There are a lot of great opportunities for companies building EVs for niche markets, but getting an independent automotive startup off the ground is anything but easy.

EVs can be very practical from a financial point of view. So it’s a bit of a shame that for the world’s most practical vehicle buyer – the fleet manager – there are still not many options, particularly in the popular segment of small to mid-size vans and trucks. If a commercial application can’t be fulfilled with a passenger plug-in vehicle – like a LEAF or Volt – there are few other choices for a fleet buyer who is looking to reap the cash savings from driving on electronics.

Some major automakers have offerings for the commercial market, like Nissan’s e-NV200 van and, in Europe, Renault’s Kangoo Z.E. But for the most part, the large OEMs see the commercial market for small trucks and vans as too small relative to passenger cars. So when automakers decide to spend billions on electrification technology development, they’re focused on creating the next Prius-style success story. It will probably take another decade for the EV technology currently being developed for high-volume consumer EVs to trickle down to widely-available commercial trucks and vans of many shapes and sizes.

A few companies look at this reality and see a huge opportunity. For example, Charlotte, North Carolina-based EV Fleet, which has designed a highway-capable light-duty all-electric truck called the Condor, with a variety of bed options to meet the needs of many commercial customers. The company has spent the past few years using early prototypes to quietly build interest among commercial and municipal fleet operators, and it reports enough commitments to max out production for years to come. Charged recently connected with CEO Brooks Agnew to learn more about the potential market and the last obstacles the company needs to clear before starting full production.

Charged: We’ve seen quite a few independent companies that have launched EVs in the medium- to heavy-duty commercial space. What led EV Fleet to choose the light-duty market?

Brooks Agnew: I’ve been in the auto manufacturing business my whole career, about 23 years, and in 2007 I decided to look into starting an EV business. Around that time I began to notice that all the small trucks (like the Toyota Tundra, Chevy S10 and Ford Ranger) were being discontinued by the automakers. And these were the trucks largely used in commercial fleets (carpenters, plumbers, electricians, delivery, municipalities and service vehicles of all types). Light trucks were very popular commercially because they’re more economical on fuel, cheaper to acquire and still very versatile. And yet, one by one those models went out of production and the car companies moved that customer base up to mid- or full-sized trucks.

As Detroit and Japan backed out of that market, I looked at it and thought, “Now there is a good operational model into which electric pickup trucks would fit perfectly.” And after two and a half years of test-driving our vehicles with all kinds of different potential customers, this is exactly what we’ve found. We listened to the voice of the customer and designed a truck that drives exactly like a gas-powered truck, and they’re very interested. The Condor was designed by our customers.

Charged: Can you tell us about the design and specifications of the Condor?

Agnew: Like many other new EV companies, we started doing gas-to-electric conversions. We thought it would be best if we could find someone to sell us gliders – a fully operational automotive frame with no engine or gas components at all. However, I found it nearly impossible to find a supplier. There were some options for importing them, but that was a time-consuming and expensive process, thanks to some EPA regulations. The only option for upgrading ICE chassis to pure electric drives was buy a new vehicle, strip it out, and turn it into electric. We quickly determined that the financial model wasn’t there for that type of operation.

Instead, we gathered the best racing minds together and started to design the Condor from the ground up as an electric truck. I’m pretty familiar with just about every major aspect of automotive manufacturing – I have been through the APQP process with many platforms. I became a Six Sigma Master Black Belt and coupled that with Lean Manufacturing skills over a 10-year period to develop a systemic approach from the beginning.

