Venture capitalists assume a large amount of risk when they invest in early-stage companies. They do so because of the potential for huge returns. To ensure that a portfolio of investments delivers the greatest return with the least risk, VCs spend a considerable amount of time evaluating companies, looking for the key ingredients of success.

In 2010, when Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers (KPCB) – one of Silicon Valley’s top VC firms – decided to invest in Proterra, it did so after exhaustive research into the market for electrified heavy-duty vehicles.

At the time, Ryan Popple was part of KPCB’s Green Growth team. Popple and fellow VC Michael Linse looked at “everything under the sun” before deciding that Proterra was in the best position to benefit from the coming wave of disruption as EV technology washes over the heavy-vehicle markets.

If anyone is qualified to evaluate early-stage EV companies, it’s Popple. At KPCB, Ryan led nine transportation investments and served on ChargePoint’s board. And prior to KPCB, he was an early employee of Tesla Motors, where he served as Senior Director of Finance. At Tesla his role was to focus on strategic planning, technology cost reduction and corporate finance. During his tenure, the company scaled from pre-revenues to over $100 million in vehicle revenue, reached profitability and achieved an IPO filing. Coincidentally, that skillset is just what Proterra needed for its next stage of growth, and last year he signed on to lead the company as CEO.

Charged recently caught up with Popple to get his take on the economics of the electric bus market.

Charged: What led to you to originally invest in Proterra in 2012?

Ryan Popple: It was a natural technology for me to explore at Kleiner Perkins, since I’d come off of three years of early and mid-stage growth at Tesla. I knew the electric vehicle powertrain stuff pretty well.

It’s a pretty straightforward thesis, that an electric drivetrain is a really great fit for urban transit. That’s anywhere you’re moving a lot of human beings in a stop-start, high-utilization urban environment – municipal, delivery, commercial, theme parks, universities, private transit fleets, etc. We looked at a lot of different truck and delivery companies, basically all the companies that were thinking about doing electrification. In the end, we were very interested in Proterra for a number of reasons that were largely related to its core product strategy in addition to other aspects of the company.

