Any new plug-in vehicle from a maker that hasn’t previously offered one is cause for excitement, even if volumes are low at first.

So I approached my six-day test of the new plug-in Subaru Crosstrek Hybrid with anticipation. Sure, its rated 17-mile electric range is below the curve, but at least it’s a start – and with Toyota plug-in hybrid electrical components borrowed from the Prius Prime, I expect a Subaru PHEV to be a good new addition to the market.

I should note up front that I’m on my fourth Subaru, this one an Outback that will celebrate its 20th birthday this fall at the relatively modest mileage of 138,000. Moreover, Subaru’s legendarily outdoorsy, nature-focused, active-sports buyers seem a very good fit for a car that can run at least partly with zero emissions from its tailpipe.

My verdict after six days and 360 miles, covering about one-third urban and suburban errand duty and about two-thirds highway miles, was mixed.

The pros

Reassuringly, the Crosstrek Hybrid remains every bit a Subaru. The hybrid variant shares all the Crosstrek’s appeal, as the sole compact hatchback that comes standard with all-wheel drive. And it delivered the brand’s legendary and reassuring traction on my steep, wet, muddy, uphill drive and a few other locations where traction was crucial.

But as the name signals, if you evaluate the car purely as a hybrid, it does well. It’s rated at 35 mpg combined (versus 29 mpg for the standard Crosstrek with continuously variable transmission) and I saw 38.1 mpg on the trip computer over my time with the car. (I didn’t have enough time to test fuel economy by measuring the distance on multiple tankfuls, unfortunately.)

Subaru says the hybrid Crosstrek can run solely on electric power at speeds up to 65 mph, and I confirmed that number – on flat or downhill roads under relatively modest power demand. It also quotes a 0-60 acceleration time that’s one second faster than the standard Crosstrek, though it doesn’t give actual numbers. The electric motors definitely gave the hybrid a bit of extra pep compared to the conventional model, which borders on slow.