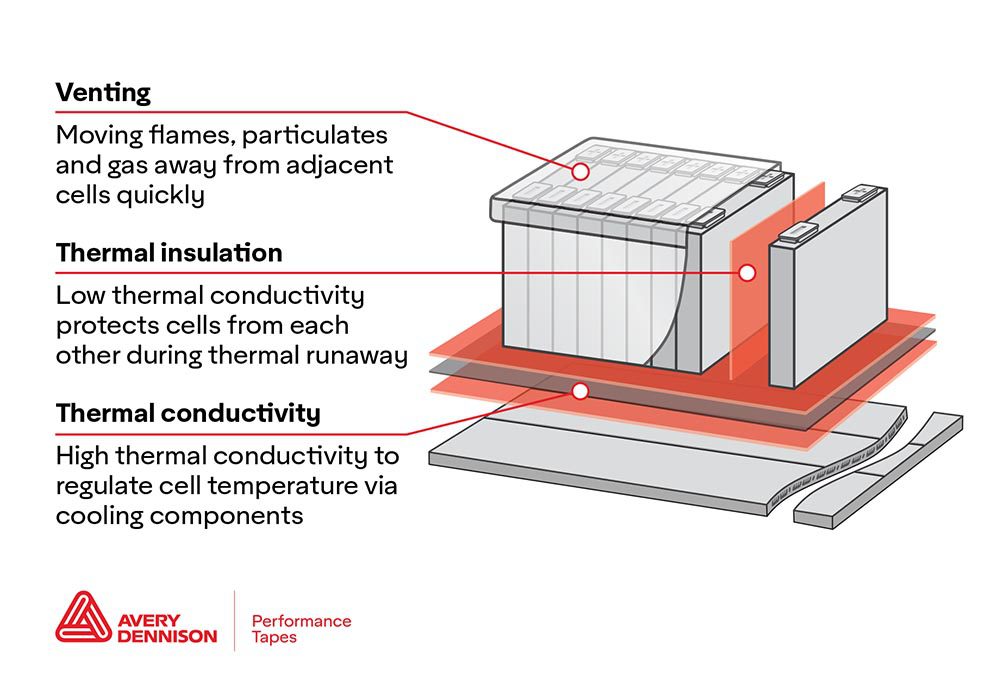

In 2013, we started by designing our own lightweight, high-strength steel frame. It has a 127-inch wheelbase, and is designed to protect the batteries in case of a collision, which makes the truck extremely strong. Also, one of the reasons small trucks went out of production is that the design was fundamentally unsafe. If there is no weight in the back of the truck, the vehicles had a tendency to oversteer – actually have the rear wheels lose traction at freeway speeds in wet conditions. Our design solved that inherent safety flaw, because we distributed the battery pack along the frame, so it maintains traction even when it’s empty. The Condor may be the safest small truck in America, partly because of its low center of gravity, so it will resist rolling over, and its evenly distributed weight, so it won’t get stuck, even in icy conditions.

The Condor has a fully independent suspension, 4-wheel disc brakes, and a minimum of 8 inches ground clearance. The clearance can also be adjusted up two inches by the owner if you have something like an off-road application. The drivetrain has 70 hp to the wheels and a 5-speed transmission. If you need to tow something, or climb a hill, you’ve got the torque to be able to do that, or if you want to do freeway driving up to 85 MPH, you’ve got the gearing to do that – all in the optimum torque band of the motor, which helps extend the range. The first thing drivers notice is that the acceleration is better than a gas-powered truck. I often say that we have a device that holds you in the seat – it’s called the motor.

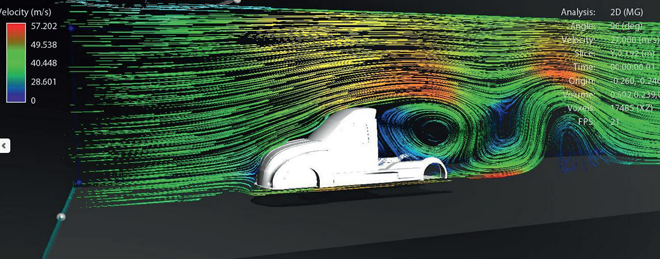

We have two battery options: a 50 kWh pack for $49,900 and a 30 kWh pack for $46,500 (before tax savings). In our urban tests with continuous driving over 45 mph, we’re getting 120-135 miles per charge on the 50 kWh pack. That’s on what we would call normal city streets. For the 30 kWh pack, we’re seeing a consistent 60-70 miles per charge. The excellent range is due to the smooth body design that slips through the wind with drag coefficients more like a sports car. The patent-pending drive system is tough and extremely low on mechanical drag, making the coast-down numbers the best in its class. Once you reach the posted speed, it takes surprisingly little energy to maintain that speed.

