It’s safe to say that car dealers aren’t a particularly beloved bunch. Shopping for a car may not be as bad as going to the dentist, but for many people, it’s right up there. Technically-minded buyers find it frustrating to try to glean some factual information from the typical rambling sales pitch, while more gentle souls hate the haggling and the high-pressure hard sell.

EV boosters have another reason to vilify ol’ Cal Worthington and his colleagues. Many dealers are woefully ignorant about plug-in vehicles, and some actively discourage customers from going electric, talking up legacy ICE models with seemingly similar features and admittedly far lower sticker prices.

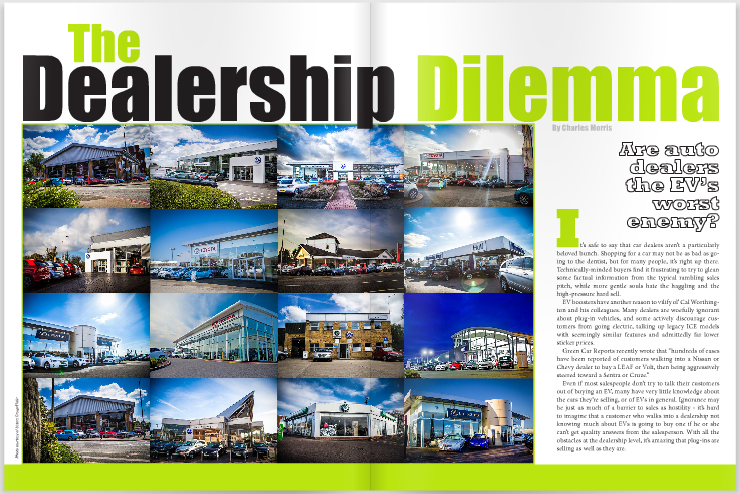

Green Car Reports recently wrote that “hundreds of cases have been reported of customers walking into a Nissan or Chevy dealer to buy a LEAF or Volt, then being aggressively steered toward a Sentra or Cruze.”

Even if most salespeople don’t try to talk their customers out of buying an EV, many have very little knowledge about the cars they’re selling, or of EVs in general. Ignorance may be just as much of a barrier to sales as hostility – it’s hard to imagine that a customer who walks into a dealership not knowing much about EVs is going to buy one if he or she can’t get quality answers from the salesperson. With all the obstacles at the dealership level, it’s amazing that plug-ins are selling as well as they are.

Plug-in vehicles are relatively complicated to understand, and misinformation is rampant in the media. Unfortunately, the OEMs’ efforts to educate their dealers are falling short, and we’re convinced that’s the real reason for the problem – not a Luddite conspiracy, but a lack of proper training.

The one company that sells only EVs, Tesla, wants nothing to do with the traditional dealership model, for reasons that Elon Musk has eloquently expressed: “Existing franchise dealers have a fundamental conflict of interest between selling gasoline cars, which constitute the vast majority of their business, and selling the new technology of electric cars. It is impossible for them to explain the advantages of going electric without simultaneously undermining their traditional business. This would leave the electric car without a fair opportunity to make its case to an unfamiliar public.”

Tesla sells its cars directly to consumers, which has led to all-out war with the powerful auto dealers’ trade groups. In many states, the law requires cars to be sold through third-party dealers, a business model that many, including politicos on both sides of the aisle, see as outdated. The battle is proceeding on a state-by-state basis, and, while recent compromises in New York and Pennsylvania are hopeful signs, any final settlement is probably years away.

One of the dealer groups’ main arguments against direct sales is the importance of warranty work. The National Automobile Dealers Association’s annual NADA Data report, released in May, emphasized warranty repairs, saying, “Warranty work performed by new-car dealers totaled $14.4 billion in service and parts last year – all at no cost to the customer.”

However, Automotive News reports that warranty work makes up only a sixth of dealers’ overall service and parts revenue, and warranty work is on the decline. As many in the EV press have noted, the dealers’ real fear is probably that, if Tesla gets away with selling directly to consumers, other OEMs, perhaps including Chinese automakers, will wish to do the same, and auto dealers will eventually go the way of travel agencies and record stores.

Some EV pundits see repairs as a reason for dealers to steer customers away from plug-ins. After all, EVs require far less maintenance than legacy vehicles, so dealers don’t want to kill the internal combustion goose that lays all that lovely warranty work down the road. However, this seems a bit far-fetched at this point. The day that EVs are so common that they put a dent in the auto repair industry is decades away and, if the majority of dealers are as ill-educated about EVs as some have proven to be, it’s likely that most of them don’t even realize that EVs need fewer repairs.