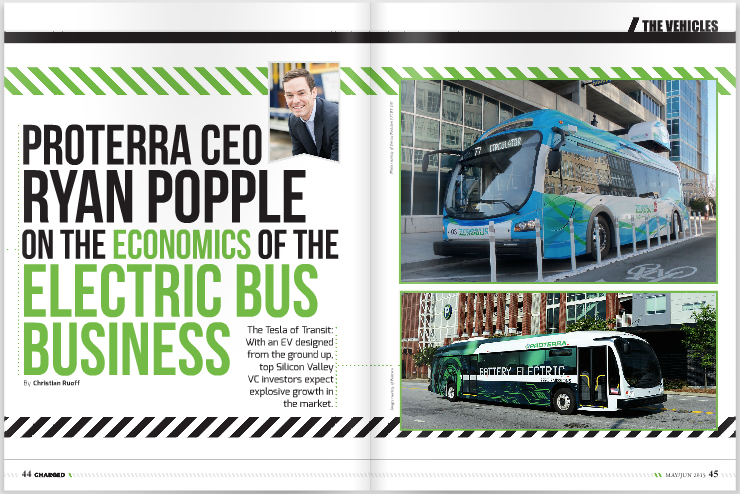

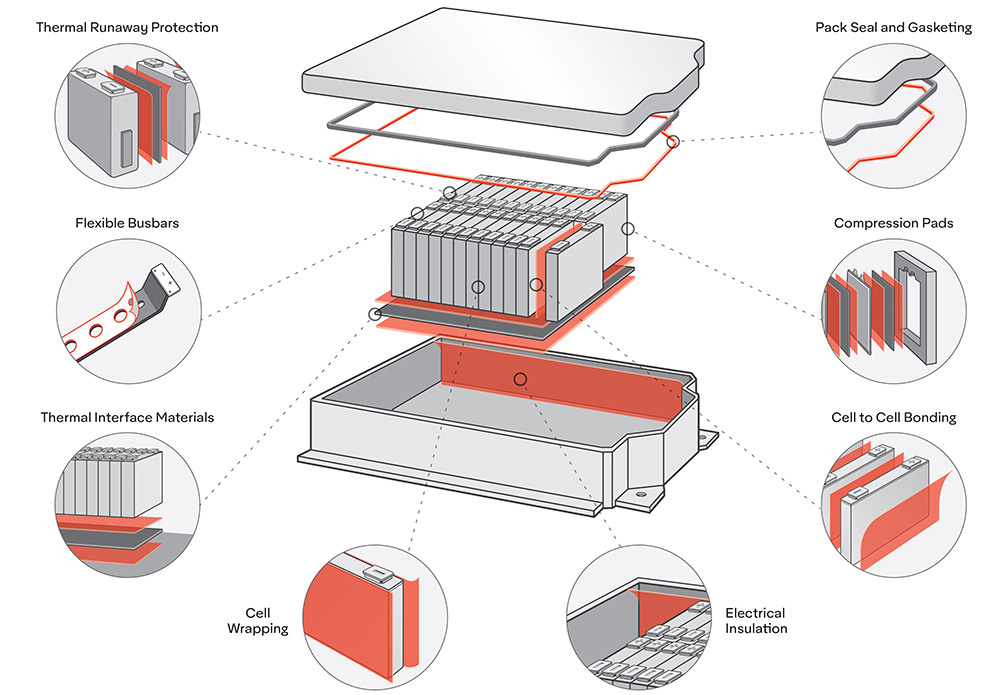

Proterra is not the only company that thinks EVs make a lot of sense in urban transit, but it is the only company that did a purpose-built EV. On the surface our vehicles could seem similar to some other attempts at heavy-duty EVs, but if you dig into the company’s approach, it is very different. From the composite body to all of the components, our EV buses are designed and built from the ground up. We’re focused on building high-performance EV mass transit buses, so we don’t do conversions, and don’t have any unnecessary or legacy parts from a combustion vehicle. We have the largest engineering team focused on EV product development in the North American transit bus market, and as a result have designed an EV drivetrain with the best efficiency ever for a 40-foot transit bus, 1.7 kWh per mile, which is equivalent to 22 MPGe. We also design our own battery packs using modules from multiple lithium-ion suppliers worldwide, and are benefiting from the high-level of competition, driving costs down. Ultimately, everything has been optimized to be an EV.

Charged: Companies that VCs invest in are typically expected to have explosive growth potential. Could you give us an idea of where you are on that curve, and your estimation of the size of the market?

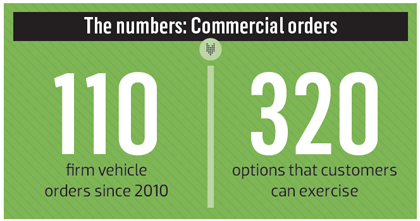

RP: Proterra started out as a classic technology startup. Dale Hill founded the company in 2004 after working on a hybrid electric technology for transit. He had the idea that the company could build a battery-dominant vehicle, instead of a hybrid, so the company spent several years in engineering and R&D before it won its first commercial orders in 2010. Since then we’ve booked 110 firm orders, including 320 options that customers can exercise if they choose to. In total, we’re currently contracted for over 400 vehicle orders, we’re in over a dozen cities and have logged over one million miles of regular service.

Whether you’re buying an electric or a diesel bus, these infrastructure-grade vehicles are a 10-12 year investment. It only takes about 10 to 20 cities to commit its fleet for a company like Proterra to be over $100 million of annual revenue and profitable. Once we’re in that ballpark, we’ll start looking at becoming a public company. Currently, we’re producing vehicles at a good clip, and every time we ship a bus, we get paid for a pretty high-price piece of technology. We were cash-flow positive in Q4 2014, and cash-flow positive this April, simply because we delivered a decent-size order for Nashville, Tennessee. I think we need to double one more time in terms of our top-line revenue, and we will be profitable.

We’ve seen our pipeline – or actionable opportunities that we’re going after – grow about five to seven times in the last year alone, so we’re seeing demand swiftly increase, and we’re only focused on the North American market right now. Twelve to fifteen months ago, if you added up the value of the opportunities that we were talking to customers about, it would probably be somewhere around $100 million – that’s the value if we had booked every possible order that we were discussing with potential customers. It was a good start, but today we’re closing in on $1 billion of total pipeline opportunities. Of course, we won’t book orders anywhere near that, because there is a large range of probability when it comes to converting discussions into sales. For example, if it’s an initial conversation and we’re still educating someone about batteries, electric motors and inverters, you put that conversation way down in the single-digit percentage for the likelihood of closing the sale. If it’s a conversation about a follow-on order from an existing customer, that’s a pretty high value. What’s promising is that we’re in contention for roughly 20% of the potential transit vehicle orders in the US over the next couple years. Again, we won’t win all of that business, but if you talk to transit managers right now, there’s a decent percentage that think EVs are the long-term future of the market.

