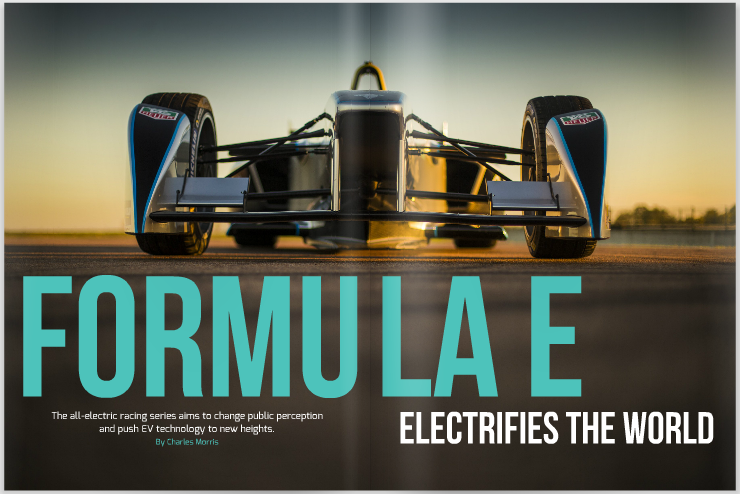

A race towards progress: The all-electric racing series

The greatest obstacle to getting more EVs on the road isn’t high upfront costs, range anxiety or a lack of infrastructure – it’s simple consumer awareness. Despite the fact that the Model S, Volt and LEAF are becoming common sights in many cities, a surprisingly high number of Average Joes and Janes are unaware that mass-market EVs are available, and few people outside of the industry understand the advantages that plug-ins have over legacy vehicles.

The most inspiring thing about attending the Miami Formula E race in March was seeing a huge crowd of ordinary folks get a thrilling look at what electric powertrains can do – that’s over 20,000 people who will have a ready rebuttal the next time they hear someone talking about “poky little golf carts.” Another 23,000 spectators saw the light at the Long Beach race in April, and tens of thousands more at the earlier races in Beijing, Putrajaya (Malaysia), Punta del Este (Uruguay) and Buenos Aires.

The FIA-sanctioned Formula E is the world’s first fully-electric racing series. The inaugural season features 10 teams, each with two drivers, racing on 10 city-center courses on four continents – Monaco, Berlin, Moscow and London are still to come. It’s an impressive diplomatic mission for electromobility.

Formula E’s mission includes not only raising public consciousness of speedy EVs, but also serving as a catalyst for manufacturers, spurring EV-related R&D and speeding the development of better and cheaper plug-in vehicles for you and I to drive. Several of the teams are sponsored by automakers or component suppliers, and others have auto OEMs as technology partners.

The master plan: from the track to the road

Technology making its way from the racetrack to production vehicles is a story as old as the automobile industry. The long list of developments that first appeared on the track includes things like disc brakes, aluminum engine blocks, direct-shift gearboxes, dual overhead camshafts, carbon fiber parts, clutchless manual transmissions, spoilers, long-lasting tires and even rear-view mirrors (which were first used by racers in the early 1910s). There is just nothing like the primal thrill of a good competition to spur creativity.

Like Tesla Motors, Formula E has a long-term plan that begins modestly, focusing on what can be accomplished with current technology, and, building on the lessons learned, passes through stages to gradually evolve into a major force for technological advancement.