Spirited debate

At the recent EDTA Conference, Charged attended a panel discussion about the issue. What we heard was not terribly encouraging.

Dirk Spiers, the Director of battery life-cycle management firm ATC New Technologies, said that while there are a number of reasons people don’t buy EVs – high prices, lack of choices, range anxiety – “All those things are [gradually] being addressed. The real problem is the dealer, because they are reluctant to get behind EVs. They have no knowledge. They are resisting it. Fixing the dealer problem is as important as all those other issues.”

Spiers noted that, when Apple decided to take over the retail sale of its products, there was a lot of skepticism, but now Apple stores are highly successful, and the company enjoys complete control of the marketing and service of its products. The battle continues with Tesla, which is clearly following in Apple’s footsteps.

Spiers concedes that there are some very good dealers, especially in EV-savvy states such as California and Oregon. Elsewhere, however, he has found ignorance and apathy to be the rule. Spiers personally went to a number of Volt dealers, and sent friends and family to others. Among the discouraging findings: “None of us ever drove a Volt at a dealership with a fully-charged battery.” These dealers don’t seem to realize that the whole point of a plug-in vehicle is plugging it in.

Spiers also recounted the story of a friend who recently bought a LEAF, despite the best efforts of the dealer, who “tried everything to sell them an Altima, even saying that the LEAF only has 40 miles of range.” In fact, the LEAF’s EPA-certified range is 75 miles.

Spiers firmly believes that EVs are better than ICE vehicles – manufacturers just need to get the word out. He notes that EV buyers are passionate, and often encourage others to look into going electric. “Somehow we have to harness this passion to do something with these dealers. We need to explain that this is a different consumer model. We are brought up with low upfront cost and high maintenance fees. You see it with razors and blades, you see it with mobile phones, with printers and cartridges. With EVs, it’s the other way around. The vehicle is fairly expensive, but afterwards, your costs are maybe 50 cents a day.”

“For dealers, it’s innovate or die,” said Spiers. He envisions dealers becoming solution providers, as computer makers are doing, perhaps selling related products such as solar panels and energy storage. Most important, OEMs need to have an ongoing dialog with their dealers, and not just at product launch. “Engage and educate. Give them the tools, give them the information. And harness those customer satisfaction ratings.”

Disturbing data

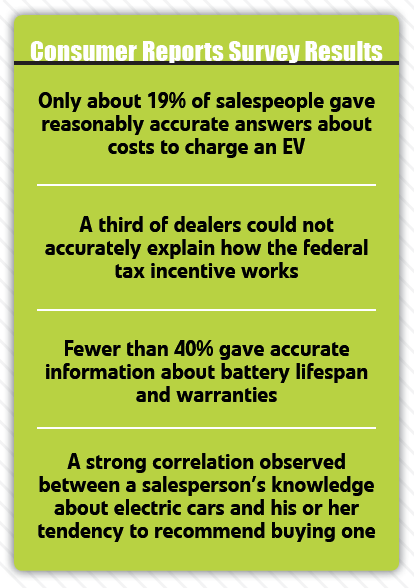

Another participant in the EDTA panel was Eric Everett, Senior Associate Automobile Editor at Consumer Reports (CR). Earlier this year, the respected consumer advocate conducted its own research on the issue. CR sent 19 secret shoppers to 85 dealerships in four states, and they asked a number of specific questions about the vehicles to test the salespeople’s knowledge. The results were disappointing, to say the least.

When asked how much it would cost to charge an EV, only about 19 percent of salespeople gave reasonably accurate answers. Some responses were bizarre – one dealer said that it would cost “ten times as much to charge at 120 volts as at 240.” One Honda dealer said no one had ever asked that question.

A third of dealers could not accurately explain how the federal tax incentive works.

Fewer than 40 percent gave accurate information about battery lifespan and warranties. Most EV batteries are warranted for 8 years or 80,000 miles, but few dealers seemed to know that. One Toyota salesman said that the Prius Plug-in required a battery replacement “every couple of years.” On the other hand, many salespeople were not aware that batteries degrade over time – one even said that range would increase as the battery got older.

CR found that selections tended to be poor – the vast majority of dealers had no more than three EVs to choose from. Why? Oddly, some said consumers weren’t interested, while others said that EVs sold out as quickly as they could get them.

