit of a conflict of ideas. It’s not actually very safe to have silent cars, so they’re working out something where there will be noise generated, but it won’t be like the current Formula One.”

Personally, I think this could be very damaging for the sport, as we don’t need to give any more ammunition to the racing fans already making jokes about slot cars when talking about electric racing.

The lack of noise could actually turn out to be Formula E’s greatest strength. Unlike their raucous cousins, electric race cars can be run on street circuits in city centers other than the hallowed circuit at Monaco. This brings racing directly to the fans, cutting out the travel (hence carbon) and is more family friendly – allowing young children to attend without the ear defenders that are such a necessity at F1 events. Races will be largely free to attend, tempting in a new untapped audience curious to see high technology put through its paces on their doorstep This in turn attracts a whole new raft of potential advertisers and sponsors keen to position their products in front of this tech savvy, environmentally conscious, early adopting audience.

Drafting

Formula E is not the only option if you fancy some high-speed EV thrills. The EVCUP was arguably the first on the scene, touting the futuristic-looking Westfield iRacer and offering a race event that would include green technology showcases, live music and celebrity endorsements (they have strong ties with talent agents CAA) as well as the actual races.

Unfortunately, due to technical issues with the prototype iRacers – which reportedly weren’t fast enough and ran too hot – they have postponed the inaugural race until further notice.

Quimera’s AEGT (All Electric GT) sports three UQM motors delivering 700 bhp.

Photo courtesy of Quimera.

One of the most exciting prospects is the new electric-only series to be jointly run by the International Motorsport Association (IMSA), American Le Mans Series (ALMS) and clean tech pioneers Quimera Group. They will be running a number of different classes of EVs including drift cars, touring cars, Le Mans prototypes (LMP) and even a Formula One style car that is set to be a direct rival for Formula E. All of these cars will run on the same day in short 20-minute heats, providing plenty of entertainment in bite-size, media-friendly chunks.

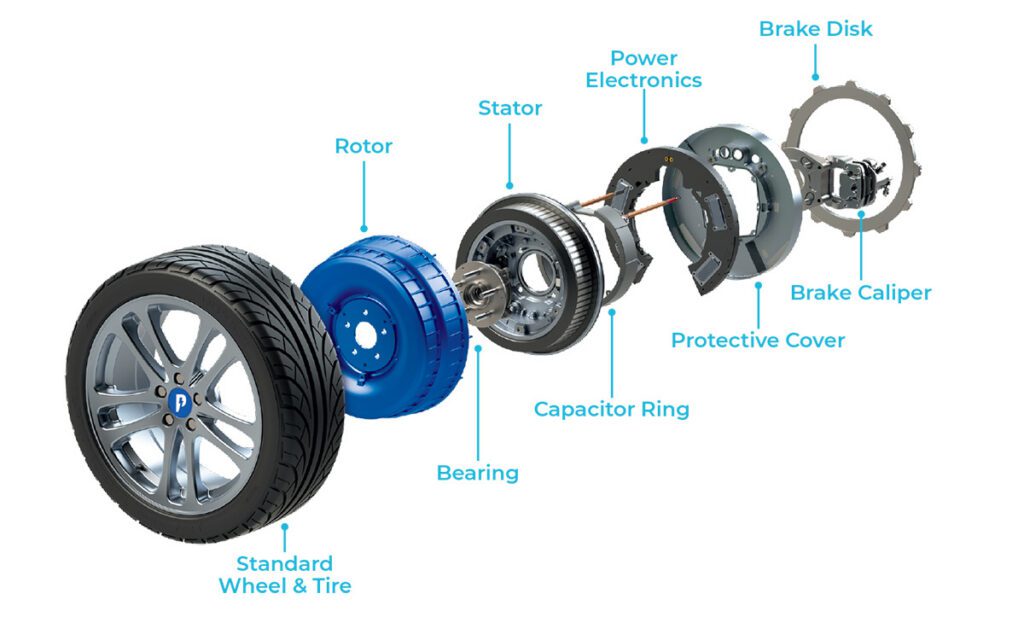

Quimera’s All Electric GT car (AEGT) will be showcased at the ALMS events this year, and it should make a few jaws drop. With over 700 bhp, this engineering marvel has three UQM PowerPhase HD Select 200 motors linked up to a Hewland sequential gearbox – dealing with 1000+N/m of torque would make most transmissions run for their mummy. Power comes courtesy of LiPo packs supplied by EIG of South Korea. Although they are tight-lipped on capacity, energy density is around the 170Wh/kg level, giving around 20 minutes of flat-out racing.

Pulling ahead

No article about electric racing would be complete without a mention of the incredible LMP car built by Drayson Racing Technology in the UK. The B12/69EV has been assembled with the support of racing veterans Lola and employs truly groundbreaking technology like structural batteries, on-the-fly inductive charging and recuperative dampers. It is claimed to run at over 200 mph, and judging from the stats it shouldn’t have any problem. Four YASA 750 motors deliver a hefty 640 kW (850 bhp), and it weighs in at 1085 kg including driver, allowing it to make 60 mph in 3 seconds and 100 mph in 5.1 secongs.

The Lola-Drayson B12/69EV boasts over 850 bhp from its four YASA 750 motors and 60kWh pack of A123 cells.

Photo courtesy of Drayson Racing Technologies.

The three cell packs have been supplied by Mavizen and are made up of A123 Systems cylindrical ANR26650MIB nano-phosphate cells, giving a total energy of around 60 kWh running at 700 V max. It has not turned a wheel in anger yet though, and as it uses the same motors as the beleaguered Westfield iRacer will it suffer from the same overheating issues? Only time will tell, but judging by the snakes’ wedding of cooling pipes under the cowling I think they should be okay.

2012 has constantly surprised the EV community with ever-advancing battery and motor technology, and this will only speed the adoption of electric propulsion in the racing community. The torque characteristics of electric motors lend themselves perfectly to pushing out of corners and rapid acceleration off the line, and the noise of an electric car at full chat is like a quiet jet turbine – reassuringly futuristic. I for one can’t wait for more people to get behind electric motorsport – it offers a bright future for fans, car companies and our fragile planet.

Issue: APR/MAY 2012