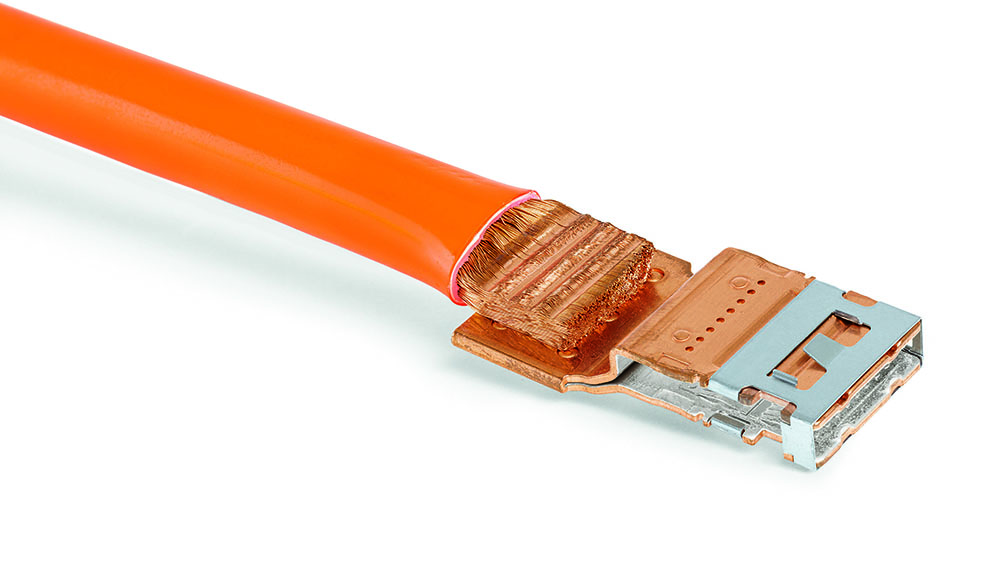

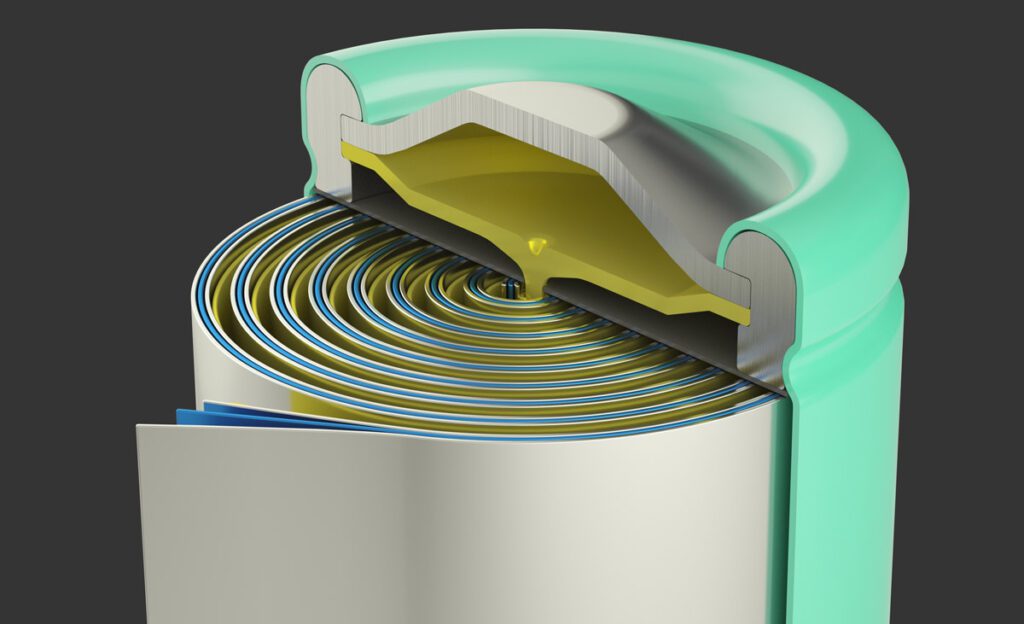

For the first season, all teams are using the same cars. In lieu of recharging, each driver performs in-race car swaps between two vehicles. Spark Racing Technology built the first-season cars, with contributions from an international consortium of suppliers. The Italian firm Dallara built the car’s carbon fiber and aluminum chassis, McLaren Electronics Systems provided the electric motor (the same as that used in the McLaren P1 supercar), Williams Advanced Engineering designed the 32 kWh (28 kWh usable) battery pack and its management system, and the British firm Hewland Engineering supplied the five-speed gearbox. 42 of the cars have been built: four for each of the ten teams and two spares.

Beginning with season two, Formula E will become an open championship, in which teams will be allowed to use their own versions of certain powertrain components, competing to develop the best electric drivetrains human ingenuity can devise. For season two, the same chassis and battery packs will be used, but teams can develop new motors, inverters, transmission, cooling systems and some parts of the suspension.

In the following seasons, Formula E plans a progressive opening of the vehicle specifications, and more and more of the electric drive systems will be open for development.

“We want this championship to be the platform where different technologies can be tested…and then they can be implemented in road cars,” Formula E Holdings CEO Alejandro Agag said recently. “One of the key elements is cost control. We want to make development gradual, and we want to make manufacturers focus on what is really important. So in season two, they will be focusing on the motor and the inverter.”