CR’s team found a strong correlation between a salesperson’s knowledge about electric cars and his or her tendency to recommend buying one. They found that salespeople at Chevrolet, Ford and Nissan dealerships tended to be better informed than those at Honda and Toyota. This is unsurprising, as Ford, GM and Nissan have made major investments in plug-ins, whereas Honda and Toyota have by all accounts produced compliance cars only because the California Air Resources Board forced them to, and have made little effort to market them.

CR found that Toyota salespeople were the most likely to discourage the purchase of a plug-in model – one New York salesperson refused even to show CR’s shopper a Prius Plug-in. In fact, most of the Toyota dealerships CR visited recommended buying a standard Prius hybrid instead of a Plug-in. To be fair, that may not be bad advice. CR’s testing concluded that the Plug-in offered only a small mileage advantage over the standard Prius at a large additional cost. As much as we e-vangelists may hate to admit it, not every EV is a good buy for every customer.

Credit where it’s due

Representing the automakers’ side of the story on the EDTA panel was Robert Healey, BMW of North America’s Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Manager. As he took the podium, he joked that he was feeling “depressed” after hearing so many negative stories about auto dealers. His presentation made it clear that BMW has at least made a serious effort to prepare its dealers to sell EVs (the i3 was not yet on sale at the time of CR’s survey, so we don’t know how BMW dealers would have stacked up).

BMW has taken a step-by-step approach to electrification. The company leased its Mini-E, then its ActiveE, to large groups of drivers around the world and solicited their feedback, so by the time it launched the i3, it presumably had a substantial amount of data about customers’ concerns.

Rather than launch the i3 in selected geographic markets, BMW gave all its dealers the option of selling the new EV. Those that sign on must commit to installing charging stations and other necessary equipment, as well as training programs for both service personnel and sales staff.

Service training was “a bit more intensive” than what BMW would require for an ordinary new model. Technicians were required to complete nine modules of training, including “an in-depth dive into high-voltage battery repair.”

Sales staff are supposed to go through a full day of classroom instruction, followed by a day driving the i3 and learning its features. There is also training for staff in the Finance and Insurance department, to bring them up to speed on the intricacies of federal tax incentives, the implications for leasing, etc.

Perhaps more than any other EV maker (except Tesla), BMW sees an EV purchase as part of a new lifestyle. Through its 360 Electric program, BMW tries to assess each customer’s individual situation, and make sure that his or her needs are met. The company partners with Bosch to install home chargers, with ChargePoint for public charging, and with SolarCity to install solar panels. As a last-ditch defense against range anxiety, BMW even offers loaner gas vehicles for i3 buyers, for those times when they need to make long road trips.

Healey admits that some dealers are more committed to the i concept than others. “20 percent of our dealers will embrace electromobility…and want to sell you this car. 80 percent are reactive, they’re not proactive.”

David Noland of Green Car Reports must have visited one of Healey’s 80 percent. The salesman who showed him an i3 said that he had never driven it, and hadn’t received any training specific to the i3. He also threw out the ridiculous idea that the efficiency of the i3’s electric motor would improve once it was broken in.

Noland also wrote that one Canadian BMW dealer was so desperate for i3 knowledge that it hired the well-known EV blogger Tom Moloughney to fly to Toronto and brief his salesmen. If that’s what it takes to get dealers educated, then we’d be happy to help out too. But, one way or another, OEMs need to get serious about the dealership issues if they expect to sell the plug-in cars that they’ve invested so much to develop.

A nuanced new auto industry

It’s always tempting to see some sort of anti-electric conspiracy, but it seems unlikely that most managers are explicitly instructing salespeople to steer people away from EVs. After all, many dealerships opt in to having EVs on their lots in the first place (of course, others also opt out).

The plug-in vehicle world is extremely nuanced, and education is clearly at the heart of this problem. Try explaining to a novice the technical differences between a BMW i3 REx, Chevrolet Volt and Toyota Prius Plug-in. All three have a plug and a gas tank, but also differ in significant ways.

On top of the many different electrification configurations, add a variety of recharge times, power levels and plug standards, and it’s easy see that inexperienced sales staff will need intense training sessions to really understand all the ins and outs of the plug-in scene.

Salespeople’s reluctance to sell EVs is partly due to plain old resistance to new ideas, but the main reason is a serious lack of knowledge. That needs to change, and the OEMs are the only ones who can change it.

Top image courtesy of Listers Group/Flickr

This article originally appeared in Charged Issue 14 – June/July 2014