For companies that do a lot of short trips, like car parts or flower delivery, utilizing a charger back at the depot for opportunity charging, the 30 kWh pack is a great option to reduce the upfront costs without compromising the performance at all. Since they’re never more than 25 miles from the shop, it works out perfectly.

The vehicles come standard with a 3 kW onboard charger for Level 1 or 2 J1772 charging, or we can upgrade it to 5 kW. All Condors come with both 120 V and J1772 ports so they can recharge anywhere. They are even equipped with built-in solar recharging, to keep the batteries topped off even when they’re not plugged in. The cargo cooler version with solar power stays cold all day, supported by free energy from the sun. We can also enable the vehicles to work with DC fast charging, however after years of test drives and talking to customers, we’ve never had someone interested in anything over Level 2. No one in the light truck fleet market seems to care about rapid charging. They’re happy not to be deep cycling the pack, and to use opportunity charging 4 or 5 times during the day in combination with overnight charging. That fits their operations model. The Condor also has the ability to transfer energy to another Condor in case of emergency.

We’re working with multiple suppliers for the batteries and the charging systems. Part of our design criteria was to create a generic battery space, so that we can fill it with the best battery technology at any time. That sort of competition makes sure the customer has the best available technology. We’re now using a state-of-the-art lithium iron phosphate battery that has great watt density. They’re designed to last about a decade in the vehicle and then be sold to the second-life market, recovering some of the customer’s investment in batteries. And our nearly bullet-proof motors are from a supplier in Chicago that builds them to our specs. With less than a dozen moving parts, the Condor may last a lifetime requiring very little maintenance. It uses no oil, water, or fuel. That’s why we say, “No grease, just lightning.”

Charged: Will the Condor be eligible for the $7,500 federal tax credit when it goes on sale?

Agnew: Yes, as soon as it receives approval from the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS) it will qualify for the $7,500 federal credit. The credit is based on a minimum battery size – which the Condor meets and exceeds – and only applies to vehicles that are capable of highway speeds – no problem for us with a top speed of 85 MPH.

Also, when designing the vehicle, we thought that sooner or later Washington would lose its appetite for this tax credit system and it would go away. So, we had to design a truck that could compete dollar-for-dollar (without tax incentives) in a 36-month period with a gas-powered truck. And that’s why we targeted $49,900 for the 50 kWh truck.

Charged: At what stage is the Condor in the FMVSS and crash-testing process?

Agnew: We finished crash-testing the vehicle structure in January of 2015. So, the truck is completely crash-worthy – rollover, side impact, rear impact, frontal impact. It was an iterative process. We crashed the truck, then made improvements and crashed it again until we had a good margin of safety. The cab has an integral steel roll cage that is far stronger and safer than any small truck ever built.

Our last step is to design and test the smart airbags in the two front passenger areas and side curtains. We were working with an airbag company that encountered a major recall part of the way through the process, so we had to change companies. That has definitely been a setback in terms of timeframe and costs. The price of airbag development essentially doubled when we switched suppliers, from about $4 million to almost $9 million. So, right now the only thing between our factory floor and customer deliveries is finishing airbag design and testing – a process that takes between nine and twelve months.

Airbag design happens in three phases. First the bags are designed electronically, that takes about two months. Then prototypes are physically sewn together and put into one of our cabs, which is bolted to a sled. At that point it’s not crashed but reverse accelerated at a very high rate, so the bags are deployed. That happens over and over again inside the cab with high-speed cameras recording, so the controller can be programed to unfold the bags in the optimal way for each test dummy style and position. Once that programming is done, which usually takes about 4 months, the finished truck is physically crashed containing the airbags. If the physical crash meets the simulation, then it’s considered compliant. They rarely have to do the full crash more than once for each approach, because the initial design steps are so comprehensive.