“There will be a new battery for seasons three and four. All those years, we will stay with the same chassis. Then in year five is when the big leap will happen, and then we will go from two cars to one car. Of course, this is a big challenge, in only five years to basically double the capacity or the power of those cars.”

Eight manufacturers have already announced that they will offer components for the 2015-16 season. To level the playing field between the teams that are backed by giant global automakers and those backed by smaller technology firms, an interesting rule has been issued. “One of the key elements of Formula E is this rule that other teams can raise their hand and say, ‘I would like to have your powertrain,’ and the manufacturers are obliged to sell that powertrain to any given team at a maximum capped price,” said Agag.

Sir Richard Branson, Virgin Racing team owner, said at the Miami race that bringing new manufacturers into Formula E next year will turbocharge the development of everyday EVs. “Every team next year will be working hard to beat each other and all that manpower, finance and energy will produce breakthroughs and make a big difference to normal battery-driven cars. We spend a lot of time these days looking to a world that is carbon-neutral by 2050, and unless you have sports like Formula E, we will never get there. I hope 10 years from now the smell of exhaust from cars will be a thing of the past as much as the smell of cigarettes in restaurants.”

Technology advancements

Predicting the specific type of tech advancements that may find their way from Formula E to production EVs is tricky, but talking to the pit crews in this year’s race gives us some clues. More power and less weight are the obvious benchmarks in racing, but in the EV world there is a particular emphasis on things like energy management, advanced cooling and efficiency.

“I try to make the powertrain the most powerful and efficient possible, according to regulations,” Eric Prada, an engineer in charge of performance and powertrain optimization for the Venturi Formula E team, told Charged. The same first-season vehicles were supplied to all the teams, but each team is allowed to modify the mapping of the powertrain. “We can play with the maps, and try to tune them according to what we want to get. We can play with different settings such as the electric motor torque maps and the brake regen maps. These are the two main parameters we can play with.”

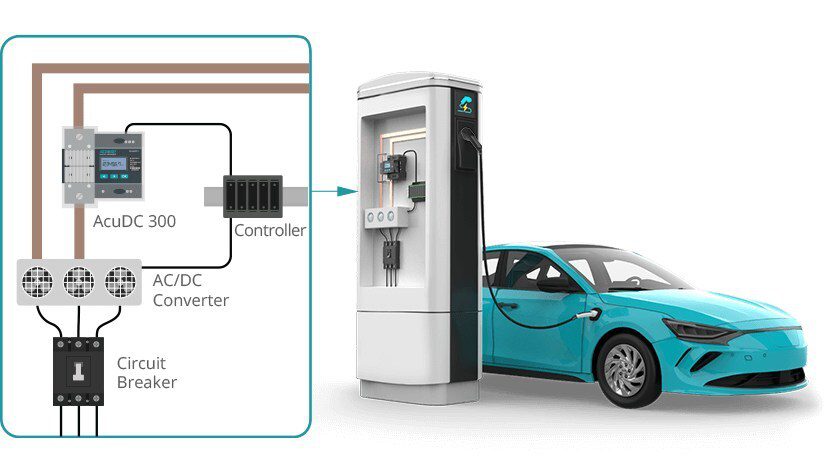

Racing requires high power levels to be sustained over long periods, and this creates some major thermal loads for the power electronics, batteries and motor. In the pits of a Formula E race, you’ll see various kinds of dry-ice-powered contraptions. They aren’t there to cool the drivers’ beer, but for the battery packs. As Prada explained to Charged, as the race goes on, battery temperature rises, and if the temperature reaches more than about 50 degrees C, power output can fall. “This is what we saw, for example, in the case of Lucas di Grassi from the ABT team, who had a problem with battery temperature [during the Miami race].” After the practices and qualifying, part of preparing the car for the race is cooling down the batteries, using those heavy-duty ice packs, especially when the weather is warm, as in Miami or Buenos Aires.

The dry-ice technique will probably not make its way into the next-generation production EVs, but other advanced approaches to dealing with cooling challenges may indeed have applications to more mundane consumer cars. Towing a trailer, for example, also requires sustaining high power levels, and can put a similar thermal burden on motors and electronics. Tesla’s upcoming Model X is the first passenger EV expected to have significant towing capability, and Green Car Reports speculated in a recent article that one of the reasons its launch has been delayed is that the company has been forced to develop better cooling technology.