The internal conversations we’re having now are about planning capacity appropriately. As a hardware company, it’s important to scale production to be able to credibly address potential orders and growth, and that’s what we’ve done with our second production facility in California. This additional facility will be ready to meet the customer demand we’re experiencing on the West Coast, and our Greenville facility will support orders east of the Mississippi. Balancing investment with customer orders is fundamental to avoid underutilizing capital. Once we passed a one-year backlog in orders, we knew that we needed to increase capacity; otherwise we would start seeing demand destruction. For example, a transit agency recently visited us and wanted to know if they placed an order today, when would the vehicles be delivered? Right now the first open build slots that we have for the Greenville facility are in the second quarter of 2016. Overall, we like having about a year of backlog in the system, because it makes it much easier in terms of supply chain management and inventory planning. But we don’t want more than that.

The California site will most likely go into production in the first quarter of 2016. That facility’s initial capacity will be about 50 buses per year, with enough headroom to scale production to about 200. We’ve already started taking orders against that capacity and are expecting the new facility to fill up pretty quickly. The first order that we’ve publicly announced is for Foothill Transit, which has placed its largest order to date with us for our new extended-range vehicle, the Catalyst XR. The additional 13 Proterra buses will bring Foothill Transit’s all-electric fleet to nearly 10 percent of the agency’s total.

Charged: That kind of growth implies that you offer an attractive financial model to your customers. How do the costs compare to hybrid, diesel and CNG buses?

RP: In fact, most of our conversations are about the economics of going electric. We had a customer recently from a medium-size city in the southeastern US. You would not expect that this city would be an early adopter of green tech, and it highlights that for most cities it’s about the total cost of ownership (TCO), managing pricing risk of fuel and reducing maintenance costs.

Every case is different, but if you took the average transit agency in the US and deployed a Proterra vehicle against a diesel vehicle, you would see a TCO for a Proterra vehicle of about $1 million for a lifetime of operation, versus about $1.4 million for a diesel bus. That includes the upfront acquisition cost, midlife maintenance, and the fuel (electricity or diesel) it will consume.

In terms of upfront costs, a diesel bus is somewhere in the ballpark of $400,000 to $450,000. A CNG bus is around $500,000 to $600,000, depending on configuration. And diesel-battery hybrids are somewhere from $650,000 all the way up to $730,000.

Our prices depend on the battery configuration. You can buy the vehicle and lease the batteries for somewhere in the neighborhood of $550,000. If you want to buy the batteries and own them outright, and you want the maximum battery configuration, you’re looking at something around $800,000. Most of the options that we’ve been pricing this year, and getting a lot of traction with, are in the $700,000 range. That compares very nicely against hybrids, and a hybrid only gets 5 MPG, versus 20 to 25 MPGe for our EVs.

I think that maintenance piece is what’s going to take EVs from being an exciting early adopter category to the dominant technology in transit. I say that because the biggest headache everyone has is keeping their vehicles running. I visit transit agencies that have job shops in their maintenance bays that are doing nothing but transmission and engine rebuilds for traditional buses.

We often talk to our customers about going from analog to digital. Diesel and natural gas buses are inherently complex – a lot of skilled labor goes into to keeping them on the road. Our vehicles are clean, quiet and simple. There are far less moving parts in any EV versus an ICE.

So, we’re already pricing very close on a first-cost basis to diesel-hybrid. From a bill of material perspective, I think we’re already cheaper, because hybrids basically have a battery-electric drivetrain and a heavy diesel drivetrain. That’s an easy technology for us to go after. Then, CNG powertrains are the next most expensive. And the big advantage we have over CNG is that the infrastructure is a nightmare. They are million-dollar fueling stations, and CNG has the tendency to react very poorly with fire or sparks. So it’s easy to see that electricity is a much more reasonable and cheaper approach if you haven’t already deployed CNG.

And the last one, and the cheapest one, on a first-cost basis, is the plain old dirty diesel bus.

I would say the biggest competition we have is the wait-and-see or do-nothing attitude. We are in a dozen cities now. We’ll be in 18 in six to nine months, and two dozen by the end of next year. But there are 500 US cities that we’re targeting. That’s just US public transit, before the global markets, school buses, etc. We’re thrilled to announce some of our newer larger orders, but the reason we’re in this business is that there are 70,000 diesel buses in the US, and they are some of the most polluting vehicles in the most emissions-sensitive urban areas.