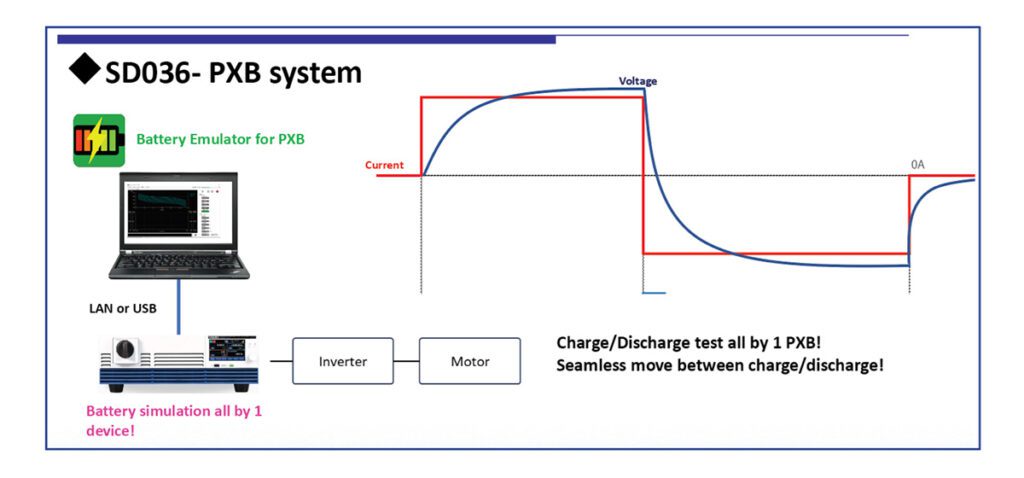

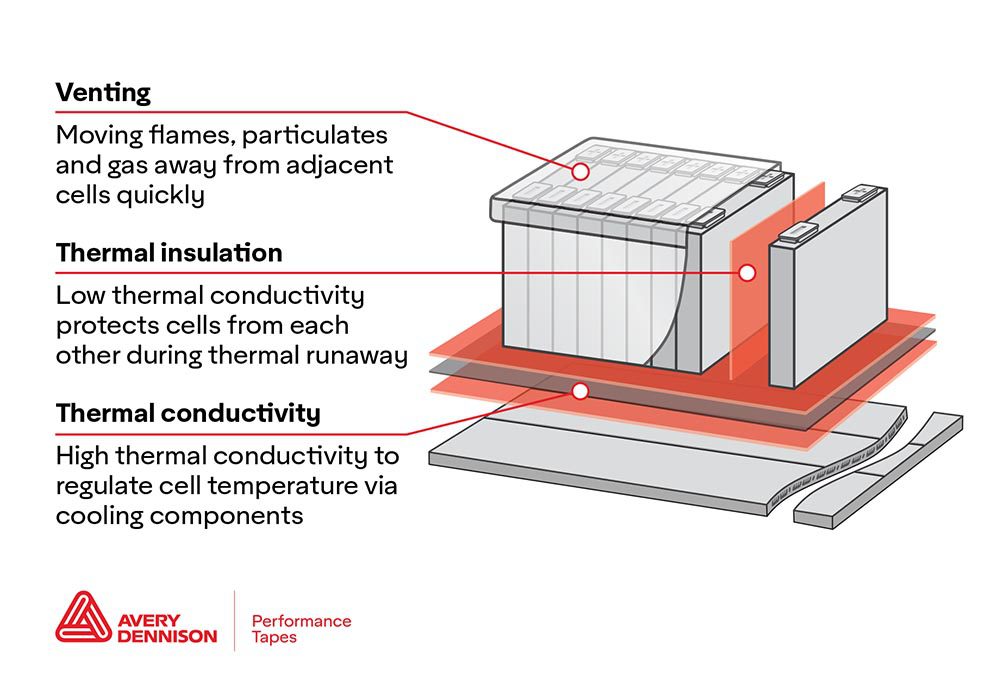

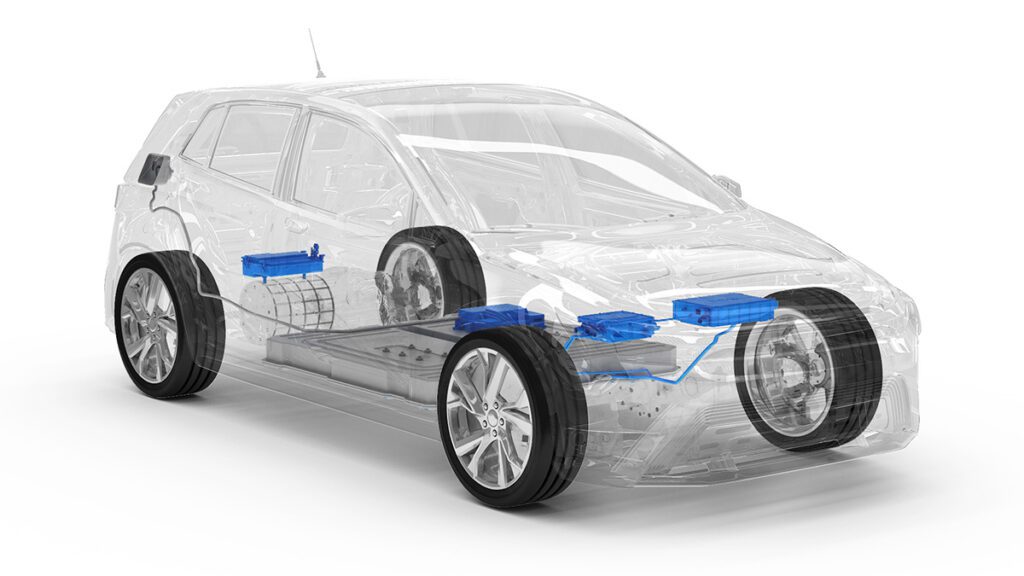

Subaru also gets points for smoothness and good blending of regenerative and friction braking. The smoothness is helped by the use of Toyota’s two-motor system, as opposed to the single-motor systems used in plug-in hybrids from Hyundai, Kia, Volkswagen and others.