So we’ve already contracted the new airbag supplier, and we’re currently working on a new round of financing to cover the additional costs.

Charged: Are there other regulatory hurdles, beyond crash testing, that are particularly challenging for a startup EV company?

Agnew: There are several agencies involved, not the least of which is the EPA. You could ask yourself, why in the world would the EPA be involved in electric cars? It’s not really their space since there are no emissions, but, believe it or not, they still do the exact same testing as they would with a gas-powered vehicle – except they don’t have a tailpipe to stick the testing probe in.

The EPA has created a Fuel Economy Label for EVs that contains 14 indices that I think are meaningless to consumers, which is why they naturally ignore them. The label is expensive and takes months to obtain, because the EPA has only one testing station in the entire country. The application process was created for ICE vehicles, and has no provision for EVs. They don’t claim to know how to drive an EV, nor will they shift gears during their dyno testing process. And if they get it wrong and report a much lower range than the manufacturer claims, there is no appeal process.

In fact, one could say we already have a “fuel economy label” that’s very simple to understand, and tens of millions of Americans are already familiar with it. Every time you buy an electric appliance there is a yellow label on it that says, “This appliance costs approximately X dollars per year to operate.” And that’s the fuel economy label we have on our truck window, and it’s one everyone understands.

We are actually talking to Congress on a regular basis to try to correct the EPA process and hope the other EV producers will join us in trying to lift some of the misguided regulations that have prevented EVs from reaching a hungry consumer market. I would estimate that together, EV producers represent about 20,000 jobs that are badly needed in places like Charlotte.

Charged: Can you describe how you see the Condor fitting into the commercial fleet buying process?

Agnew: The way most fleets work is that they replace a certain amount of vehicles every year. As the trucks get a little over 5 years in age they look at the maintenance record and the mileage, and then send them off to the auction block, where they don’t get very much money back. Then they buy new vehicles.

These are the customers we’re talking to about getting our vehicles on the replacement schedule. Small orders at first: 5 to 10 trucks. Then, as they see those succeed at the application, during the next purchase cycle – usually six to nine months later – they’ll be more inclined to purchase more electric trucks: around 10 to 20. These numbers are based on the fleet operators that we’ve been working with to put together a 5-year schedule. We asked them, assuming success with the truck and a good service relationship, what amount of your gasoline fleet would you replace with a successful electric fleet? And the response has been incredible for a company our size. We’ve found very real interest both in terms of writing us checks and giving us letters of interest to reserve their spot in line.

We did a study with one national supply company that wanted to know the fuel cost reduction if they replaced 6,000 vehicles with electric trucks – that’s only a portion of their fleet – and it was in the neighborhood of $30 million in annual savings. So, electric trucks can clearly be compelling for a lot of fleet applications, and we can outfit the vehicle backend with a lot of different options for any use case – a box truck, refrigerator, freezer, flatbed, storage, etc.

Charged: Do you have any advice for other people who are thinking about starting an independent EV-related business?

Agnew: One of the hardest things to do in life is start a company, whether you’re starting a restaurant or a manufacturing business. The access to capital is as hard for one person as it is for another, and fundraising can be almost as hard as designing the products.

However, this is an exciting time for the EV industry. This is where the industry begins to break away from the restraints placed upon it by incumbent interests. If you think about it, the major automakers don’t care whether EVs come or don’t come. They’re still selling with the same tire smoking, sideways drifting car ads. If a major automaker sells you an EV, it just replaces an ICE car they already make. What keeps them dabbling in the market is the fear of missing out on the next big trend, and that trend is here.

This article originally appeared in Charged Issue 22 – November/December 2015. Subscribe now.