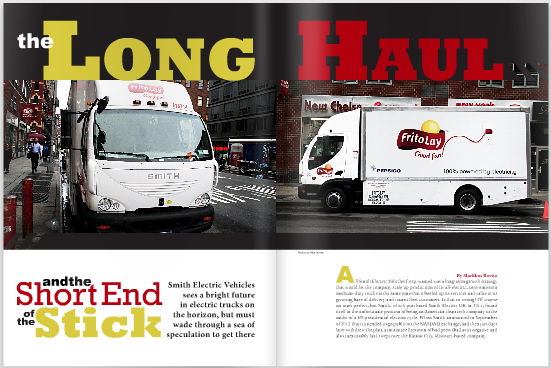

Smith sees a bright future in electric trucks on the horizon, but must wade through a sea of speculation to get there.

All Smith Electric Vehicles Corp. wanted was a long-term growth strategy that would let the company scale up production of its all-electric, zero-emission medium-duty trucks at the same time that it beefed up its services and value to its growing base of delivery and transit fleet customers. Is that so wrong?

Of course no one’s perfect, but Smith, which purchased Smith Electric UK in 2011, found itself in the unfortunate position of being an American clean tech company in the midst of a US presidential election cycle. When Smith announced in September of 2012 that it intended to go public on the NASDAQ exchange, and then just days later withdrew the plan, a miniature firestorm of bad press (bad as in negative and also inexcusably lax) swept over the Kansas City, Missouri-based company.

Rumors of Smith’s impending bankruptcy flitted about the pages, websites, and TV sets of certain media outlets, where slightly sloppy comparisons of Smith to Solyndra hardly concealed the hackneyed attempts to associate struggling clean tech companies with a failure for the Obama administration, whose Department of Energy had supported them. It was the same old story we’ve heard at various stages about Tesla, Fisker, A123, the Chevy Volt, and others. The clean tech sector and EV industry in particular was being used as a backdrop to paint the DOE’s stimulus grants and guaranteed loans for such companies as a failure of government meddling with free enterprise. Could this unrelenting correlation, whether deserved or not, actually do more harm to the EV industry than the administration’s supportive policies could help?

Rumors of Smith’s impending bankruptcy flitted about the pages, websites, and TV sets of certain media outlets, where slightly sloppy comparisons of Smith to Solyndra hardly concealed the hackneyed attempts to associate struggling clean tech companies with a failure for the Obama administration, whose Department of Energy had supported them. It was the same old story we’ve heard at various stages about Tesla, Fisker, A123, the Chevy Volt, and others. The clean tech sector and EV industry in particular was being used as a backdrop to paint the DOE’s stimulus grants and guaranteed loans for such companies as a failure of government meddling with free enterprise. Could this unrelenting correlation, whether deserved or not, actually do more harm to the EV industry than the administration’s supportive policies could help?

Meanwhile, the seemingly eternal election campaign mercifully ended, and Smith had moved on to the important work of scaling up its business to attain profitability.

By late November, it was making headlines again, this time for its announcement of a new factory in Chicago that would produce an estimated 100 new jobs and 1,200 electric trucks a year.

Shouting fire in a crowded theater

Among the slurry of Smith doom and gloom reports that erupted in September, was the Washington Examiner article ‘Staggering Smith Electric may be next Solyndra-like clean energy flop’ by Richard Pollock. In the midst of declaring the company all but bankrupt (and mentioning Obama six times), Pollock “reported” that Smith admits to having trucks that caught fire – a la battery explosions:

The SEC filing contained other damaging revelations. The firm said that its truck’s lithium-ion battery cells “have been observed to catch fire or vent smoke and flames,” and their warranty reserves may be insufficient to cover future warranty claims.

There is one itty-bitty problem with that: It’s not exactly what the SEC filing states. It says:

Our commercial electric vehicles make use of lithium-ion battery cells, which, if not appropriately managed and controlled, on rare occasions have been observed to catch fire or vent smoke and flames.