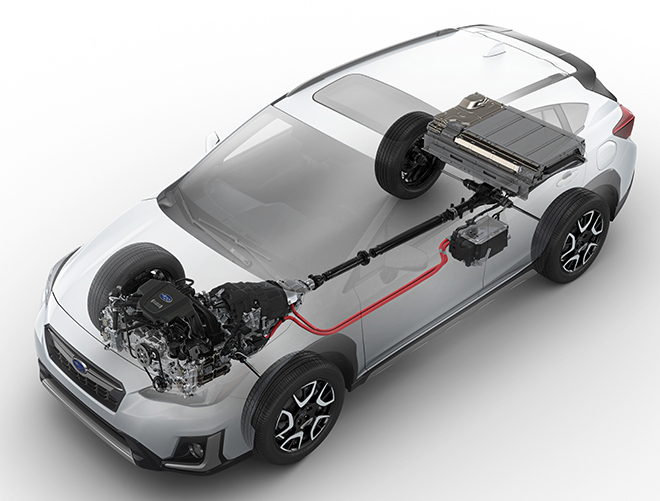

Finally, as a strong hybrid, I found it easy to keep the car accelerating on electric power alone. It’s not hugely fast, but neither is the Prius Prime whose battery and power electronics it shares. The Subaru, incidentally, doesn’t use the two-motor hybrid system from the Prius Prime, contrary to some reporting. Instead it uses the more powerful system from the Camry Hybrid. That was necessary to move a car that’s 500 pounds heavier than the standard Crosstrek, per Garrick Goh, Subaru’s US Car Line Planning Manager for Electrified Vehicles.

The cons

The Crosstrek Hybrid proved frustrating in a few ways, however. Unlike the Prius Prime, it’s not programmed to run entirely on battery power until its electric range is exhausted. Accelerate hard onto a highway, and the engine kicks on and stays on for a couple of minutes until the catalytic converter has warmed up.

To be fair, that’s not terribly surprising. The Prius Prime was optimized for efficiency, with a much sleeker shape and lighter weight. The hybrid Crosstrek is an adaptation of an existing vehicle, retrofitted to meet California state regulations that require sales of set volumes of vehicles that have some zero-emission capability. It weighs more than 3,700 pounds, compared to the Prime’s 3,350 pounds.

The Subaru also suffers from a noisy engine, an area in which the Prius Prime was vastly improved over its predecessor. Partly that’s because the flat-four engine note is more distinctive, but it’s also due to the fact that the engine has been retuned for maximum efficiency at higher speeds, with the battery providing the low to medium power the conventional car’s engine had to offer as well.

When more power was needed, the result was thrashy and loud engine noise from under the hood, along with quite a lot of “motorboating,” or the experience of engine noise and road speed being entirely disconnected. Subaru’s conventional continuously variable transmissions (CVTs) have been tuned superbly to eliminate that sensation, so it was jarring to feel it return as if the car were an older Prius.

There was also a remarkable amount of whine from the electronics, especially on deceleration, a problem I noticed Toyota has all but eliminated in the Prius Prime. Goh suggested that the majority of this was the car’s pedestrian-alert feature, which he likened to the whine of a 1960s flying saucer in a movie.

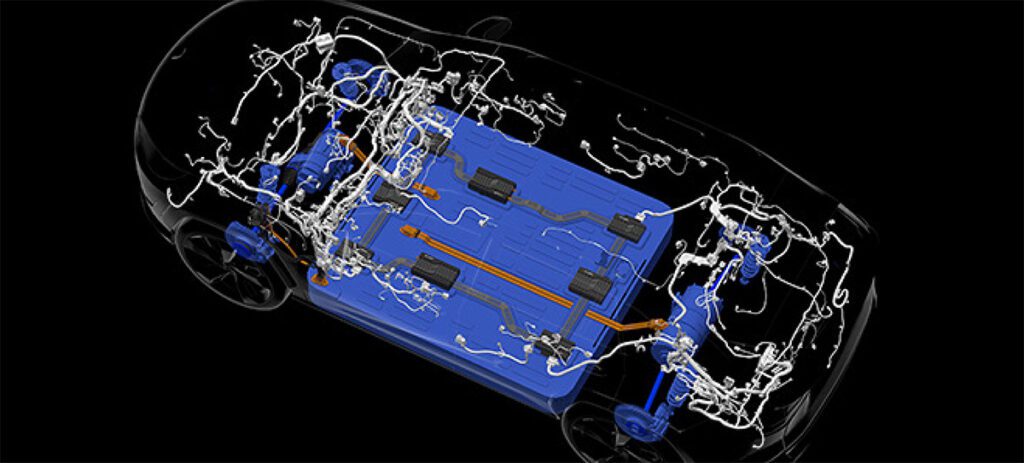

Finally, the need to retrofit a largish battery pack into the Crosstrek while retaining mechanical all-wheel drive meant it couldn’t go under the rear seat as it does in the Prius Prime – which does not offer AWD. Instead, the battery sits under a considerably higher load deck, cutting into cargo volume in the same way it did in the (now discontinued) Ford C-Max Energi PHEV. A conventional Crosstrek has 55.3 cubic feet of cargo volume with the seat folded, and 20.8 cu ft with the rear seat up, and still has room for a space-saver spare. The hybrid has 22 percent less, at 43.1 cu ft (or 15.9 cu ft with the rear seat up), and no spare tire at all.

