Seth Fletcher, in the epilogue to his book about the burgeoning lithium economy, asks: “Will this last? Is this…the beginning of something enduring – a new era for transportation, energy and American high tech manufacturing? Or will it turn out to be a portrait of another false start, an anomalous couple of years in which, once again, scientists and entrepreneurs and government attempted to seed an energy revolution, only to see those seeds die when ‘business as usual’ resumed?” He has good reason to be skeptical. Today’s world presents an excellent climate for this question.

In many ways, we live in a post-world. Post-industrial and internet revolutions, post 9-11, post-cheap oil, post-Imperial America; post-modern. Many believe that it is time to move into the post-internal combustion engine era.

Some, such as battery industry advocate James Greenburger, look at it as a matter of national security – a familiar buzzword in this age of live nude body scans at the airport courtesy of the TSA. Others hold onto the promise inherent in the aims of the Environmental Protection Agency, and the hope that the end of fossil-fueled transportation will lead to breathable air, drinkable water, and quieter neighborhoods.

The story of the electric car has been one of over a century’s worth of heroic endeavors, brilliant mistakes, cult-like devotion, false starts, missed opportunities, and borderline criminal irresponsibility (and that’s just General Motor’s EV-1). It is a story that Fletcher documents with the pacing of a fine whodunit. Like the best mystery stories, Fletcher leaves the reader guessing right up to the end.

The electric car is not new. In fact, during the turn of the previous century, such luminaries as Thomas Edison felt that electricity was to be the preferred method of propelling the automobile. Then, as now, the standard methods of transportation were facing a crisis.

America was urbanizing. The horse, and buggy, had become more than just quaint relics of a bygone era: waste matter from the horse threatened to drown major cities in rivers of manure. In a society where the railroad transferred goods and people from one end of the continent to the other in record time; where the telegraph and the telephone promised to do the same for information and the human voice; where Muybridge and others were gaining mastery over the illusion of motion via the zoetrope and the motion picture; where gravity itself was becoming less and less of a hindrance to human’s ability to fly; many looked to the electric car as the personal transport solution.

The reasons were not that difficult to see. It was smooth, quiet, clean, possessing many of the qualities that draw fans and adherents today. It also was seen as slow, limited in range, difficult to recharge, and somehow effeminate, which, oddly enough, are the flaws pointed out by today’s detractors.

The gas-powered engine won out, as we know, but as Seth Fletcher points out, the victory was by no means swift nor assured.

In Bottled Lightning, Fletcher, a senior editor for Popular Science, tells the story of the people who sought to address the electric car’s perceived faults. From the drive to develop a stable, quick charging and powerful battery, to the visionaries, dreamers, madmen and crackpots that populate the history of the electric car like an engineer’s version of Days Of Our Lives, Fletcher handles his subject matter deftly.

There are truly amusing bits about super conductors designed to work at very high temperatures. Batteries that exploded, not because they couldn’t properly hold or discharge electricity, but because no one thought to test how they would respond to being charged, slowly, over and over again. Esoteric physics and chemistry that play out like middle-school locker room hi jinx. Greed, money, sex, and murder. Well, maybe not so much on the murder or sex, but you get the picture.

Bottled Lightning also addresses many of the current doomsday scenarists’ pet theories as to why the electric car, and the concurrent lithium economy, would be doomed.

A recurring theme has been the concern that dependence on foreign oil could simply be traded for dependence on foreign lithium. According to one William Tahil, energy analyst, lithium is every bit as scarce, or even more so, than petroleum. We could quickly find ourselves ceding our autonomy to China and Bolivia, countries that appear to have the lion’s share of readily obtainable lithium reserves. Chapter Nine, “The Prospectors,” has some truly fascinating insight into the debate between Tahil and geologist R. Keith Evans.

In Chapter four and five, “Reviving the Electric Car” and “The Blank Spot at the Heart of the Car,” Fletcher recounts the tale of General Motors’ EV-1. Their supposedly nefarious schemes to kill anything that smacks of oil independence gets a hearing as well.

The unveiling of the Chevrolet Volt is an interesting tale—Fletcher not only interviews GM insiders and policy wonks like Volt project head Bob Lutz and CEO Rick Waggoner, but also Who Killed The Electric Car star Chelsea Sexton as well as the team behind the Tesla Roadster.