Here, the S-1 form is addressing the possibility of lithium-ion battery fires (notice the term “if”). Smith was informing potential investors of all future problems within the realm of possibility, the prudent (and legally required) thing to do when issuing an IPO. In the same way an S-1 filing from a startup company that produced conventional ICE vehicles should read “our cars burn gasoline, which is known to occasionally cause fires.”

Growing pains

In an interview with Bryan L. Hansel, CEO and Chairman of Smith Electric Vehicles, he told us that the IPO process, which started with the company’s first SEC filing in November, 2011, was originally an attempt to gain the capital necessary to scale up its operations from hundreds of trucks a year to thousands. If the rumors of Smith’s financial straits were actually true, then of course it would still be indicative of a CEO to paint a rosy picture even as the ship sank. But Hansel explained that because Smith was not profitable, the IPO, which sought to raise $76 million, would have come in with a company valuation that Hansel felt was too low, which would be bad for Smith’s existing investors. Instead, he hit the pavement seeking another round of private financing, with the plan of reaching profitability before revisiting a public offering.

“We made the strategic decision to stay private,” Hansel said. “A lot of companies in this space have not been in that position. If we could have gone public it was an opportunity to accelerate our access to capital and grow at a pace. So we took our shot. We got a tremendous response. Everyone loved the customer base, but ultimately as a business we were early. We were pre-profitability. I think a lot of that was less about Smith and more about clean tech, because a lot of clean tech companies have struggled getting over that line of profitability. So we’ve chosen to get over that line, and then we’ll have a lot of flexibility. In the future, because of the scale of transportation and the size of industry we’re trying to serve, I think it’ll ultimately be best if we’re public.”

While the post-IPO-withdrawal rumors of Smith’s demise now appear to have been premature at best, how does such an event really affect a company’s long-term image? “Obviously, pulling the IPO left some investors interested in the electric vehicle space scratching their heads as to what’s actually going on,” said John Licata, chief energy strategist at the Blue Phoenix research firm. Licata frequently speaks on TV and at conferences on new energy opportunities and electric mobility. “I certainly believe that Smith is very viable,” Licata continued. “Look at Facebook. How many times did Facebook say they were going public, and then they changed their mind? But Smith needs to seriously execute and deliver on the promises to potential investors and clients, because everyone’s watching. This company needs to not misstep right now, because the industry will be unforgiving if they do.”

Newtonian physics

While Smith’s IPO was shelved for now, the company did enact the first phase of its plan to scale up in 2012, which was to launch the Series 2000 of its Newton truck platform. Smith also produces the light-duty Edison truck in its Newcastle, UK facility, but the medium-duty Newton is the only platform produced in the US. This platform is a common set of chassis, rails, axles, and drive system that can be configured into a stake bed truck, school bus, step van, refrigerated box, or other applications. It has a modular lithium-ion phosphate battery pack that comes in 40, 60, 80, 100, or 120 kWh sizes, for a range of up to 150 miles per charge.

In the previous Newton iteration, Smith worked with third parties such as Enova for the drive system and Valence for the battery modules and management system. However, for the Series 2000 Newton, Smith integrated new proprietary core drive train and battery management systems so that everything runs on common communication software, as well as real-time telemetry. “Every five seconds we pull down data off of every vehicle on the road, and we can see over 1,500 operating parameters and real-time diagnose the entire vehicle,” Hansel said.

Photo by Alex Nunez

A second key advantage to the Series 2000 Newton comes by way of scalability. With the integrated design of the Series 2000 Newton, Smith can work on pushing it into a mainstream supply chain. “Up until now, in any given month, the number of units we shipped was not based on how many orders we had,” Hansel said, “it was based on how many of a given component we could get.” Hansel says Smith will now be able to deliver as many trucks as its customers want “It’s a triple benefit by migrating to more mainstream suppliers,” he says. “They give you capacity to build thousands instead of hundreds, higher quality because their processes are more mature, and they’re more cost-effective.”