The average diesel bus consumes 10,000 gallons, and CNG is around 12,000 gallons a year, with a host of emissions. These vehicles also stay in service for 10-12 years, so we’re focused on speaking with transit managers before they sign a purchase order for 100 diesel buses.

Charged: Are most of your sales paid for by special initiative funding or are they out of the standard operating budget for a city or transit authority?

RP: Definitely early on grant funding was important, but we’ve been able to reduce technology costs by $500,000, and now it’s possible to not rely on any sort of special funding at all. A big focus of Proterra over the past two years has been to move out of special grant-funded programs and into normal procurement, but it’s still a mix. Some of our customers have seen grant funding from the Federal Transit Administration and state or city programs, and other customers have started relying completely on what we would consider normal operating budgets or local funding.

We’re also moving into the commercial transit sector and have received a lot of interest from universities, theme parks, airports, Fortune 500 fleets, etc. It’s a compelling business case for private sector owners.

Charged: What sort of regular maintenance is expected on the electric drivetrain over a vehicle’s life?

RP: We tell our customers to assume that at midlife, or some point within 12 years, we’re going to need to do some work on the battery pack to bring it back up above 80% of the original capacity. The good news is that our oldest vehicles have been in Southern California since 2010 and we’re seeing a lighter degradation curve than we forecasted for the customer. So it’s possible that in some cases we won’t need to touch the batteries at all. However, we make a commitment to our customers to maintain 80% capacity and, worst-case scenario, if we needed to give them a new battery pack at year six, we’ve actually planned for that in our cost structure. The nice thing is that battery costs are coming down every year and the reserve that we set aside for this exceeds the need. Also, a lot of our customers are very conservative with the amount of energy storage they put in their vehicles. That means the depth-of-discharge is lower and they can get all the way to year 12 with over 80% capacity.

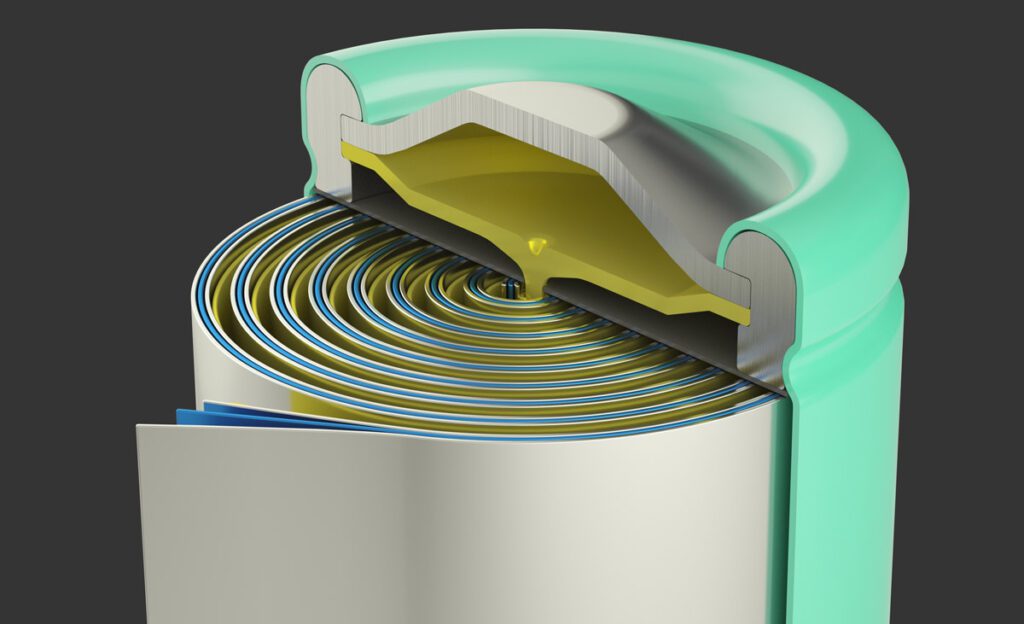

We use the most durable Li-ion chemistry you can get your hands on, in the form of lithium titanate oxide (LTO). We also use higher energy density chemistry for the long-range vehicle configurations. There is no chemistry that can cycle as many times as LTO. It can cycle 20-40,000 times before you hit 80% of the original capacity. But even with the very robust cells from Toshiba, we are very conservative, because in the early adopter market you don’t want to over-promise and under-deliver, especially when it comes to batteries. And there are a lot of ways we refurbish the capacity more efficiently than just providing brand-new packs. We perform a rebalance at the module level, and don’t actually go into the cells within the modules.