In season two, Prada says that both motor and inverter will offer much potential for efficiency improvements. “There are a lot of things to do on the inverter side regarding hardware and software, for example by modifying the components inside the inverter, and trying to find clever ways to control the way you drive the motor.”

For any EV, from racecar to delivery van, the general goal is the same – to develop a powertrain that can make the most efficient possible use of the energy stored in the battery. The specific constraints are different of course, but as battery energy density is a limiting factor for EVs, the idea is always to try to optimize the efficiency of the powertrain to minimize energy losses during use.

“Compared to conventional thermal engines, which use petrol, the problem is not the same,” said Eric Prada. “For ICEs we don’t really care about efficiency, because we have a large amount of energy stored in the fuel. With batteries, energy density is limited, so we have to be really efficient and not guzzle energy.”

Venturi is one of several companies connected to Formula E teams that are doing cutting-edge EV development. The company has helped develop a range of extreme electric vehicles, including the Venturi Buckeye Bullet 2.5, in partnership with Ohio State University, which holds the world speed record for BEVs at 307 mph (see the feature article in our April 2014 issue). The company’s Antarctica is a tracked EV designed for scientific missions to use in super-cold climates (down to -50 degrees C).

A driver’s series

There are a few differences between electric racing and the old-fashioned kind. The most obvious is that, when an EV runs out of “fuel,” you can’t fill it up again in a few seconds like a gas car. Formula E deals with this issue with a simple low-tech solution: each driver has two cars, and simply switches midway through the race.

The tracks tend to be a bit shorter than a typical Formula 1 track, because speeding down a long straightaway burns up a lot of energy. The amount of equipment and crew needed is smaller than a typical Formula 1 team – the Venturi team consists of around 25 people, and each car and its related gear fits into a single shipping container.

Katherine Legge, a driver for the Amlin Aguri team, told the Fully Charged blog about some of the differences from a driver’s standpoint. The car’s weight is distributed a bit more toward the rear, because of the heavy battery pack, and there’s loads of torque, especially in the full-power map, but the biggest difference has to do with energy management. Drivers must skillfully manage regeneration, in order to avoid running out of energy too soon. The pit crew works out an optimal strategy, but once on the track it’s entirely up to the driver.

The steering wheel has a lot of buttons to fiddle with, and close communication with the support team is essential – you’ll see loads of laptops in the pits, keeping tabs on a massive feed of data from the cars at all times.

The first season, now more than half over, has seen sellout crowds enjoying some very exciting racing. The teams seem quite evenly matched – six races have been won by six different drivers. The checkered flag waved for Lucas di Grassi (Audi Sport ABT) in Beijing, Sam Bird (Virgin Racing) in Putrajaya, Sébastien Buemi (e.dams-Renault) in Punta del Este, Antonio Felix da Costa (Amlin Aguri) in Buenos Aires, Nicolas Prost (e.dams-Renault) in Miami, and in Long Beach, for Nelson Piquet (China Racing), whose father won his first Formula 1 race on the same streets almost exactly 35 years earlier.

More partners, more power

Just prior to the Miami race in March, Agag announced that two international media giants, Liberty Global and Discovery Communications had acquired minority stakes in Formula E – a major achievement that might just provide the impetus needed to convince more OEMs to come on board. “We knew we needed another partner to take it to the end,” Agag told reporters. “Really, it’s the last challenge. The beginning to now was the launch. Now we’re in orbit. We need to get to the moon still, but we’re in orbit.”

“We definitely expect more manufacturers to join from season three onwards. We are also talking with OEMs. Some teams we suspect have OEMs behind [them] but they are not revealed yet, because OEMs are cautious, OEMs want to see that the championship is there, strong, consolidated. In year two, we do have them coming to the next races, we are having this dialogue with some of the really big OEMs, and I think they will be joining us in season three.”

Agag also noted that he had spoken with Tesla CEO Elon Musk, but so far to no avail. “He says he doesn’t want to go racing. We hope to make him change his mind down the road. I think what he’s doing is amazing. We want to do what he’s done – change the perception of electric cars for people.”

This article originally appeared in Charged Issue 18 – March/April 2015.