With the ability to produce more trucks comes another big challenge for Smith: becoming a truly turnkey solution to its customers for the entire Newton product, which would include infrastructure, all the interactions with utilities, and full implementation of the vehicle, beyond simply its production. Up until now, such things have been left to the customer, with Smith offering vendor suggestions, as well as training for the drivers and service techs. But as Smith’s Fortune 500 customers, such as Frito Lay, FedEx, Coca-Cola, Staples, and others, think about moving from a couple of hundred electric trucks to 1,000 or more, they want Smith to take ownership of the logistics.

“We’re stepping into a new role,” Hansel said. “[Customers] had to find their own local contractors and get their charge points in place. But now they’re saying, ‘guys, this is not added overhead we’re going to become experts at.’ Most big fleet people are not facilities people. So that’s the next phase for us. If they buy a truck, it’s got to be easy. Everything’s got to be taken care of. We see that as a critical next step to allow this to go to scale.”

Chicago bearish or bullish?

Smith’s November announcement of a Chicago manufacturing facility came just about one year after a similar announcement in November, 2011 of a plant in the South Bronx of New York City. Along with Kansas City, that will be three American factories for Smith. Hansel told us the South Bronx plant is just now coming online, and the prognosis is that Chicago will be churning out Newtons by the end of the second quarter of 2013. These multiple smallish facilities fit into Hansel’s plan for Smith’s steady, but unpredictable, growth.

“Our core strategy is decentralized manufacturing assembly,” Hansel said. “We have relatively small facilities in local environments, where we can actually produce the product where there is demand. By being local we can accomplish both the up-front manufacturing as well as the long-term service and parts support of the vehicle.”

Of course, it doesn’t hurt that the announcements for both Smith’s NYC and Chicago factories coincided with announcements from local government officials of incentives programs for companies to convert commercial vehicles to electric. In New York last year, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a multi-year plan for vouchers for buyers of electric trucks worth up to $20,000 each, with $10 million committed in the first year. With the announcement of Smith’s Chicago facility, Mayor Rahm Emanuel unveiled a $15 million incentive plan for rewarding fleets that convert from diesel to electric vehicles, on a progressive scale that gives bigger incentives according to the size of the EV’s battery.

Both cities’ incentives programs are funded with CMAQ (Congestion Mitigation Air Quality) money, a federal program. Smith has never taken federal loans, but any critics looking to wag a finger at the e-truck company for having its hand out could point to the $32 million total in DOE grants that Smith and its customers have utilized since 2009 and the company’s propensity for placing factories where federal money is subsidizing electric trucks. Of course, the latter sounds like nothing if not a shrewd business decision.

“We’re economically competitive with diesel anywhere you want to put a truck,” Hansel said, “but we do see concentrations where there are incentives available. It certainly accelerates the conversation and makes the map even easier, because you are getting an incremental incentive if you go to those geographic regions. But these big national fleets can put trucks anywhere, and they’re more likely to put them where they’re going to get a financial benefit for doing so.”

Licata sees the synergy between Chicago’s new CMAQ incentives and Smith’s new plant as an excellent proving ground for Smith’s localization strategy. “I think they need to show that the opportunity they have in Chicago can work in other cities,” he said, “and use that as a template to grow their business. The proof is in the pudding. They need to show execution in Chicago. I think that will help them tremendously.”

As far as Hansel is concerned, Chicago is still only the beginning. “The beauty of our model is we can bring on manufacturing capacity in a new geographic market very quickly,” he said. “It’s inexpensive; you’re talking 90 to 120 days, and we can have additional capacity brought online in a new market. We sized our manufacturing strategy so at hundreds of vehicles we can be profitable at a location, and then we can add locations as demand grows. And quite honestly, it’s really hard to predict growth, so we have a model that gives us the flexibility to react to it. It’s kind of counterintuitive, because traditional automotive is: Build a big, huge facility, and when I cross that x number of tens of thousands of vehicles, then I start making money.”

As far as Hansel is concerned, Chicago is still only the beginning. “The beauty of our model is we can bring on manufacturing capacity in a new geographic market very quickly,” he said. “It’s inexpensive; you’re talking 90 to 120 days, and we can have additional capacity brought online in a new market. We sized our manufacturing strategy so at hundreds of vehicles we can be profitable at a location, and then we can add locations as demand grows. And quite honestly, it’s really hard to predict growth, so we have a model that gives us the flexibility to react to it. It’s kind of counterintuitive, because traditional automotive is: Build a big, huge facility, and when I cross that x number of tens of thousands of vehicles, then I start making money.”