Did the Subaru live up to its rated 17-mile range? More or less; I got 15 miles each of two times I charged to full and then ran the battery to empty. That’s within the 10-to-12-percent margin I give hybrids on ratings. Temperature played a role too: Unlike mostly temperate California, my upstate New York location saw temperatures that likely dipped below 40° F at night, and rose only into the low 50s at the warmest part of the day.

How did we get here?

I suspect Subaru is at best lukewarm about the prospect of building cars powered partly or in full by battery packs. The company had a small program 10 years ago that resulted in sales of about 400 Stella EVs, but that ended in 2011 after the minicar with a 9 kWh battery pack languished in the market.

The powerful California Air Resources Board, however, has extended its ZEV sales mandate from the six largest makers to what it dubs mid-size manufacturers, including Jaguar Land Rover, Mazda, Subaru, Volkswagen, Volvo and others. Of those, Subaru and Mazda are the smallest non-luxury brands.

Globally, Subaru sells only a bit more than one million vehicles a year, a total just one-tenth that of GM, Toyota, Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi, or the VW Group. So it has to spend its limited capital funds carefully and wisely. Over five years, it has completely redesigned its engine and launched a new vehicle architecture that underpins everything from the Impreza/Crosstrek compacts to the Ascent seven-seat crossover utility.

That means that electric cars have been a distant second priority for the small company. It turned to Toyota for the electrical components, integrated into a car that kept its flat-four “boxer” engine and all-wheel drive. That’s the car I drove.

As for the company’s future all-electric cars, we know considerably less. Subaru could turn to Toyota for the platform it will launch, reluctantly, in 2020. That’s what Mazda will do, for instance. But Subaru’s then-CEO Yasunuki Yoshinaga said in 2017 that the company planned to offer one or more existing models in fully electric versions, contrary to Mazda’s likely plans for a new model name affixed to its first all-electric production car.

In the end, if you want a more fuel-efficient Subaru Crosstrek that works well (if noisily) as a conventional hybrid, this is your only choice – and a good one. If you want a Subaru that plugs in, it’s also your only choice. In either case, it’s a Subaru first and offers those qualities second, which will reassure loyal owners – of which the brand has a lot.

Those dedicated owners who want the car, however, may have to work hard to get it. The company hasn’t commented on projected sales volume, but I strongly expect that it will sell only the number of units required to meet CARB ZEV regulations, and only in those states that follow California’s emission rules.

That means California and Oregon first, with the rest of the California-rules states to follow. Subaru says every dealer in those states will have inventory of the hybrid, but like several other electric and plug-in hybrid cars, it will not be made available outside those areas. Dealerships in other states will not be offered the Crosstrek Hybrid.

In those states, repairs to the car’s unique electrical and electronic components may take an extra day for the company to bring in a regional Field Service person who’s been trained on those components. (Regular servicing, which doesn’t include those components, can be accomplished at any Subaru dealer.)

All things considered, I ended up liking the Crosstrek Hybrid. It’s a Subaru first and foremost, it’s fuel-efficient, and if you regularly plug it in, you can cover notable amounts of electric miles when your travels include shorter trips and lower speeds. Did I mention I tend to be partial to Subarus?

The company says initial demand has been higher than it expected, but it’s still considering what sustained sales might look like. As of now, the plug-in hybrid Crosstrek is sold only in parts of the US, with plans for Canada now being developed.

The 2019 Subaru Crosstrek Hybrid I tested had a sticker total of $38,470, composed of the $34,995 base price; a $2,500 option package that bundled the power moonroof, heated steering wheel, navigation system, and HD audio; and a mandatory $975 destination and delivery fee. It is eligible for a $4,500 federal income tax credit and a $1,500 California purchase rebate, among other incentives.

This article appeared in Charged Issue 41 – January/February 2019 – Subscribe now.