Charged: How many design iterations have Proterra’s buses gone through?

RP: From a platform architecture level, I’d say we’re on generation two. In a lot of ways, our generation-one fleet reminds me of the Tesla Roadster in that the purpose was to get into market and burn as little capital as possible. The idea was to get something into our customers’ hands so they could teach us everything we didn’t know about serving the market with a new technology. But then you get to a point, just like Tesla got to with the Roadster, where you need to make a discontinuous change in the platform and go deeper with the engineering.

The biggest thing you’ll notice is that we went from a 60-passenger 35-foot vehicle to a 77-passenger 40-foot vehicle, while dropping over 1,500 pounds of weight. We learned a lot about the structural engineering of a composite vehicle. The energy density of the battery packs also went up quite a bit, so we’re putting a lot more energy into a much smaller package.

So, our second-generation bus platform started as an independent engineering project over two years ago, taking in early adopter feedback. We’ve invested roughly 40-50 million dollars of internal and external R&D on the program, and we’ve made a series of changes throughout. In the end, the new Catalyst platform is focused on the ability to scale the technology into large fleets, and we’ve been able to significantly drop the costs of the buses.

Charged: What kind of variation in charging options do you offer customers?

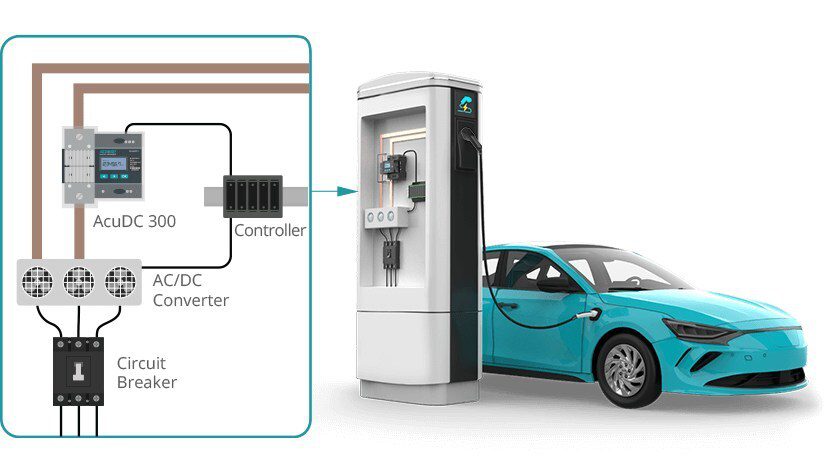

RP: We see two charging models that make a lot of sense, and we’ve developed technology, or partnered with other companies like Eaton, to be able to deliver it. Currently, all of our customers at some point in their operation have at least one fast charger. The method of fast charging that we recommend is overhead fast charging. In this case, the vehicle drives into the bus stop or the bus yard and enters the hot spot of the charging zone. Then our software takes over and slows the vehicle down. Drivers can steer left or right, but they can’t drive through a charging stop too quickly, and they also can’t drive away while it’s actively charging. We like overhead charging because we’re dealing with pretty high power levels – some customers charge as high as 500 kW – and that would require very heavy-duty cables to plug in, and possibly cause interference with loading or unloading the vehicle. In some cases customers put overhead fast chargers along the bus routes, and in other cases they’re at the transit centers.

Almost all of our customers also use conventional plug-in overnight chargers. So, the two models that we think are going to dominate are plug-in overnight charging and then the occasional overhead fast charging to double, or triple, the effective range of the vehicle.

We’ve done some pilots and studied things like wireless charging, but the challenge we see is that as the batteries are improving, the need for en route charging keeps getting smaller. So it ends up being cheaper to just put a little bit of extra range on the vehicle. The other complexity is that we’ve yet to see truly repeatable, high-efficiency transfers for wireless. In our market, when you’re using this much power, you really care about every percentage point of transfer efficiency.

Charged: What’s the future for EV mass transit?

RP: Right now, there is a quiet EV revolution occurring across North American transit agencies, and we believe that the transit vehicle market will be the first transportation market to eliminate petroleum.

This article originally appeared in Charged Issue 19 – May/June 2015.