The bottom line

“Last year I wrote a white paper about how 2012 is the year that EVs hit puberty,” Licata said. “And I think that in 2013, there’s still a growing phase we’re going to see.” Licata spoke of the entire EV industry there, but his point applies quite well to Smith’s particular situation. In 2012, Smith completed a key component to its development, which was the Series 2000 Newton truck fully integrated with Smith proprietary technology. Now in 2013, Smith focuses on turning a gross profit in the second half by reaching a mass production scale.

“Our 2013 is about profitability, and we’re going to get there,” Hansel said.

Objectively, the pieces do seem to be falling into place for Smith, as long as the financing can hold out long enough. They have a more cost-effective and higher-capacity supply chain so that each Newton sale will bring in a higher margin, new production facilities to begin to produce thousands of trucks per year, new regional customers such as Duane Reed and Fresh Direct in New York, and a proven product – there are about 700 Newtons currently on the road, which have logged millions of miles. The missing piece – thousands of new e-truck orders – shouldn’t have Hansel reaching for Ambien tablets, as he thinks the Newton practically sells itself.

“We’ve always told our customers that buying an electric truck isn’t about doing something that’s right for society,” Hansel said, “it’s about making a great business decision. Where we can declare victory is in convincing people that it’s reliable, good technology. We’re millions of miles into it. We’ve got hundreds of vehicles. We’re over that hurdle. You talk to our key customers, and there are no worries about the truck anymore. The truck works.”

“We’ve always told our customers that buying an electric truck isn’t about doing something that’s right for society,” Hansel said, “it’s about making a great business decision. Where we can declare victory is in convincing people that it’s reliable, good technology. We’re millions of miles into it. We’ve got hundreds of vehicles. We’re over that hurdle. You talk to our key customers, and there are no worries about the truck anymore. The truck works.”

Hansel believes the Newton makes sense to any fleet operator who runs the numbers. Going by a purchase price of $65,000 for a comparable ICE cab and chassis, the $75,000 Newton tacks on an up-front premium but offers maintenance savings, fuel savings, and longevity. From there, you select a battery size appropriate for the truck’s daily route. Smith suggests a 20 percent cushion to account for extra power drawn at certain times. “If you have substantially more than that,” Hansel said, “then you’re not utilizing the asset of the battery and it impacts your economics.” Other than that, if you look at the price of the battery on a six-year payment structure plus electricity, Hansel expects a month-one savings on fuel.

Just like with VIA Motors, whom we profiled last year, Smith has an advantage over boutique electric car companies in that its single-shift fleet customers fit the profile of an EV buyer: hey have predictable daily driving needs and they are motivated by lower costs. They take the time to do the math.

“If you think about a big corporate environment, and energy efficiency as an opportunity, I don’t see an electric truck as meaningfully different than LED lighting,” Hansel said. “You’ve got an asset that works today in a fluorescent light. You add LED lighting because it’s meaningfully more efficient, and over time, you’re going to save a lot of money. Our truck will save you about 80 percent operating cost every mile you drive, so you just have to look at it and decide if you want to take advantage of those efficiencies. I think most people do, because it’s doing the same job that the incumbent product does, just more efficiently. Why wouldn’t you take advantage?”

“If you think about a big corporate environment, and energy efficiency as an opportunity, I don’t see an electric truck as meaningfully different than LED lighting,” Hansel said. “You’ve got an asset that works today in a fluorescent light. You add LED lighting because it’s meaningfully more efficient, and over time, you’re going to save a lot of money. Our truck will save you about 80 percent operating cost every mile you drive, so you just have to look at it and decide if you want to take advantage of those efficiencies. I think most people do, because it’s doing the same job that the incumbent product does, just more efficiently. Why wouldn’t you take advantage?”

We’ll leave that last hypothetical question open for some other media outlet to answer.