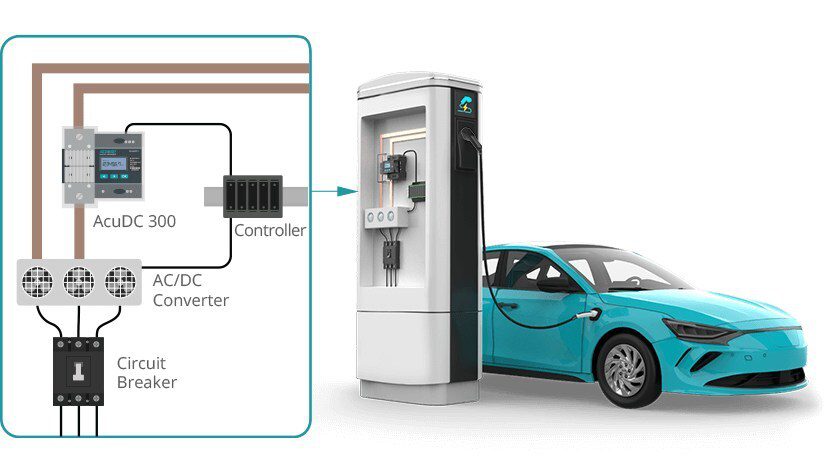

Another noted concern is the ability of our current power grid to withstand an influx of electric cars the size of our current petroleum powered fleet, charging overnight, and the infrastructure needed to handle such volume.

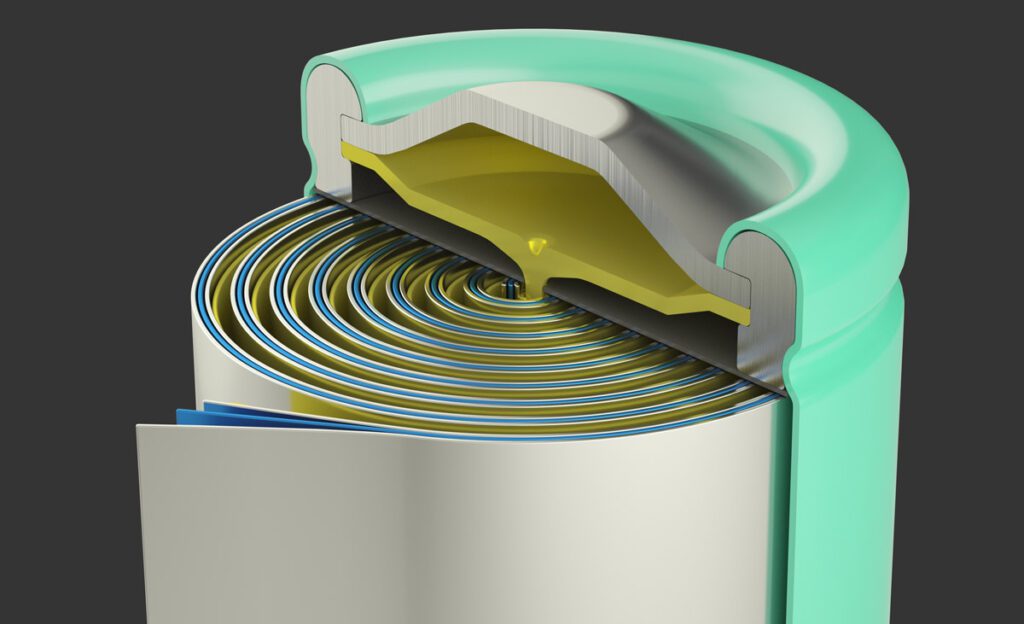

While being no techno-triumphalist, Fletcher points out the ways that scientists and engineers are seeking to move beyond our traditional views of what a battery can do, so-called far horizon projects that look at methods of increasing grid performance, and truly exotic materials science such as lithium-air batteries and paper/cloth electric storage cells.

Extensive appendices and notes make for handy reference and provide suggestions for further reading from the experts. Bottled Lightning is well written and informative. This book is a must-read for anyone who is interested in where we’re going in the field of, well, where we’re going. Recommended.

Bottled Lightning

Bottled Lightning

By Seth Fletcher

Hill & Wang, 260 pages